A Killer Golf Swing Is a Hot Job Skill Now

Companies are eager to hire strong players who use hybrid work schedules to schmooze clients on the course

Standout golfers who aren’t quite PGA Tour material now have somewhere else to play professionally: Corporate America.

People who can smash 300-yard drives and sink birdie putts are sought-after hires in finance, consulting, sales and other industries, recruiters say. In the hybrid work era, the business golf outing is back in a big way.

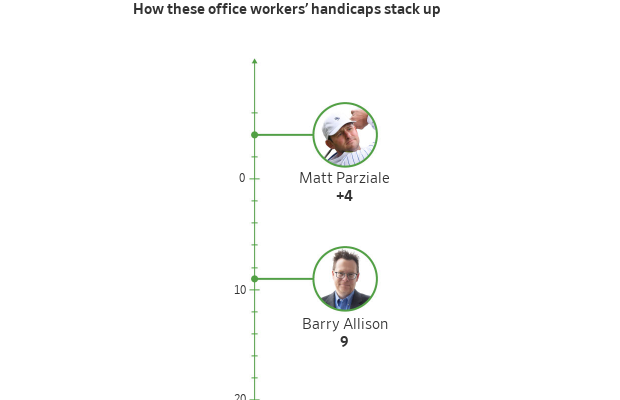

Executive recruiter Shawn Cole says he gets so many requests to find ace golfers that he records candidates’ handicaps, an index based on average number of strokes over par, in the information packets he submits to clients. Golf alone can’t get you a plum job, he says—but not playing could cost you one.

“I know a guy that literally flies around the world in a private jet loaded with French wine, and he golfs and lands hundred-million-dollar deals,” Cole says.

Tee times and networking sessions have long gone hand-in-golf-glove. Despite criticism that doing business on the course undermines diversity, equity and inclusion efforts—and the fact that golf clubs haven’t always been open to women and minorities —people who mix golf and work say the outings are one of the last reprieves from 30-minute calendar blocks

Stars like Tiger Woods and Michelle Wie West helped expand participation in the sport. Still, just 22% of golfers are nonwhite and 26% are women, according to the National Golf Foundation.

To lure more people, clubs have relaxed rules against mobile-phone use on the course, embracing white-collar professionals who want to entertain clients on the links without disconnecting from the office. It’s no longer taboo to check email from your cart or take a quick call at the halfway turn.

With so much other business conducted virtually, shaking hands on the green and schmoozing over clubhouse beers is now seen as making an extra effort, not slacking off.

Americans played a record 531 million rounds last year. Weekday play has nearly doubled since 2019, with much of the action during business hours , according to research by Stanford University economist Nicholas Bloom .

“It would’ve been scandalous in 2019 to be having multiple meetings a week on the golf course,” Bloom says. “In 2024, if you’re producing results, no one’s going to see anything wrong with it.”

A financial adviser at a major Wall Street bank who competes on the amateur circuit told me he completes 90% of his tasks by 10 a.m. because he manages long-term investment plans that change infrequently. The rest of his workday often involves golfing with clients and prospects. He’s a member of a private club with a multiyear waiting list, and people jump at the chance to join him on a course they normally can’t access.

There is an art to bringing in business this way. He never initiates shoptalk, telling his playing partners the round is about having fun and getting to know each other. They can’t resist asking about investment strategies by the back nine, he says.

Work hard, play hard

Matt Parziale golfed professionally on minor-league tours for several years, but when his dream of making the big time ended, he had to get a regular job. He became a firefighter, like his dad.

A few years later he won one of the biggest amateur tournaments in the country, earning spots in the 2018 Masters and U.S. Open, where he tied for first among non-pros.

The brush with celebrity brought introductions to business types that Parziale, 35 years old, says he wouldn’t have met otherwise. One connection led to a job with a large insurance broker. In 2022 he jumped to Deland, Gibson Insurance Associates in Wellesley, Mass., which recognised his golf game as a tool to help win large accounts.

He rescheduled our interview because he was hosting clients at a private club on Cape Cod, and squeezed me in the next morning, before teeing off with a business group in Newport, R.I.

A short time ago, Parziale couldn’t imagine making a living this way. Now he’s the norm in elite amateur golf circles.

“I look around at the guys at the events I play, and they all have these jobs ,” he says.

His boss, Chief Executive Chip Gibson, says Parziale is good at bringing in business because he puts as much effort into building relationships as honing his game. A golf outing is merely an opportunity to build trust that can eventually lead to a deal, and it’s a misconception that people who golf during work hours don’t work hard, he says.

Barry Allison’s single-digit handicap is an asset in his role as a management consultant at Accenture , where he specialises in travel and hospitality. He splits time between Washington, D.C., and The Villages, Fla., a golf mecca that boasts more than 50 courses.

It can be hard to get to know people in distributed work environments, he says. Go golfing and you’ll learn a lot about someone’s temperament—especially after a bad shot.

“If you see a guy snap a club over his knee, you don’t know what he’s going to snap next,” Allison says.

Special access

On a recent afternoon I was a lunch guest at Brae Burn Country Club, a private enclave outside Boston that was the site of U.S. Golf Association championships won by legends like Walter Hagen and Bobby Jones. I parked in the second lot because the first one was full—on a Wednesday.

My host was Cullen Onstott, managing director of the Onstott Group executive search firm and a former collegiate golfer at Fairfield University. He explained one reason companies prize excellent golfers is they can put well-practiced swings on autopilot and devote most of their attention to chitchat.

It’s hard to talk with potential customers about their needs and interests when you’re hunting for errant shots in the woods. It’s also challenging if you show off.

The first hole at Brae Burn is a 318-yard par 4 that slopes down, enabling big hitters like Onstott to reach the putting green in a single stroke. But to stay close to his playing partners and keep the conversation flowing, he sometimes hits a shorter shot.

Having an “in” at an exclusive club can make you a catch. Bo Burch, an executive recruiter in North Carolina, says clubs in his region tend to attract members according to their business sectors. One might be chock-full of real-estate investors while another has potential buyers of industrial manufacturing equipment.

Burch looks for candidates who are members of clubs that align with his clients’ industries, though he stresses that business acumen comes first when filling positions.

Tami McQueen, a former Division I tennis player and current chief marketing officer at Atlanta investment firm BIP Capital, signed up for private golf lessons this year. She had noticed colleagues were wearing polos with course logos and bringing their clubs to work. She wanted in.

McQueen joined business associates on the golf course for the first time in March at the PGA National Resort in Palm Beach Gardens, Fla. She has lowered her handicap to a respectable 26 and says her new skill lends a professional edge.

“To be able to say, ‘I can play with you and we can have those business meetings on the course’ definitely opens a lot more doors,” she says.

Copyright 2020, Dow Jones & Company, Inc. All Rights Reserved Worldwide. LEARN MORE

Copyright 2020, Dow Jones & Company, Inc. All Rights Reserved Worldwide. LEARN MORE

A divide has opened in the tech job market between those with artificial-intelligence skills and everyone else.

A 30-metre masterpiece unveiled in Monaco brings Lamborghini’s supercar drama to the high seas, powered by 7,600 horsepower and unmistakable Italian design.

A divide has opened in the tech job market between those with artificial-intelligence skills and everyone else.

There has rarely, if ever, been so much tech talent available in the job market. Yet many tech companies say good help is hard to find.

What gives?

U.S. colleges more than doubled the number of computer-science degrees awarded from 2013 to 2022, according to federal data. Then came round after round of layoffs at Google, Meta, Amazon, and others.

The Bureau of Labor Statistics predicts businesses will employ 6% fewer computer programmers in 2034 than they did last year.

All of this should, in theory, mean there is an ample supply of eager, capable engineers ready for hire.

But in their feverish pursuit of artificial-intelligence supremacy, employers say there aren’t enough people with the most in-demand skills. The few perceived as AI savants can command multimillion-dollar pay packages. On a second tier of AI savvy, workers can rake in close to $1 million a year .

Landing a job is tough for most everyone else.

Frustrated job seekers contend businesses could expand the AI talent pipeline with a little imagination. The argument is companies should accept that relatively few people have AI-specific experience because the technology is so new. They ought to focus on identifying candidates with transferable skills and let those people learn on the job.

Often, though, companies seem to hold out for dream candidates with deep backgrounds in machine learning. Many AI-related roles go unfilled for weeks or months—or get taken off job boards only to be reposted soon after.

Playing a different game

It is difficult to define what makes an AI all-star, but I’m sorry to report that it’s probably not whatever you’re doing.

Maybe you’re learning how to work more efficiently with the aid of ChatGPT and its robotic brethren. Perhaps you’re taking one of those innumerable AI certificate courses.

You might as well be playing pickup basketball at your local YMCA in hopes of being signed by the Los Angeles Lakers. The AI minds that companies truly covet are almost as rare as professional athletes.

“We’re talking about hundreds of people in the world, at the most,” says Cristóbal Valenzuela, chief executive of Runway, which makes AI image and video tools.

He describes it like this: Picture an AI model as a machine with 1,000 dials. The goal is to train the machine to detect patterns and predict outcomes. To do this, you have to feed it reams of data and know which dials to adjust—and by how much.

The universe of people with the right touch is confined to those with uncanny intuition, genius-level smarts or the foresight (possibly luck) to go into AI many years ago, before it was all the rage.

As a venture-backed startup with about 120 employees, Runway doesn’t necessarily vie with Silicon Valley giants for the AI job market’s version of LeBron James. But when I spoke with Valenzuela recently, his company was advertising base salaries of up to $440,000 for an engineering manager and $490,000 for a director of machine learning.

A job listing like one of these might attract 2,000 applicants in a week, Valenzuela says, and there is a decent chance he won’t pick any of them. A lot of people who claim to be AI literate merely produce “workslop”—generic, low-quality material. He spends a lot of time reading academic journals and browsing GitHub portfolios, and recruiting people whose work impresses him.

In addition to an uncommon skill set, companies trying to win in the hypercompetitive AI arena are scouting for commitment bordering on fanaticism .

Daniel Park is seeking three new members for his nine-person startup. He says he will wait a year or longer if that’s what it takes to fill roles with advertised base salaries of up to $500,000.

He’s looking for “prodigies” willing to work seven days a week. Much of the team lives together in a six-bedroom house in San Francisco.

If this sounds like a lonely existence, Park’s team members may be able to solve their own problem. His company, Pickle, aims to develop personalised AI companions akin to Tony Stark’s Jarvis in “Iron Man.”

Overlooked

James Strawn wasn’t an AI early adopter, and the father of two teenagers doesn’t want to sacrifice his personal life for a job. He is beginning to wonder whether there is still a place for people like him in the tech sector.

He was laid off over the summer after 25 years at Adobe , where he was a senior software quality-assurance engineer. Strawn, 55, started as a contractor and recalls his hiring as a leap of faith by the company.

He had been an artist and graphic designer. The managers who interviewed him figured he could use that background to help make Illustrator and other Adobe software more user-friendly.

Looking for work now, he doesn’t see the same willingness by companies to take a chance on someone whose résumé isn’t a perfect match to the job description. He’s had one interview since his layoff.

“I always thought my years of experience at a high-profile company would at least be enough to get me interviews where I could explain how I could contribute,” says Strawn, who is taking foundational AI courses. “It’s just not like that.”

The trouble for people starting out in AI—whether recent grads or job switchers like Strawn—is that companies see them as a dime a dozen.

“There’s this AI arms race, and the fact of the matter is entry-level people aren’t going to help you win it,” says Matt Massucci, CEO of the tech recruiting firm Hirewell. “There’s this concept of the 10x engineer—the one engineer who can do the work of 10. That’s what companies are really leaning into and paying for.”

He adds that companies can automate some low-level engineering tasks, which frees up more money to throw at high-end talent.

It’s a dynamic that creates a few handsomely paid haves and a lot more have-nots.

Once a sleepy surf town, Noosa has become Australia’s prestige property hotspot, where multi-million dollar knockdowns, architectural showpieces and record-setting sales are the new normal.

Now complete, Ophora at Tallawong offers luxury finishes, 10-year defect insurance and standout value from $475,000.