As Generation X Approaches Retirement, Reality Still Bites

The ‘forgotten generation,’ born between 1965 and 1980, launched their careers at the start of a massive shift in how Americans work.

The oldest members of Gen X are turning 60 next year. Many can’t afford to stop working any time soon.

Born between 1965 and 1980, Gen Xers launched their careers at the start of a massive shift in how Americans work. Companies moved from pensions that promise steady income after years of service, to plans such as 401(k)s that place employees’ retirement destiny in their own hands.

Some Gen Xers were hit hard in their prime working years during the 2008 financial crisis. Others are still paying off student debt. Their children are increasingly living at home well into adulthood, while their own aging parents often require care. Few believe they can rely on Social Security to make ends meet later in life.

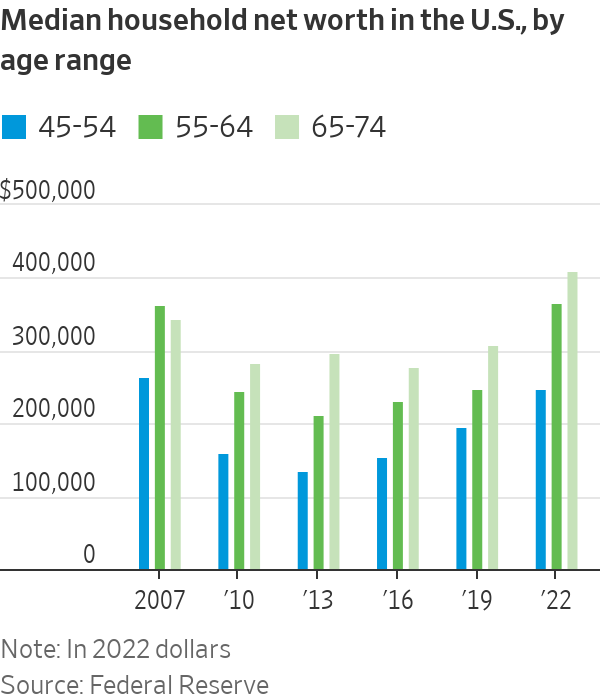

By some measures, Gen Xers are worse off financially than their baby boomer predecessors. The median household net worth of Gen Xers between 45 and 54 years old was about $250,000 in 2022, about 7% lower than that of baby boomers at the same age in 2007, according to inflation-adjusted Federal Reserve data. That was the only age group that experienced a drop in median wealth over the 15-year period.

David Bryan, 55, earns about $35,000 a year as a school-bus driver and lives on Tybee Island, Ga. He doesn’t own property and has about $100,000 in retirement savings from his previous jobs as a railroad conductor and a researcher at a college foundation.

It’s a different life than that of his parents, who worked for decades for the sheriff’s department and the post office and received steady pension checks when they retired.

“As long as my body will let me, it’s better I keep working,” said Bryan.

The roughly 65 million Americans in Gen X are sometimes referred to as the “forgotten generation,” sandwiched between the larger and louder baby boomer and millennial generations. They are also called the “latchkey generation,” often coming home from school as children to an empty house. Goldman Sachs Asset Management in a recent report called Gen X the “‘401(k) experiment’ generation.”

For decades, employers often supported loyal workers in old age through traditional pensions with set payouts for life. The advent of the 401(k) system pushed the responsibility on to the individual—and Gen X was caught squarely in the transition.

“Gen X is the first generation where they were mostly expected to figure out their retirement on their own,” said Jeremy Horpedahl , an economics professor at the University of Central Arkansas and director of the Arkansas Center for Research in Economics.

The early champions of the 401(k) never thought that it would become the dominant way most Americans save for retirement. It is named for a line in the tax code changed in 1978 that gave executives a tax-free way to defer compensation from bonuses or stock options. Human-resources executives and economists jumped on the 401(k) as a way to encourage saving for rank-and-file employees.

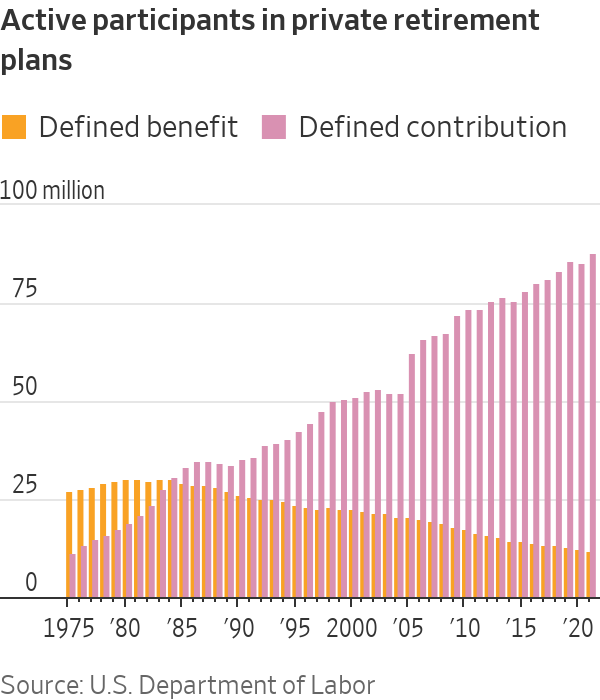

By the mid-1980s, the number of active participants in defined-contribution retirement plans—such as 401(k)s—overtook those in defined-benefit plans—such as traditional pension plans—in the private sector. Now, private pensions are rare.

When Gen Xers entered the workforce, the 401(k) was a new concept. Features such as automatically enrolling employees in a workplace plan and automatically increasing contributions every year didn’t become commonplace until later.

Other common private retirement savings tools were also introduced in the last half-century. The individual retirement account—a tax-deferred investment vehicle—was authorised in 1974, while the Roth IRA—funded with posttax money, but tax-free when withdrawn—was established in 1997.

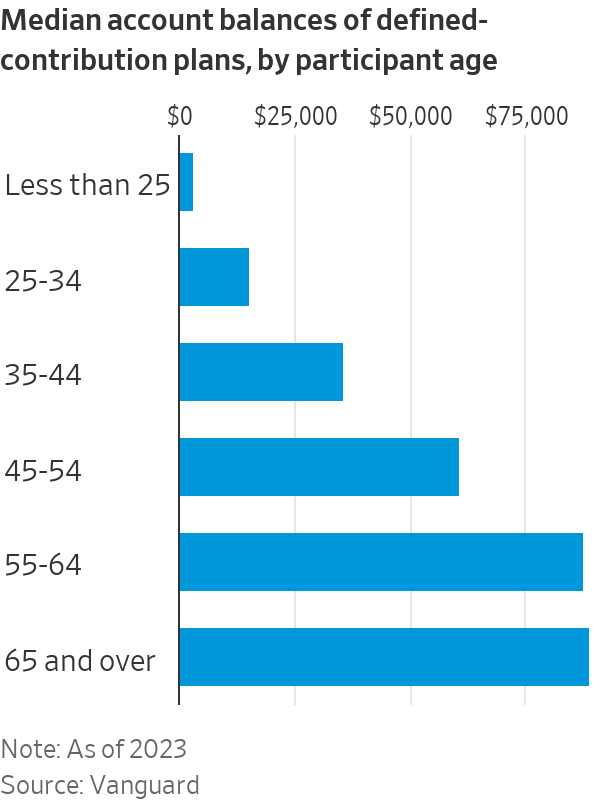

Gen Xers between 45 and 54 years old had a median account balance of roughly $60,000 in defined-contribution retirement plans at Vanguard Group in 2023, according to the firm. For most Americans, that is well below the target some financial experts recommend of having roughly six times one’s salary saved for retirement by age 50.

John Kotrides, a 54-year-old living near Charlotte, N.C., had contributed to 401(k)s ever since he started his career in banking about three decades ago. But whenever he moved to a different employer, he usually cashed out his 401(k) because there was a more urgent expense, such as a home repair or moving costs.

Keeping the money invested in the stock market didn’t seem worth it after witnessing crashes like the bursting of the dot-com bubble. Retirement seemed far away.

“You no longer have a generation of people whose employer took you from your first job into your retirement,” he said. “When we were offered 401(k)s, I don’t think that was a great deal.”

Kotrides says he doesn’t have much in retirement assets, besides the home he owns, where he lives with his wife and two daughters, who are 12 and 20 years old. After quitting his job as a mortgage lender during the pandemic, he now works as a bartender part-time and earns most of his money making social-media content, mostly nostalgic videos about the 1970s through 1990s. He likes having more time to spend with his family.

“This is basically my retirement plan,” he said. “I truly assume that I’ll continue to work to provide for my family as long as I need to.”

Even those who have benefited from the 401(k) system say it hasn’t been easy.

Scott Zibel, a 56-year-old in Leominster, Mass., started putting money in a 401(k) when he began working at a grocery store at 15. His father encouraged him to contribute. The account grew as he continued working at the store through college and became a manager. In his early 30s, he became an English teacher and expects to receive a pension after retiring.

When the stock market crashed in 2020 at the onset of the Covid pandemic, he and his wife pulled the money in his wife’s 401(k) out of the market and into a money-market fund. Now they have reinvested the money, but put a greater portion of it into bonds than before.

“I’m grateful for the 401(k), but there’s no guarantees as well,” he said, estimating his household retirement savings at a little over $1 million.

Zibel feels prepared for retirement but says he has to live frugally to save. He has driven the same car for 12 years and has avoided pricey expenses such as new carpeting for his 30-year-old home.

“My wife and I have done so much planning for the future with our money, it’s made living in the now difficult,” he said.

For some Gen Xers, the 2008 financial crisis was a hit that took years to recover from.

Around 2007, Darling “Diva” Moore was at the peak of her career as a managing partner at a title company in West Palm Beach, Fla. Then the housing market collapsed and her company went under. She couldn’t make rent on her apartment and had to crash with her significant other at the time, sometimes turning to sleeping on the beach or in the car.

“The Great Recession changed everything for us,” said Moore, who is 57. “After that, I don’t know how many Gen Xers trusted that system.”

After settling in Denver, more than two years went by before she landed a new job. She went back to school, getting an online bachelor’s degree in business management and master’s degree in human relations and organisation development. Now she is self-employed as a career counsellor.

As she is approaching her 60s, Moore is trying to locate money she contributed to various 401(k)s from jobs earlier in her career. Whenever she switched jobs, she didn’t rollover her balance to an IRA or new 401(k), so those accounts are scattered across plan providers. “In the ‘90s, they didn’t make it easy to find out where that money is,” she said.

She is also contending with student debt from a for-profit associates-degree program she completed in her 20s that has swelled to nearly $90,000 from around $27,000 due to interest.

More than a quarter of U.S. households led by Gen Xers between the ages of 45 and 54 had education loans in 2022, compared with about 15% of baby boomers at the same age in 2007, according to Fed data.

Soaring tuition costs, sky-high rents and other inflationary pressures for Gen Z are also Gen X’s problem. Many Gen Xers have forked over tens of thousands of dollars for their children to attend college. Young people are also increasingly living with parents, or relying on them for financial support, well into adulthood .

Pamela Likos’s 21-year-old son lives at home with her in the suburbs of Madison, Wis., while another son and daughter are at college.

“My kids are still definitely not grown and flown,” Likos said.

Some Gen Xers are simultaneously caring for aging parents, who are living longer than previous generations.

Likos isn’t in that situation yet, but her stepmother, who has Alzheimer’s, and her father are in their 80s.

“I need my parents to hang on healthwise for another five to 10 years because we are not ready to help financially, really,” she said.

Likos, who is 54, was the first person in her family to go to college, but didn’t work for about two decades after she got married and became a stay-at-home mom. When she got divorced about seven years ago, she found herself with no savings of her own and no resume to apply for jobs. She got a license to work as an esthetician for a few years and now is remarried. From her divorce, Likos received about half of her ex-husband’s 401(k), which comprises most of her plan for retirement.

The youngest members of Gen X are in their mid-40s, offering more time to boost savings ahead of retirement. Tyler Bond, the research director at the National Institute on Retirement Security, wonders if there will be diverging retirement experiences between the older and younger ends of the cohort.

“The older Gen Xers simply may not have time,” he said.

Avery Nesbitt, a 44-year-old operations manager in the Atlanta area, isn’t waiting for retirement to go on nice vacations or buy a new car because he wants to enjoy them now—and he doesn’t expect to be able to save up a cushy nest egg for later in life. If the Covid pandemic taught him anything, it was that anything can happen.

He and his wife have contributed modestly to employer-sponsored retirement accounts but didn’t feel like they could afford to save more. They own a home, where they live with their two children. That makes up the bulk of their wealth. He said he has put more money into life-insurance policies than in retirement accounts.

“I fully expect to work until I die,” Nesbitt said. “It is what it is.”

Copyright 2020, Dow Jones & Company, Inc. All Rights Reserved Worldwide. LEARN MORE

Copyright 2020, Dow Jones & Company, Inc. All Rights Reserved Worldwide. LEARN MORE

A divide has opened in the tech job market between those with artificial-intelligence skills and everyone else.

A 30-metre masterpiece unveiled in Monaco brings Lamborghini’s supercar drama to the high seas, powered by 7,600 horsepower and unmistakable Italian design.

A divide has opened in the tech job market between those with artificial-intelligence skills and everyone else.

There has rarely, if ever, been so much tech talent available in the job market. Yet many tech companies say good help is hard to find.

What gives?

U.S. colleges more than doubled the number of computer-science degrees awarded from 2013 to 2022, according to federal data. Then came round after round of layoffs at Google, Meta, Amazon, and others.

The Bureau of Labor Statistics predicts businesses will employ 6% fewer computer programmers in 2034 than they did last year.

All of this should, in theory, mean there is an ample supply of eager, capable engineers ready for hire.

But in their feverish pursuit of artificial-intelligence supremacy, employers say there aren’t enough people with the most in-demand skills. The few perceived as AI savants can command multimillion-dollar pay packages. On a second tier of AI savvy, workers can rake in close to $1 million a year .

Landing a job is tough for most everyone else.

Frustrated job seekers contend businesses could expand the AI talent pipeline with a little imagination. The argument is companies should accept that relatively few people have AI-specific experience because the technology is so new. They ought to focus on identifying candidates with transferable skills and let those people learn on the job.

Often, though, companies seem to hold out for dream candidates with deep backgrounds in machine learning. Many AI-related roles go unfilled for weeks or months—or get taken off job boards only to be reposted soon after.

Playing a different game

It is difficult to define what makes an AI all-star, but I’m sorry to report that it’s probably not whatever you’re doing.

Maybe you’re learning how to work more efficiently with the aid of ChatGPT and its robotic brethren. Perhaps you’re taking one of those innumerable AI certificate courses.

You might as well be playing pickup basketball at your local YMCA in hopes of being signed by the Los Angeles Lakers. The AI minds that companies truly covet are almost as rare as professional athletes.

“We’re talking about hundreds of people in the world, at the most,” says Cristóbal Valenzuela, chief executive of Runway, which makes AI image and video tools.

He describes it like this: Picture an AI model as a machine with 1,000 dials. The goal is to train the machine to detect patterns and predict outcomes. To do this, you have to feed it reams of data and know which dials to adjust—and by how much.

The universe of people with the right touch is confined to those with uncanny intuition, genius-level smarts or the foresight (possibly luck) to go into AI many years ago, before it was all the rage.

As a venture-backed startup with about 120 employees, Runway doesn’t necessarily vie with Silicon Valley giants for the AI job market’s version of LeBron James. But when I spoke with Valenzuela recently, his company was advertising base salaries of up to $440,000 for an engineering manager and $490,000 for a director of machine learning.

A job listing like one of these might attract 2,000 applicants in a week, Valenzuela says, and there is a decent chance he won’t pick any of them. A lot of people who claim to be AI literate merely produce “workslop”—generic, low-quality material. He spends a lot of time reading academic journals and browsing GitHub portfolios, and recruiting people whose work impresses him.

In addition to an uncommon skill set, companies trying to win in the hypercompetitive AI arena are scouting for commitment bordering on fanaticism .

Daniel Park is seeking three new members for his nine-person startup. He says he will wait a year or longer if that’s what it takes to fill roles with advertised base salaries of up to $500,000.

He’s looking for “prodigies” willing to work seven days a week. Much of the team lives together in a six-bedroom house in San Francisco.

If this sounds like a lonely existence, Park’s team members may be able to solve their own problem. His company, Pickle, aims to develop personalised AI companions akin to Tony Stark’s Jarvis in “Iron Man.”

Overlooked

James Strawn wasn’t an AI early adopter, and the father of two teenagers doesn’t want to sacrifice his personal life for a job. He is beginning to wonder whether there is still a place for people like him in the tech sector.

He was laid off over the summer after 25 years at Adobe , where he was a senior software quality-assurance engineer. Strawn, 55, started as a contractor and recalls his hiring as a leap of faith by the company.

He had been an artist and graphic designer. The managers who interviewed him figured he could use that background to help make Illustrator and other Adobe software more user-friendly.

Looking for work now, he doesn’t see the same willingness by companies to take a chance on someone whose résumé isn’t a perfect match to the job description. He’s had one interview since his layoff.

“I always thought my years of experience at a high-profile company would at least be enough to get me interviews where I could explain how I could contribute,” says Strawn, who is taking foundational AI courses. “It’s just not like that.”

The trouble for people starting out in AI—whether recent grads or job switchers like Strawn—is that companies see them as a dime a dozen.

“There’s this AI arms race, and the fact of the matter is entry-level people aren’t going to help you win it,” says Matt Massucci, CEO of the tech recruiting firm Hirewell. “There’s this concept of the 10x engineer—the one engineer who can do the work of 10. That’s what companies are really leaning into and paying for.”

He adds that companies can automate some low-level engineering tasks, which frees up more money to throw at high-end talent.

It’s a dynamic that creates a few handsomely paid haves and a lot more have-nots.

A bold new era for Australian luxury: MAISON de SABRÉ launches The Palais, a flagship handbag eight years in the making.

A 30-metre masterpiece unveiled in Monaco brings Lamborghini’s supercar drama to the high seas, powered by 7,600 horsepower and unmistakable Italian design.