The Crazy Economics of the World’s Most Coveted Handbag

The Hermès Birkin is one of the fashion world’s most conspicuous markers of wealth. Is it worth the investment?

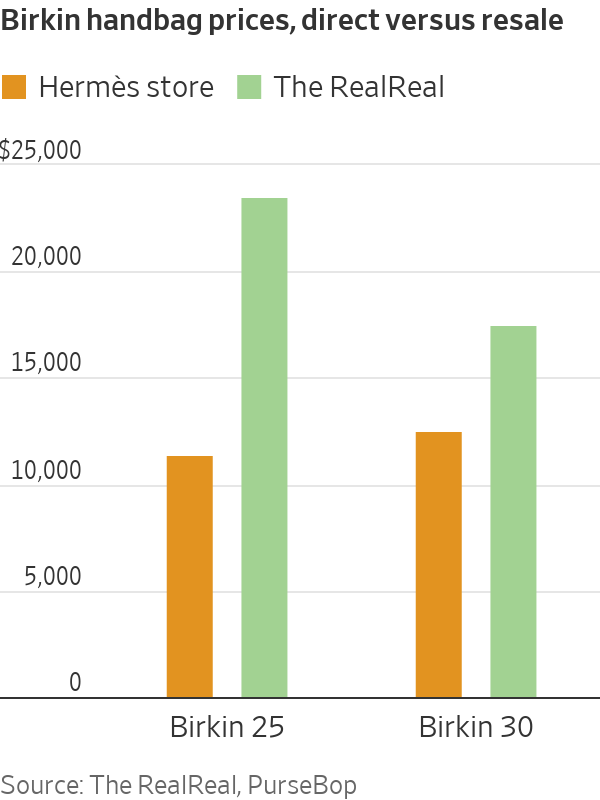

You could double your money in five minutes by buying a Birkin handbag at your local Hermès boutique and then flipping it. But getting your hands on the world’s most sought after purse is a lot more complicated than it sounds.

A basic black leather Birkin 25 costs $11,400 before tax at the Hermès store. Buyers can walk out and immediately give it to a handbag reseller like Privé Porter in exchange for $23,000 in cash. Privé Porter will then sell the Birkin on Instagram or at its Las Vegas pop-up store, possibly on the same day—box fresh, with receipt—for up to $32,000. All this for a bag that analysts estimate costs Hermès around $1,000 to make.

The unusual economics of the Birkin have upended the normal balance of power between shopper and store worker. At the Hermès boutique, it is the buyer who kowtows. Some of the wealthiest women in the world have brought homemade cookies to the store to cozy up to their sales assistant. They have offered tickets for Beyoncé concerts, trips to the Cannes Film Festival in a private jet and even envelopes stuffed with cash—all to get their hands on a Birkin.

Shoppers also spend tens of thousands of dollars on Hermès products they might not particularly want, such as an $87,500 canoe, to be in the running for a rare purse.

The Birkin turns 40 this year and is maturing into a phenomenon. To carry one is to signal that the wearer can afford to drop anywhere from $10,000 to $100,000 on a handbag. It appeals to the limelight-seeking Kardashians, who own extensive collections, but also to European Central Bank President Christine Lagarde , who is often photographed on her way to meetings carrying a Birkin.

The purse anchors the Hermès founding family’s $150 billion fortune. But they aren’t the only ones getting rich: An army of unofficial flippers all over the world profit from reselling the purse.

The Birkin first hit shelves in 1984, a couple of years after the late actress Jane Birkin and Jean-Louis Dumas, then chief executive of Hermès, met on a flight to London. After complaining that she couldn’t find the right-size handbag, the two sketched out a design together—on a drink napkin or an Air France sick bag, depending on the retelling. In return for lending her name to the new product, Hermès paid Birkin an annual royalty.

The story about the bag’s creation is part of its appeal and one of the reasons why competitors have found it hard to replicate its success. “It’s a great narrative,” said David Dubois, associate professor of marketing at the business school Insead. Shoppers like the “serendipity of the meeting” and that a woman who was admired for her style had a direct hand in its design.

The purse didn’t take off right away. During the early 1990s, shoppers could walk into an Hermès boutique and buy one off the shelf. Birkins weren’t reselling for more than their original price tag back then.

But something shifted in the years after the 2008-09 financial crisis, according to Matthew Rubinger, now chief commercial officer at the online marketplace 1stDibs and one of the first people to recognise the Birkin’s resale potential. Rock-bottom interest rates meant more money was sloshing around, and it began to find its way into alternative assets.

It also became bad taste to wear a new “it bag” every season when the economy was on the ropes. This played to the strength of no-logo designs like the Birkin. Rubinger established the handbag departments of both Heritage Auctions and Christie’s and built them into multimillion-dollar businesses. When rare Himalaya Birkins began to set records at auction, people took notice.

“Once they started getting above $100,000, things got more serious,” he said.

Today, shoppers who want a Birkin at the Hermès store must jump through hoops. First, they need to establish a good rapport with one of the brand’s sales assistants. The next step is to spend serious cash on other goods, such as silk scarves, watches and shoes, to “qualify” for a bag, according to Birkin collectors.

When a shipment of Birkins arrives at an Hermès store from France, the leather-goods manager assigns the purses to individual sales assistants, all of whom have a list of wealthy clients waiting to be offered a bag. The sales assistant must make a case for which individual on that list deserves to be offered a Birkin and get the manager’s approval.

This has created a perception among Hermès shoppers that the biggest spenders get access to Birkins first. Hermès is being sued in a California court by two wounded shoppers who allege that the brand only sells Birkins to “worthy” customers and makes purchases of the bag conditional on buying other items at the store. Hermès said in a recent court filing that it doesn’t require customers to buy other products before getting one of the coveted bags.

Just how much do shoppers need to drop to be offered a bag? Birkin collectors say that there is no hard rule but that most people can expect to shell out $10,000 or more on Hermès scarves, shoes and clothes before they will be offered a basic Birkin. To get a rare bag like the Himalaya Birkin, they might need to spend $200,000 or more.

This is known as the Hermès “prespend” or the “spend ratio” in Birkin-collecting circles. Hermès never spells this out explicitly, nor has it ever used these terms. But Birkin hopefuls say they have been told by their sales assistants that they need to visit the store more often. Resellers say that Hermès sales assistants don’t make commissions on Birkins, but that they can leverage hunger for the bag to sell other products for which they are rewarded.

Even after spending tens of thousands of dollars, Birkin hunters might not be offered the size or colour bag they want. This creates a golden opportunity for resellers.

Say a woman who shops regularly with the brand wants a red Birkin but is offered green. Rather than appearing ungrateful—because it is important to keep the sales assistant on her side in the Birkin-hunting game—she will buy the bag, knowing it can be sold to a reseller for a profit and hope to get the red later.

Hermès knows its top clients are flipping the bags. Read the fine print on a Birkin receipt, and the company asks that its customers will not, “directly or indirectly, resell Hermès products purchased in our boutiques for commercial purposes.” No Hermès shopper was willing to go on the record for this article about the experience of flipping the bags to a reseller, out of concern over being blacklisted by the brand.

The resale market has become a kind of “buy-now button” for Birkins, said Michelle Berk, founder of Privé Porter. Some shoppers are willing to pay a big premium to get their hands on a Birkin immediately, in the exact color they want. They might not have the patience for the steps needed to secure one of the bags at the Hermès store.

In the past, resellers recruited flight attendants or polished overseas students to buy Birkin bags in Hermès stores all over the world in return for a fee. Now, the flippers get most of their supply from Hermès’s VIP customers. They also get Birkins by trading with their peers on WhatsApp. If clients are looking for a size or colour that one seller doesn’t have in stock, they can put out a call on the resellers’ group chat to see if anyone has that model.

One way Birkin hunters can accelerate an in-store purchase is by splashing out on the brand’s furniture or fine jewellery, said Judy Taylor, founder of Madison Avenue Couture and a handbag reseller for 15 years.

They can pick up an $8,000 paper basket for the home office, a $70,000 gold bracelet or a $140,000 sofa. Taylor said Hermès’s sales in categories like fine jewellery or watches, where the brand isn’t known for its expertise, are at least partially driven by Birkin hunters.

“No offence to Hermès, but if you can buy a necklace from Van Cleef for the same price as Hermès, you’ll likely go to Van Cleef,” she said.

Really big spenders are offered bespoke goods. Hermès does a sideline in special-order skis, skateboards and fishing gear for superwealthy clients and can customise the interior of a yacht or chopper. Privé Porter’s Berk received a message from a customer who was offered an $87,500 canoe. These buyers get access to the rarest Birkins.

An unusually large amount of new Hermès inventory ends up for sale in the secondhand market—another sign that Birkin mania might be driving sales of products that customers don’t really want. Of all the nonhandbag Hermès items on The RealReal , 35% are in pristine condition, according to data supplied by the luxury resale website. The average for other designers on The RealReal, including Louis Vuitton, Gucci, Prada, Bottega Veneta and Saint Laurent, is 20%.

The Birkin’s popularity is very flattering for Hermès and might also help the company to keep its marketing budget low. It doesn’t need to promote itself when celebrities can be relied upon to freely splash photos of their bags on social media. In 2023, Hermès reinvested 4% of its sales back into promotions, compared with 12% at crosstown rival LVMH Moët Hennessy Louis Vuitton.

But the circus does cause problems for Hermès. Last year, the company had to fire staff at its Miami Design District store after some customers got more than their official allocation of Birkins, according to sources. Collectors say Hermès only allows two bags a year per individual, but employees might have been helping shoppers to get around this.

Shoppers and resellers have tried to bribe their way to Birkins. Hermès has strict rules about what customers can and can’t give sales assistants as gifts. Well-behaved Birkin hunters give goods that can be handed over openly at the store and shared among employees—hence the home-baked cookies. Trays of baklava are another go-to.

Hermès doesn’t like the flipping, but stamping out the resellers would harm the brand’s own interests. The company raised prices of its exotic-skin Birkins by around 20% in January. Resellers think the move was aimed at squeezing profits in the secondhand market, but it hasn’t worked. Dealers passed on the increase to their customers without a hitch.

Hermès could increase production and flood the market with new bags. This would end the financial incentive to resell Birkins, but it would also destroy their mystique.

Why are women— and increasingly men , too—so hungry for the Birkin? One justification for spending huge sums on a handbag is that the Birkin is a good investment. Except, it isn’t really. Any profit on reselling a bag purchased in store will be lower after factoring in the thousands of dollars spent on other goods to qualify.

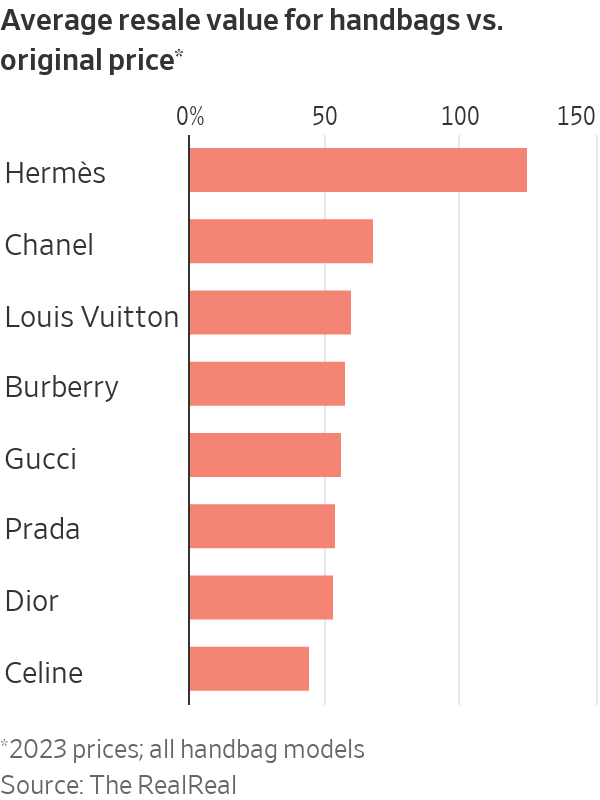

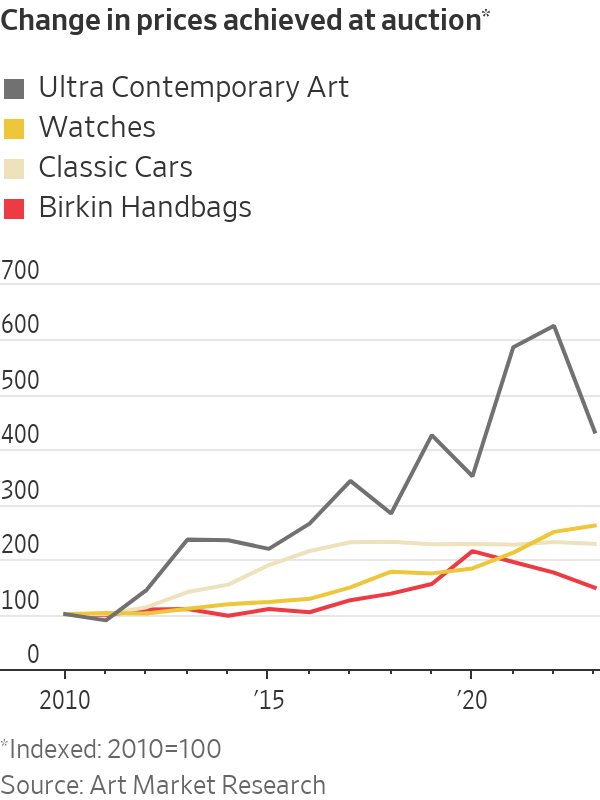

A bag sourced from a reseller or on the block at Christie’s has limited upside because a hefty markup is factored into the price. A Birkin bought at auction in 2010 would sell for around 50% more today, according to Art Market Research data. Contemporary art, watches and classic cars have all performed better. Hermès’s own stock has been a much smarter investment than the Birkin, rising more than 20-fold since 2010.

Shoppers seem to lust after the Birkin because it is rare, expensive and well made. There is no better status symbol for those who want to display their wealth. And the hunt involved in getting one might be the whole point. Wealthy shoppers tolerate waiting at the Hermès store in a way that wouldn’t be acceptable in other areas of their lives.

Even how a person treats the Birkin has turned into a kind of code. Some collectors store them in glass display cabinets, hardly ever using them. This preserves their resale value.

But the supermodel Irina Shayk was photographed last year carrying her dog in a black crocodile Birkin. According to Sasha Skoda, The RealReal’s vice president of merchandising, the subtext to the “messy Birkin” trend is that you have to be seriously rich to treat a $40,000 handbag this casually. Jane Birkin was also hard on her bags, covering them with political stickers and tying charms around the handles. One of her weathered black Birkins sold at auction for £119,000 in 2021, around $150,000 at current exchange rates.

Rival luxury brands are trying to come up with challengers. Louis Vuitton recently launched a $1 million handbag. Chanel has almost doubled the price of its classic flap purse in four years to make it more exclusive.

For now, though, the reign of the Birkin looks secure. If you want to own one, better dig deep at the Hermès store.

—Herme`s Birkin bag provided by The RealReal.

Copyright 2020, Dow Jones & Company, Inc. All Rights Reserved Worldwide. LEARN MORE

Copyright 2020, Dow Jones & Company, Inc. All Rights Reserved Worldwide. LEARN MORE

The sports-car maker delivered 279,449 cars last year, down from 310,718 in 2024.

Chinese carmaker GAC will expand its Australian electric vehicle line-up with the city-focused AION UT hatchback.

The sports-car maker delivered 279,449 cars last year, down from 310,718 in 2024.

Porsche car deliveries fell 10% in 2025 as demand was hit by a slowdown in luxury spending in China and as it ceased production of its 718 Boxster and 718 Cayman models through the year.

The German luxury sports-car maker said Friday that it delivered 279,449 cars in the year, down from 310,718 in 2024.

The company had a tumultuous year as it contended with a stuttering transition to electric vehicles and a tough Chinese market, while the Trump administration’s automotive tariffs presented a further headwind.

Deliveries in its largest sales region of North America were virtually flat at 86,229, but continued challenges in China meant deliveries in the country dropped 26% to 41,938 vehicles.

Automakers have faced intense competition in China, sparking a prolonged price war as rivals cut prices to win customers, while a lengthy property market slump and economic-growth concerns in the country has also led to buyers pulling back on luxury spending.

“Key reasons for the decline remain the challenging market conditions, particularly in the luxury segment, and the very intense competition in the Chinese market, especially for all-electric models,” the company said.

Other German brands including Audi, BMW and Mercedes-Benz have all recently reported that the challenging Chinese market hit demand last year.

In Europe, Porsche deliveries fell 13% to 66,340 cars excluding its home market of Germany, while German deliveries dropped 16%.

The company cut guidance several times last year as it warned of hits from U.S. import tariffs, investments in new combustion engines and hybrid models amid the slow uptake of EVs, and the competitive situation in China.

Porsche also last year announced plans to scale back its EV ambitions and instead expand its lineup with more gas-powered and plug-in hybrid models than it had originally planned.

However, in its statement Friday, the company said it increased its share of electrified-vehicle deliveries in the year. Around 34% of vehicles delivered worldwide were electrified, an increase of 7.4 percentage points on year, with about 22% all-electric vehicles and 12% plug-in hybrids.

That leaves its global share of fully-electric vehicles at the upper end of its target range of 20% to 22% for 2025.

In Europe, for the first time in 2025, more electrified vehicles than purely combustion engine vehicles were delivered.

The Macan topped the delivery charts in the year, while the 911 reached a record high with 51,583 deliveries worldwide, it said.

Porsche said it is investing in its three-pronged powertrain strategy and will continue to respond to increasing demand for personalization requests from customers.

“We have a clear focus for 2026,” Sales and Marketing Chief Matthias Becker said. “We want to manage supply and demand in accordance with our ‘value over volume’ strategy.

“At the same time, we are realistically planning our volume for 2026 following the end of production of the 718 and Macan with combustion engines.”

Three completed developments bring a quieter, more thoughtful style of luxury living to Mosman, Neutral Bay and Crows Nest.

The era of the gorgeous golden retriever is over. Today’s most coveted pooches have frightful faces bred to tug at our hearts.