The Five Things Keeping Us From Going All-Electric

The ‘electrification of everything’ gets talked about a lot these days. But it isn’t going to happen soon. Nor should we want it to.

Electrification is all the buzz.

As more governments, corporations, investors and consumers commit to reducing the world’s reliance on carbon-intensive fossil fuels, they are frequently turning to electricity as the power of choice. The International Renewable Energy Agency, an intergovernmental organisation, projects that close to half of world energy consumption could be in the form of electricity by 2050, up from about 20% today.

It makes sense: Electrification is often the fastest and cheapest way to decarbonise our energy consumption. The technologies to decarbonise electricity already exist and are, for the most part, readily deployable at a large scale by the private sector.

But here’s a sobering fact about all the talk of the “electrification of everything”: It isn’t likely to happen. At least, not soon. We can’t go all the way down the electrification road for a host of reasons—nor should we want to. For one thing, it would place unnecessary limitations on other viable solutions to rising greenhouse-gas emissions. It also ignores existing technical, regulatory and strategic constraints on electrification.

None of this is to say the world shouldn’t be shifting to new—and cleaner—electricity. And not just because of its role in fighting climate change. Among other things, electrification via renewable energy is playing a pivotal role in energy security for a variety of countries where oil and gas is scarce and expensive, and where volatile fuel prices threaten economic growth and fiscal stability. Clean energy helped Germany and other European countries cope with the loss of natural-gas imports from Russia last year. New clean energy is also helping key economies like China and India reduce air pollution.

But even with its environmental and strategic benefits, electrification won’t be the be-all and end-all for the foreseeable future.

Here are five reasons why:

1. Some things can’t be electrified

There are a lot of industries that are too difficult or expensive to be electrified for the foreseeable future. Do you want to know why there is no major commercial airline currently operating electric long-distance flights? It’s because the battery weight needed to hold enough energy for a trans-Atlantic flight would be greater than that of the airliner itself.

The weight of the battery and driving range is also a barrier for electrifying 18-wheeler trucks, though that electrification technology is further along than that for large jets. Freightliner has a big rig called eCascadia, but its range is only 250 miles, recharging takes over 90 minutes, and the e-truck is two to three times more expensive than its diesel-fuel version.

That may change as the battery and charging-station technology develops. A new study by the Environmental Defense Fund says that long-distance battery electric trucks could be cost effective by 2030, but other solutions are also possible by then, such as hydrogen, waste-to-energy, biofuels and tailpipe capture. (More on that in a moment.)

High-heat industrial processes, such as those for blast furnaces, cement kilns and petrochemical plants, are another commercial activity that will be hard to electrify, because electric high heat can be challenging and expensive for some industrial applications.

One key problem is that any unplanned downtime or fluctuation in temperature levels—caused by electrical fluctuations or disruptions from weather, accidents or a failed circuit breaker—not only can ruin the end product but also possibly damage billions of dollars of industrial equipment. While that scenario can be averted with automated backup energy systems, as is done routinely for nuclear plants to prevent a meltdown, it’s still an expensive add-on cost.

2. Cheaper alternatives may be coming for the most difficult-to-electrify areas

Electric power doesn’t have a monopoly on innovation. As a result, it could be risky for some industries to invest in some electrical solutions at the moment, knowing there might be a superior, cheaper technical solution down the road. Alternatives such as biofuels, hydrogen or biogas and fossil fuels with carbon sequestration offer the potential to be superior sources of power.

For instance, Remora, a startup based in Wixom, Mich., is designing a device that can collect tailpipe CO2 directly while a truck is in operation, compressing it for later sequestration or sale. Several airlines have started to use jet fuel made from purified biogenic waste that can be mixed with oil-based diesel fuel—so-called drop-in fuels that don’t require special or new fuel-transport infrastructure. Hydrogen made from renewable energy also could eventually be a solution for fueling planes and trucks.

Heidelberg Materials, a global manufacturer of building materials, is studying carbon capture and storage for its Mitchell, Ind., operations that would allow it to continue to use a fossil-fuel energy source while adding equipment that would separate CO2 emissions from other waste gases before, during and/or after combustion activities. Heidelberg would then transport its waste CO2 to be permanently injected into deep geological storage or to be reused making other products in a way that it doesn’t wind up back in the atmosphere.

These examples have the advantage of using existing energy infrastructure rather than retiring it before its end-of-life service.

3. Access to land, a surfeit of complaints

Yes, there is plenty of uninhabited land in many countries, and especially in the U.S. But uninhabited doesn’t always spell accessibility.

For one thing, in highly urbanised regions or densely populated countries, it can be difficult to find sufficient empty land to support alternative-fuel installations. Around the world, in places as diverse as India and Africa, renewable-energy developers often have trouble getting permits to buy or lease the necessary acreage. And in many areas, including the U.S., local populations can object to living near wind and solar farms, or near the power transmission and distribution lines that they require.

Consider this: It would take a wind farm on about 100,000 acres to generate the same amount of electricity as a one-gigawatt nuclear plant that typically occupies less than 1 square mile, or 640 acres. Princeton University estimates in a high-renewable-energy scenario, where solar and wind would account for virtually all electricity generation for the U.S. in 2050, the number of wind turbines would require roughly 244 million acres of uninhabited land—even assuming efficiency improvements. The current U.S. electrical system only uses about 20 million acres for the power generation business, including fuel-source production (e.g., coal, natural gas, solar, wind, nuclear and hydro), and power plants. Today’s power lines take up 4.8 million acres in the U.S., but that could increase sharply the more renewables that are added.

For a small country like Japan, that renewables-footprint requirement seems insurmountable, even if its nascent offshore wind business gets off the ground. But even for a large nation like the U.S., construction of wind and solar farms often gets held up by groups who want to use the land (or sea) for something else. In the entire U.S., there are two small offshore wind platforms currently in operation, with a third, larger one, nearing completion. The Biden administration is trying to change that at the federal level, but local factors are often hard to sort out.

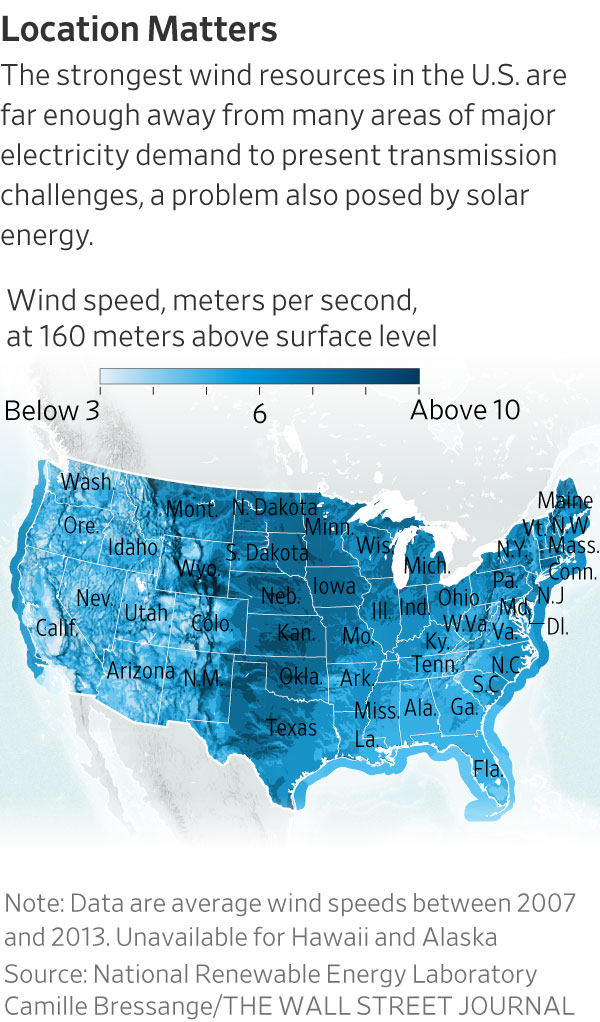

Moreover, all that uninhabited U.S. land isn’t necessarily contiguous with large energy-using metropolitan regions or located where the most commercial-scale resource of renewable energy is available. For instance, many large U.S. cities aren’t contiguous with Midwest or offshore wind resources or Southwest solar.

4. Difficulty getting the necessary permits

Since the energy resource used for electricity generation often isn’t located in populated areas, that means more transmission lines will be needed, and more lines means more permitting, which can be a time-consuming, multiyear process.

In addition to potentially requiring new transmission lines, new renewable projects also have to receive technical approval to be allowed to connect into existing grids to prove that adding more electricity won’t destabilise existing service. Again, that can take years for regulators to study and approve. The U.S. Congress has talked about permitting reform, but a solution to the problem isn’t currently on the horizon.

The U.S. isn’t the only place with transmission-construction and grid-connection obstacles. In India, land permitting for solar energy can be a bureaucratic nightmare and remains a barrier. In Germany, local opposition to new high-tension transmission lines to carry offshore wind energy from the country’s northern shores to its southern factories blocked projects for years before the Ukraine crisis. In Africa, governments that can access foreign aid for construction of wind and solar installations have had more difficulty financing the transmission lines to carry the power generated to populations and industry. All of this will continue to slow down electrification.

5. Electricity grids are highly interruptible

It isn’t just the occasional squirrel that’s the problem. In recent years, we have witnessed weather systems that knocked out power for huge swaths of the U.S. at once. The war in Ukraine is a reminder that cyberattacks against the grid could be catastrophic if too many aspects of daily life are tied to a singular infrastructure. Already, there are many vital services that cannot be conducted without access to electricity, like lighting, telecommunications, data centres and financial services. Broadening that to our entire fuel system and industrial operations seems risky, if not downright irresponsible.

There will be technical solutions to the risks of electricity disruptions, but it will take time and money to implement them. Households, governments and regional grids will all have to invest in backup systems that can be turned on seamlessly using automation when the larger grid goes down. That could take decades—and an enormous amount of money. BloombergNEF estimates that it could take as much as $17.3 trillion to expand the grid and $4.1 trillion to maintain what is there now, for a total of $21.4 trillion.

Ultimately, there is little doubt that the world is heading for the electrification of a lot more things. And that’s good—for energy security, stable economic growth and reduced greenhouse-gas emissions.

But it’s also clear that a goal of electrifying everything is neither possible nor desired, and putting all our power eggs in one basket would be a fool’s errand. Innovation is by no means isolated to the electric domain. Many forward-looking businesses are experimenting with new ways to squeeze emissions out of industrial processes, and to replace fossil fuels in transport and building applications, in some cases with assistance from governments. Power to them. Rather than naysay what’s not electricity, let’s hope they unlock superior solutions.

Copyright 2020, Dow Jones & Company, Inc. All Rights Reserved Worldwide. LEARN MORE

Copyright 2020, Dow Jones & Company, Inc. All Rights Reserved Worldwide. LEARN MORE

Formula 1 may be the world’s most glamorous sport, but for Oscar Piastri, it’s also one of the most lucrative. At just 24, Australia’s highest-paid athlete is earning more than US$40 million a year.

From gorilla encounters in Uganda to a reimagined Okavango retreat, Abercrombie & Kent elevates its African journeys with two spectacular lodge transformations.

Jeff Siegrist couldn’t take his mind off the car he sold in 1996. So he set out to track it down.

Locals in Pawleys Island have a special affection for classic vehicles. The coastal South Carolina town is home to many nostalgic retirees, and on weekends its streets see plenty of restored ‘60s-era muscle cars.

Of all the classics motoring past Parlor Doughnuts on Ocean Highway, none has captured the community’s attention like Rudolph the Red-Nosed Volkswagen.

“Everybody in town rubber necks and waves when this Beetle drives by,” says Rev. Wil Keith, a 47-year-old priest. “It’s one of the much-adored cars in our little town right now.”

It is a 1971 red Super Beetle and its story is special.

Jeff Siegrist was a student at the University of Tennessee when he first set eyes on her at a Knoxville dealership.

Siegrist pounced, handing over his father’s old Ford Falcon and $2,278.54 for the Bug. He kicked in $67.45 for an AM radio and $5.95 for a cigarette lighter.

“So that was my car from that day forward,” says Siegrist, an executive search consultant specialising in the forest products industry.

The Beetle was a sales phenomenon and a pop-culture hit that ushered in the era of mass European auto imports. It was also a Hollywood star, thanks to Herbie from the “Love Bug” movie franchise.

Siegrist road-tripped his Beetle all over. When he met his future wife, Mary, he took her on a first date in the red Bug. When the couple had their first child, the baby boy came home in the backseat.

“It was part of the family,” says Siegrist. Mary gave the car its name, around Christmas time in 1972: Rudolph.

The couple had two more children and ultimately sold the car in 1996. “It just wasn’t practical anymore,” he says. “There were tears in my eyes.”

Up to this point, the story isn’t much different from many of the more than 21.5 million original Beetles that Volkswagen sold.

But during the pandemic, things got interesting.

“I kept thinking, ‘Boy, I wish I knew where my old Beetle was,’” says Siegrist. “I wondered whether other people loved it the way my wife and I did.”

Eventually he got serious. He dug up the car’s original bill of sale, which had a vehicle identification number. He had sold the car to someone in Georgia, a quarter century earlier.

So he called the Georgia department of motor vehicles. Turns out the car was still registered and on the road. But that’s all the office would say.

Siegrist got an attorney involved. Two weeks later, the lawyer called with a name and a phone number for a woman he believed to be the current owner. So Siegrist called.

“I was shocked,” says Tracy Swift, who teaches dental hygiene at Albany State University in Georgia. “He started the conversation with, ‘You’re going to find this phone call very weird.’” Swift thought she had a stalker, and recalls Siegrist saying, “I’m not crazy, I promise. Just let me tell you my story.”

Swift did drive a 1971 Beetle. She checked the VIN number and it was a match.

Siegrist traveled to Georgia, met Swift at her office, and drove the car in the parking lot. “I didn’t want to sell the car,” she says, “but because of his story, I felt like it needed to go back to its owner. It was the sweetest story.”

They agreed on a price (he says “many times over the original cost”) and the car showed up on a truck in Siegrist’s driveway days later. It was just before Christmas in 2022.

The first thing Siegrist and his wife did was drive around the block, with tears in their eyes. “Rudolph is back!” his wife yelled as they drove.

Siegrist went digging in a bucket full of coins and junk for a key chain. At the bottom, he found Rudolph’s original key. He didn’t remember saving it.

The Beetle needed restoration. So Siegrist asked advice from someone he trusted. Enter Keith, the rector at Siegrist’s church.

“When you’re at church,” Keith says, “and the service is over and everyone is filing out, that’s when folks share, often, important information about their lives.”

Keith, it turns out, had grown up the son of a car restorer and worked on cars himself in his garage. He was not a professional. He worried if he would have enough time. But a parishioner needed help. How could he say no?

It took about a year. “Aside from the paint and some engine work,” Keith says, “I ended up doing more than I was expecting, with no complaints whatsoever. In some ways, it was like I gained a parishioner. Only it was a car.”

In 2024, Siegrist began driving Rudolph around Pawleys Island. “Rarely can I go anywhere where somebody doesn’t stop me,” he says.

“Because probably 50% of the people of my generation have owned a Beetle or have had an adventure in a Beetle. People want to know the car’s story. So I tell it.”

As for Keith, he says, “It’s a point of pride that I had a hand in it.” Like most classic car stories, this one continues.

“As soon as Jeff stops finding little things for me to fix, then the story will be over,” he says. “But he keeps finding things for me to do! Which I don’t mind one bit.”

ABC Bullion has launched a pioneering investment product that allows Australians to draw regular cashflow from their precious metal holdings.

From office parties to NYE fireworks, here are the bottles that deserve pride of place in the ice bucket this season.