What’s Killing Productivity? Some Think It’s the Banks

Bank lending in the U.K. is going to property rather than innovative businesses

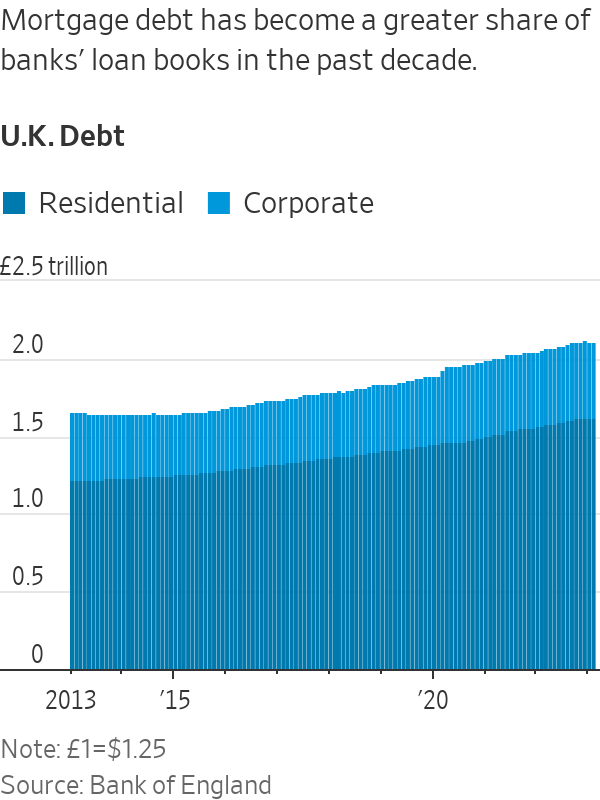

LONDON—The birthplace of the industrial revolution is in dire need of innovation. Standing in the way: Britain’s mortgage-laden banks.

The U.K.—inventor of the factory system, steam engine and passenger rail—is at the forefront of a 21st-century global productivity slowdown. Growth in U.K. productivity, or output per hour worked, has halved since the financial crisis, leading some policy makers to call this era Britain’s lost decade. Among the world’s seven largest developed economies, only Italy has fared worse.

The causes are hotly debated, and include an ageing population, tighter regulation and the U.K.’s departure from the European Union. But a factor that has gained special attention: the way U.K. banks have tilted lending to the booming housing market.

Bank lending for projects that boost economic output, such as machinery and software, has stagnated. Research and regulators say the two trends are linked: As real-estate prices soared, banks shifted more capital toward housing, viewed as less risky because the loans were backed by tangible assets with rising values.

“The banking system is increasingly becoming a brake on the economy,” said Jonathan Haskel, a member of the Bank of England’s Monetary Policy Committee.

The U.K. is an extreme example of what’s happened in big economies around the world for the better part of this century. Central banks cut interest rates in the 2010s through early 2022 to make it cheaper for businesses to borrow and invest. But while debt rose sharply, most of it went toward real estate.

The world’s total assets—including those held by households, businesses and banks—more than tripled from 2000 to 2020, according to a report from the McKinsey Global Institute, a research group. Two-thirds are stored in real estate; only a fifth are in productivity-boosting assets such as factories, equipment and infrastructure, McKinsey said. “The historic link between the growth of net worth and the growth of GDP no longer holds,” the report said.

Among the world’s 10 biggest economies, the U.K. is tied with France for having the lowest share of net worth in assets that boost economic growth. Meanwhile, the U.K.’s home values and mortgage debt have exploded.

U.K. banks added £400 billion, equivalent to about $500 billion, to home lending in the decade through this February, Bank of England data show. Debt extended to businesses grew by only one-tenth of that amount.

The U.K.’s big banks “pulled back in the financial crisis and never really came back” in terms of business lending, said Richard Davies, a former regional head for Barclays’s U.K. business banking operations who now leads Allica Bank, a London startup that lends to small and midsize businesses. “The big banks are obsessed with residential mortgages.”

The obsession with mortgages leaves some businesses feeling sidelined.

Geometric Manufacturing, based in Tewkesbury, England, makes defence and cybersecurity products. Several years ago the firm asked a U.K. bank for a loan to design and manufacture a robotic arm to load its machines, an investment that would allow the factory to produce more with fewer workers, Managing Director Paul Wenham said.

Despite the option for a government guarantee through a U.K. program to help small businesses, the bank declined to participate, Wenham said. The company eventually received a small loan from a London-based startup lender. The loan came with a high interest rate and was smaller than what the company had sought.

His inability to get a bigger loan delayed the project by years, Wenham said. “We could have been reaping the rewards and benefits so much sooner,” Wenham said.

Dozens of startup lenders have stepped in to fill the void created by the retrenchment of big banks. They provided about half of all new loans to small and midsize businesses last year, government figures show. But they charge high interest rates on business loans, said Mike Conroy, director of commercial finance at UK Finance, the banking industry’s main trade group.

Conroy said the biggest factor behind weak business investment is a lack of demand, not supply. Many entrepreneurs are reluctant to take on debt, or simply don’t aspire to grow, he said. “The U.K. has many small businesses making a great contribution to the U.K. economy and local communities, even though they don’t aspire to be the next Microsoft or Google,” Conroy said.

Research in the U.S. and Australia shows that banks respond to rising home values by shifting capital away from businesses. U.S. banks located in areas with robust housing markets in the early 2000s bubble boosted mortgage lending while cutting business lending, according to a 2018 research paper in the Review of Financial Studies.

In the U.K., rules put in place after the financial crisis force banks to hold higher levels of capital for business loans, which are deemed riskier, than for mortgages.

Matt Hammerstein, CEO of Barclays’s U.K. operations, said banks have increasingly required all borrowers—whether homeowners or businesses—to put up physical assets that the lenders could sell if the borrowers fail to repay. Many business owners refuse to put up their assets, such as homes, as collateral and thus don’t win approval for loans, he said.

“What banks have done over time in order to be able to underpin their risk appetite is to expect entrepreneurs to put more of their own equity at risk,” Hammerstein said. “If you’re lending to a small business, particularly one that has intangible assets, you’re going to want some collateral.”

Default rates among established small and midsize businesses is low—about one in 50 will default in a given year, said Davies of Allica Bank. But determining each company’s risk—and thus what interest rate to charge and how much capital to hold—is less accurate and more time-consuming for big banks, which have instead shifted resources to mortgages.

In 2018, Jurga Zilinskiene wanted financing to develop software to expand her London-based language-translation business, Guildhawk. The 40-employee company translates documents for companies around the globe.

She asked a big U.K. bank for a seven-figure loan; they lent her a fraction of that, citing her lack of tangible assets that could back the loan if she defaulted. Many of her assets are intangible, such as intellectual property.

She worries that banks are too focused on making a quick profit rather than supporting the long-term health of the economy. “How can I compete with global enterprises in the United States, China?” she asks.

Copyright 2020, Dow Jones & Company, Inc. All Rights Reserved Worldwide. LEARN MORE

Copyright 2020, Dow Jones & Company, Inc. All Rights Reserved Worldwide. LEARN MORE

This stylish family home combines a classic palette and finishes with a flexible floorplan

Just 55 minutes from Sydney, make this your creative getaway located in the majestic Hawkesbury region.

Impact investing is becoming more mainstream as larger, institutional asset owners drive more money into the sector, according to the nonprofit Global Impact Investing Network in New York.

In the GIIN’s State of the Market 2024 report, published late last month, researchers found that assets allocated to impact-investing strategies by repeat survey responders grew by a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of 14% over the last five years.

These 71 responders to both the 2019 and 2024 surveys saw their total impact assets under management grow to US$249 billion this year from US$129 billion five years ago.

Medium- and large-size investors were largely responsible for the strong impact returns: Medium-size investors posted a median CAGR of 11% a year over the five-year period, and large-size investors posted a median CAGR of 14% a year.

Interestingly, the CAGR of assets held by small investors dropped by a median of 14% a year.

“When we drill down behind the compound annual growth of the assets that are being allocated to impact investing, it’s largely those larger investors that are actually driving it,” says Dean Hand, the GIIN’s chief research officer.

Overall, the GIIN surveyed 305 investors with a combined US$490 billion under management from 39 countries. Nearly three-quarters of the responders were investment managers, while 10% were foundations, and 3% were family offices. Development finance institutions, institutional asset owners, and companies represented most of the rest.

The majority of impact strategies are executed through private-equity, but public debt and equity have been the fastest-growing asset classes over the past five years, the report said. Public debt is growing at a CAGR of 32%, and public equity is growing at a CAGR of 19%. That compares to a CAGR of 17% for private equity and 7% for private debt.

According to the GIIN, the rise in public impact assets is being driven by larger investors, likely institutions.

Private equity has traditionally served as an ideal way to execute impact strategies, as it allows investors to select vehicles specifically designed to create a positive social or environmental impact by, for example, providing loans to smallholder farmers in Africa or by supporting fledging renewable energy technologies.

Future Returns: Preqin expects managers to rely on family offices, private banks, and individual investors for growth in the next six years

But today, institutional investors are looking across their portfolios—encompassing both private and public assets—to achieve their impact goals.

“Institutional asset owners are saying, ‘In the interests of our ultimate beneficiaries, we probably need to start driving these strategies across our assets,’” Hand says. Instead of carving out a dedicated impact strategy, these investors are taking “a holistic portfolio approach.”

An institutional manager may want to address issues such as climate change, healthcare costs, and local economic growth so it can support a better quality of life for its beneficiaries.

To achieve these goals, the manager could invest across a range of private debt, private equity, and real estate.

But the public markets offer opportunities, too. Using public debt, a manager could, for example, invest in green bonds, regional bank bonds, or healthcare social bonds. In public equity, it could invest in green-power storage technologies, minority-focused real-estate trusts, and in pharmaceutical and medical-care company stocks with the aim of influencing them to lower the costs of care, according to an example the GIIN lays out in a separate report on institutional strategies.

Influencing companies to act in the best interests of society and the environment is increasingly being done through such shareholder advocacy, either directly through ownership in individual stocks or through fund vehicles.

“They’re trying to move their portfolio companies to actually solving some of the challenges that exist,” Hand says.

Although the rate of growth in public strategies for impact is brisk, among survey respondents investments in public debt totaled only 12% of assets and just 7% in public equity. Private equity, however, grabs 43% of these investors’ assets.

Within private equity, Hand also discerns more evidence of maturity in the impact sector. That’s because more impact-oriented asset owners invest in mature and growth-stage companies, which are favored by larger asset owners that have more substantial assets to put to work.

The GIIN State of the Market report also found that impact asset owners are largely happy with both the financial performance and impact results of their holdings.

About three-quarters of those surveyed were seeking risk-adjusted, market-rate returns, although foundations were an exception as 68% sought below-market returns, the report said. Overall, 86% reported their investments were performing in line or above their expectations—even when their targets were not met—and 90% said the same for their impact returns.

Private-equity posted the strongest results, returning 17% on average, although that was less than the 19% targeted return. By contrast, public equity returned 11%, above a 10% target.

The fact some asset classes over performed and others underperformed, shows that “normal economic forces are at play in the market,” Hand says.

Although investors are satisfied with their impact performance, they are still dealing with a fragmented approach for measuring it, the report said. “Despite this, over two-thirds of investors are incorporating impact criteria into their investment governance documents, signalling a significant shift toward formalising impact considerations in decision-making processes,” it said.

Also, more investors are getting third-party verification of their results, which strengthens their accountability in the market.

“The satisfaction with performance is nice to see,” Hand says. “But we do need to see more about what’s happening in terms of investors being able to actually track both the impact performance in real terms as well as the financial performance in real terms.”

This stylish family home combines a classic palette and finishes with a flexible floorplan

Just 55 minutes from Sydney, make this your creative getaway located in the majestic Hawkesbury region.