Why Businesses Can’t Stop Asking for Tips

Employers far beyond restaurants rely on the practice to avoid paying higher wages; testing customer limits

American businesses have gotten hooked on tipping.

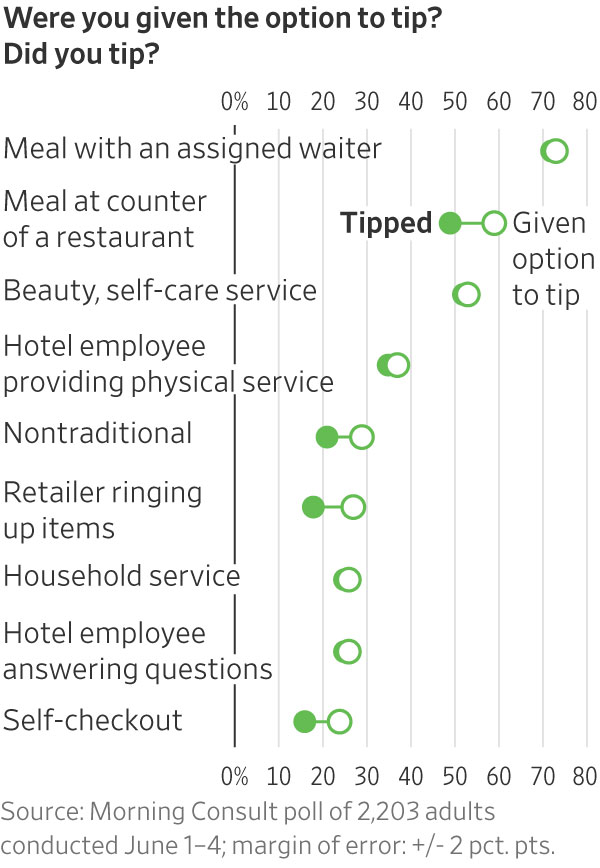

Tip requests have spread far beyond the restaurants and bars that have long relied on them to supplement employee wages. Juice shops, appliance-repair firms and even plant stores are among the service businesses now asking customers to hand over some extra money to their workers.

“The U.S. economy is more tip-reliant than it’s ever been,” said Scheherezade Rehman, an economist and professor of international finance at George Washington University. “But there’s a growing sense that these requests are getting out of control and that corporate America is dumping the responsibility for employee pay onto the customer.”

Some businesses that are new to tipping said they have turned to the practice to try to retain workers in a competitive job market while also keeping their prices low. Asking for tips allows them to increase worker pay without raising their wages.

Consumers seeing tip prompts at every turn say they are overwhelmed—and that worker wages should be business owners’ responsibility, not theirs.

Sixteen percent of the 517 small businesses surveyed by employee-management software company Homebase for The Wall Street Journal ask customers to leave a tip at checkout, up from 6.2% in 2019.

Payroll company Paychex, which provides software for thousands of businesses in leisure, hospitality, retail and other service industries, said more employees are receiving tips as a portion of their pay than at any time since the company started tracking tipping in 2010. As of May, 6.3% of workers whose employers used the software earned tips, compared with 5.6% in 2020. The number remained relatively flat between 2016 and 2020.

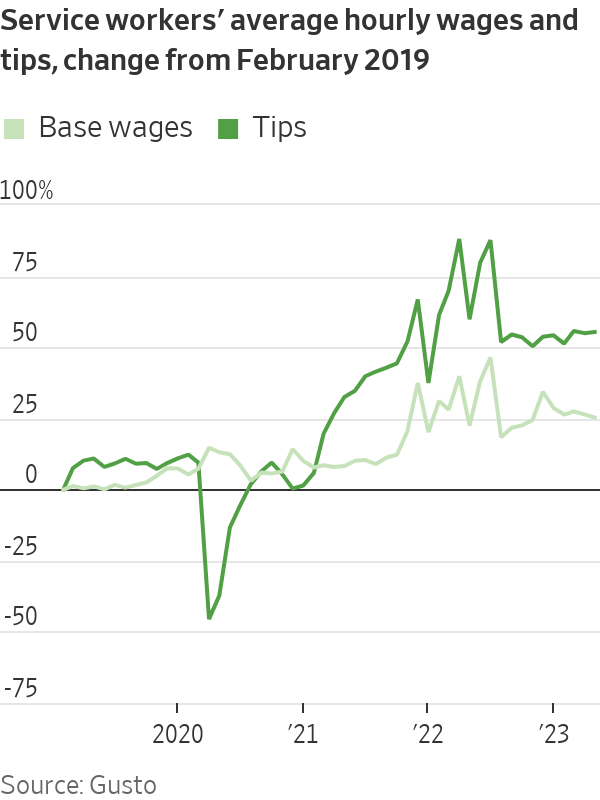

As of June, service-sector workers in non-restaurant leisure and hospitality jobs made $1.35 an hour in tips, on average, up 30% from the $1.04 an hour they made in 2019, according to an analysis of 300,000 small and midsize businesses by payroll provider Gusto.

Tips now increase wages for service workers by an average of 25%, compared with 20% between 2019 and 2020, according to Gusto. In May, the average hourly service-industry worker earned $16.64 an hour in base wages and $4.23 an hour in tips.

During pandemic lockdowns, customers of many service businesses began tipping to acknowledge workers who put themselves at risk. Rehman said that made businesses reliant on the practice. Employers with already tight margins say there’s no going back.

“With businesses still preparing for the possibility of a recession, they don’t want to lock into higher wages,” said Jonathan Morduch, a professor of public policy and economics at New York University. “Tipping gives them more flexibility.” He said the practice pushes the financial risk that employers would ordinarily shoulder onto workers.

“Businesses are happy to let workers earn more from tips, especially when there’s no pressure to raise the tipped minimum,” he said, referring to the $2.13 an hour plus tips many bar and restaurant workers across the country earn.

Holding on to workers has been especially difficult in the services sector, particularly since the pandemic. Lodging and food service have had the highest quit rate for workers since July 2021, consistently above 4.9% per three months, the U.S. Chamber of Commerce said in a May 2023 report. The quit rate for the retail trade industry isn’t far behind, around 3.3% so far in 2023. In May 2023, the overall quit rate for workers was 2.6%, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics.

Dan Moreno, founder of Miami-based Flamingo Appliance Service, decided in 2020 to add an option for customers to tip his employees, reasoning that his home-repair technicians were taking health risks by entering customers’ homes during the pandemic.

About one-third of customers now leave a tip of between 10% and 20%, Moreno said. The requests add an average of $650 a year to his 182 technicians’ salaries, about 1% of their total yearly income.

Rising costs, he said, persuaded him to retain the option after the pandemic abated.

“You wouldn’t believe the margins we operate with,” he said. Competition for workers is fierce. Were he to eliminate the gratuity prompt, he said, he would have to raise prices beyond the 18% he already has, on average, since 2019—likely costing him clients.

He knows the requests might turn off some customers, but as the son of a repair technician and a former technician himself, he said, he tries to do as much as he can for his workers.

Within the food-service industry, tips as a share of compensation are rising faster at limited-service establishments such as bakeries and coffee shops than at full-service ones, according to Gusto.

At the Main Squeeze Juice Co. in Mandeville, La., tips add $3 to $5 to workers’ hourly pay, which starts at $10. Owner Zachary Cheaney said he added the option when he opened the location in 2020.

“We can’t just say, ‘Oh, we’re going to charge $2 extra’ instead of having tips, because we have a duty to our customers to have a very fair price point,” said Cheaney, who also consults for Main Squeeze’s corporate office. If customers think the price is too high, he said, they won’t return. Asking them to tip, he said, is different because it’s optional.

“If customers completely stopped tipping, we would be forced to pay employees more, and it would be hard on us as business operators in this crazy environment of rising costs,” he said.

The juice bar’s general manager, Tiffany Naquin, said tips make up about one-tenth of her $46,000 annual pay. Workers like tips, she said, “in all industries. It’s that little extra.” Knowing a customer will see a gratuity screen at the end motivates employees, she said. “If you give employees incentives, they are going to give you better work,” she said.

Checkouts that include a tip screen are more awkward for customers than for workers, she said. She understands if someone declines to tip, she said, and she wouldn’t let that affect the quality of service.

Morduch, the New York University economics professor, said that while most people tend to think of tips as steady income, many businesses fluctuate seasonally—which means employee pay goes up and down. Service workers who receive tips, he added, are often lower income and struggle to deal with such volatility.

Saru Jayaraman, a labor advocate and director of the Food Labor Research Center at the University of California, Berkeley, said that boosting tips without increasing base pay is bad for workers. If customers stop tipping, she said, worker pay effectively declines, which it wouldn’t if employees got a raise.

“Employers think they’re being smart by using tipping instead of raising wages,” she said. “But really they’re risking losing staff, because it’s pissing consumers off and the employees are the ones who have to deal with it.”

A May survey of about 2,400 Americans by financial services company Bankrate found that consumers are tipping less often than they did at the height of the pandemic. Forty-one percent of respondents said businesses should pay their employees better rather than rely so much on tips. Roughly a third said tipping culture is out of hand.

Denver retiree Mary Medley, though, said she sees being a generous tipper as part of her economic responsibility. For her, it isn’t about how difficult a task was, but whether she can lighten someone else’s financial burden, even a little.

“It’s not my job to figure out where it goes or how it gets distributed,” she said. “But if they’re giving me the opportunity to participate in supporting a business in a tangible way, I’ll do so.”

Copyright 2020, Dow Jones & Company, Inc. All Rights Reserved Worldwide. LEARN MORE

Copyright 2020, Dow Jones & Company, Inc. All Rights Reserved Worldwide. LEARN MORE

This stylish family home combines a classic palette and finishes with a flexible floorplan

Just 55 minutes from Sydney, make this your creative getaway located in the majestic Hawkesbury region.

Continued stagflation and cost of living pressures are causing couples to think twice about starting a family, new data has revealed, with long term impacts expected

Australia is in the midst of a ‘baby recession’ with preliminary estimates showing the number of births in 2023 fell by more than four percent to the lowest level since 2006, according to KPMG. The consultancy firm says this reflects the impact of cost-of-living pressures on the feasibility of younger Australians starting a family.

KPMG estimates that 289,100 babies were born in 2023. This compares to 300,684 babies in 2022 and 309,996 in 2021, according to the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS). KPMG urban economist Terry Rawnsley said weak economic growth often leads to a reduced number of births. In 2023, ABS data shows gross domestic product (GDP) fell to 1.5 percent. Despite the population growing by 2.5 percent in 2023, GDP on a per capita basis went into negative territory, down one percent over the 12 months.

“Birth rates provide insight into long-term population growth as well as the current confidence of Australian families,” said Mr Rawnsley. “We haven’t seen such a sharp drop in births in Australia since the period of economic stagflation in the 1970s, which coincided with the initial widespread adoption of the contraceptive pill.”

Mr Rawnsley said many Australian couples delayed starting a family while the pandemic played out in 2020. The number of births fell from 305,832 in 2019 to 294,369 in 2020. Then in 2021, strong employment and vast amounts of stimulus money, along with high household savings due to lockdowns, gave couples better financial means to have a baby. This led to a rebound in births.

However, the re-opening of the global economy in 2022 led to soaring inflation. By the start of 2023, the Australian consumer price index (CPI) had risen to its highest level since 1990 at 7.8 percent per annum. By that stage, the Reserve Bank had already commenced an aggressive rate-hiking strategy to fight inflation and had raised the cash rate every month between May and December 2022.

Five more rate hikes during 2023 put further pressure on couples with mortgages and put the brakes on family formation. “This combination of the pandemic and rapid economic changes explains the spike and subsequent sharp decline in birth rates we have observed over the past four years,” Mr Rawnsley said.

The impact of high costs of living on couples’ decision to have a baby is highlighted in births data for the capital cities. KPMG estimates there were 60,860 births in Sydney in 2023, down 8.6 percent from 2019. There were 56,270 births in Melbourne, down 7.3 percent. In Perth, there were 25,020 births, down 6 percent, while in Brisbane there were 30,250 births, down 4.3 percent. Canberra was the only capital city where there was no fall in the number of births in 2023 compared to 2019.

“CPI growth in Canberra has been slightly subdued compared to that in other major cities, and the economic outlook has remained strong,” Mr Rawnsley said. “This means families have not been hurting as much as those in other capital cities, and in turn, we’ve seen a stabilisation of births in the ACT.”

This stylish family home combines a classic palette and finishes with a flexible floorplan

Just 55 minutes from Sydney, make this your creative getaway located in the majestic Hawkesbury region.