Why Employees Hate Hot-Desking

The shared workspace trend is growing, but researchers say many companies are doing it wrong

Hot-desking has some issues to work out.

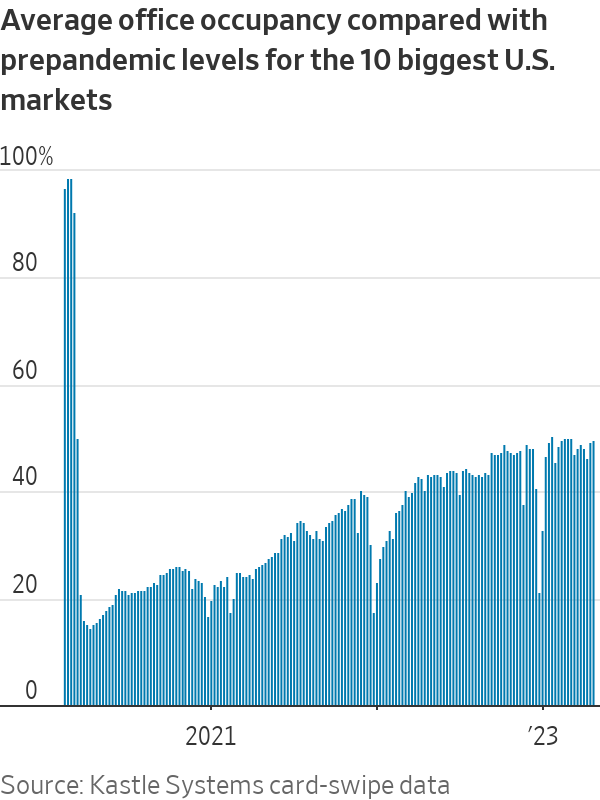

With nearly half of the pre pandemic office population in some major U.S. cities working remotely on any given day, hot-desking—where employees don’t have assigned desks but grab an empty one on days they come into the office—seems like a cost-saving no-brainer. The Gensler Research Institute’s 2022 U.S. Workplace Survey found that 19% of the office workers who responded had unassigned workspaces, compared with 10% in 2020.

There’s just one problem: Many employees hate it. They complain about the nuisance of having to hunt for a workspace every day they’re in the office, not being able to find a station that suits their needs, and no longer having a permanent space that they can personalise. Collaboration is harder, they say, and they feel less connected to their colleagues.

“The recurring labor, anxiety and rootlessness associated with hot-desking were emotionally and physically exhausting,” Manju Adikesavan, a Ph.D. candidate in environmental psychology at the City University of New York Graduate Center, wrote in a recently published paper. “Carrying work materials from place to place in campus buildings that were my workplaces made me feel like a visitor rather than a member of an academic community.”

The good news for companies is that it doesn’t have to be this way. For one thing, some people appreciate the opportunity to use a variety of workspaces and to engage with a broader range of colleagues. And research reveals that there are ways to minimise, and even eliminate, the negatives of hot-desking.

“It’s important for leaders and workers to understand that this style of working is a mind-set, that if done right, it can offer a lot of freedom,” says Christhina Candido, an associate professor of environmental and sustainable design at the University of Melbourne and a researcher of high-performance workplaces.

Feeling adrift

Unfortunately, in the rush to cope with the rise of remote work, many companies have implemented hot-desking without a lot of thought.

On one level, the problems with hot-desking are logistical. A review of 23 papers that looked at hot-desking in the past two decades was published in March in the Journal of Environmental Psychology. It observed that employees often found it impossible to locate the right kind of workstation for their needs—a cubicle with two monitors, perhaps, or a quiet standing desk, or a huddle room with a whiteboard, says Jennifer Veitch, a principal research officer at the National Research Council of Canada’s Construction Research Centre and co-author of the study.

Issues like these are more than just a personal annoyance, the study showed. Hot-deskers also often had difficulty finding colleagues with whom they wanted to collaborate, Dr. Veitch says. And managers often found it more difficult to manage their team because they weren’t always close to one another.

“The evidence does not show that more collaboration takes place when you throw people together in a soup of random desks,” Dr. Veitch says. “Yes, a lot of conversation might happen, but not all of that is helpful to the organisation.”

The lack of control was also an issue for some employees in the study—the inability to control social interactions and to always find the quiet spaces that workers needed to concentrate, Dr. Veitch says.

Then there is the difficulty of adjusting your workspace to suit your preferences when you’re not rooted in a given spot. “The challenge is that we are territorial people,” says Dr. Candido. “We like to have our photos up, our coffee mug out.”

Some workers have sought to reclaim that sense of personal space—undermining the whole concept of hot-desking in the process. David Courpasson, a professor of sociology and ethnography at Emlyon Business School in Lyon, France, recently researched a Belgian organisation whose workers practiced what he calls “objectal resistance” by unofficially strategizing collective ways to preserve a sense of ownership of their hot desks.

“We observed that many had decided to reappropriate desks by leaving personal items out—photos, stickers, bags, even crumbs from previous lunches,” Dr. Courpasson says of the research he conducted with Laurent Taskin, a professor of human resources and organisation studies at the Louvain School of Management in Belgium. The resistance wasn’t organized, he says, but it was discussed among employees. “Dissatisfaction was shared here and there, in corridor chats or during lunches and breaks,” he says.

There was similar resistance higher in the ranks as well. “Even leaders weren’t following the strict guidelines of the flex office process,” Dr. Courpasson says. Eventually, some team leaders gave in and allowed a bit of personalisation of shared workspaces, an approach the entire organisation now tolerates, says the professor.

A longer workday

Some hot-deskers complain about the time wasted seeking a workspace that suits their needs, and say the ways they address that problem have altered their work schedules and eaten into their personal time.

In her 2022 study, Ms. Adikesavan, the Ph.D. candidate, looked at doctoral students hot-desking on a U.S. university campus. She found that they often arrived early or worked late, when their office was less crowded, to avoid competing with colleagues for suitable workspaces. They also often wound up working well outside of the usual 9-to-5 hours in subscription-based co-working spaces, for which they weren’t reimbursed, as they tried to meet research or presentation deadlines, Ms. Adikesavan says.

Eva Bergsten, who has a doctorate in environmental and occupational medicine and is a research specialist at the University of Gavlë in Sweden, found similar problems in a study she recently published of companies that switched to hot-desking. Some employees she surveyed said that setup time stole precious work hours. “Not being able to change workplaces within the office smoothly—due to the wrong computer equipment or when the technology did not work optimally—was also a concern and very annoying,” and it made employees’ in-office time less productive, she says.

As with other logistical issues, these problems aren’t just personal irritations. A 2019 study by Annu Haapakangas, a chief researcher at the Finnish Institute of Occupational Health, found that the difficulty of locating colleagues in a hot-desking office damaged communication and the formation of communities.

The move to hot-desking, Dr. Haapakangas says, “may also increase perceived work demands, at least in the short term,” because less contact with colleagues and a weaker sense of community could create stress that leads people to feel that their work is more demanding than they previously thought.

All these problems for workers can become serious issues for their employers. Dr. Candido says dissatisfied workers who don’t feel supported in the office are more likely to leave an organization, and the costs of replacing talent can outweigh the cost-saving measures that hot-desking can provide.

Dr. Veitch says that kind of cost calculation isn’t always clear to a company’s leaders. “There is definitely a challenge between the human-resources people and the facilities-management people,” she says. “They may both report to the CFO, but the CFO might not be seeing the relationship between the cost to the building and the cost to the people in it. You can wind up with a real recruitment and retention problem.”

Making it work

However, research also suggests that hot-desking doesn’t have to be a disaster for employees. Some companies have adapted the basic model of hot-desking in ways that employees find attractive.

“I have seen success stories,” says Dr. Veitch. “The introduction of ‘neighbourhoods’ where people still have to move around but they become ‘natives’ to a home base area, as opposed to a desk, can work.”

So-called hoteling is another common solution that takes some of the day-to-day stress out of having to find a workspace: Employees book a specific space ahead of time, making it more likely that they can find the properly equipped workstation they need and eliminating the wasted time of searching for a spot upon arrival at the office.

Research also has found benefits from providing a mix of spaces with different ambiences, including some with privacy. Leroy Gonsalves, an assistant professor of management and organisations at the Questrom School of Business at Boston University, studied a big company that went from assigned cubicles to a mix of workspaces—quiet areas with high partitions, noisier open cafes, spaces for small meetings and conference rooms, in addition to hot desks. Workers’ control over their interactions with each other substantially increased, which they liked, the study found.

“People in our survey said that, if they sit with their team, colleagues come up to them constantly,” Dr. Gonsalves says. “But in an environment with hot desks and other variations—a library, a cafe-like setting, little cubicles—you can be social or you can intentionally hide away.”

“It gave employees agency to avoid unwanted interruptions while balancing individual tasks with professional obligations,” he says. “Employees felt that their productivity was judged less by time spent being seen, and more on their work outputs in the new office space. It seemed to work well.”

Carlos Martinez, a principal in Gensler’s New York office and creative director of the architectural firm’s Northeast region, says that nearly every corporate project he is working on incorporates hoteling and a mix of workspaces similar to the variety at the company Dr. Gonsalves studied. Cubicles for private phone calls, spaces for quiet concentration, large socialising areas and even outdoor space are common, he says. It’s important for these design elements to be specific to the needs of employees at each company, not based on a preset pattern, he says. “For a long time, the workplace was homogeneous,” Mr. Martinez says. “Now it’s very specific. One size does not fit all.”

Other research suggests the importance of setting up office rules around touchy issues such as cleanliness and quiet areas. Ms. Adikesavan’s research notes the value of providing lockers for employees to store items essential to their work where clean-desk policies are in place.

Management’s role

To get employees to buy into such a setup and come into the office with enthusiasm, companies need to first listen to workers and get their input on creating offices that fit their needs, says Dr. Bergsten of the University of Gavlë. Her 2021 study found that the more workers participated in activities that explained the change process, the higher their overall satisfaction.

Managers’ attitudes also are important, Dr. Bergsten says. In another recent study, she found that workers who perceived their leadership to be change-oriented and supportive of their employees during the transition to hot-desking were more productive after the change than those who didn’t feel that was the case. “Managers should be positive promoters” of this new way of working, she says.

Dr. Candido’s research similarly suggests the importance of company leadership in making hot-desking work. “You can’t be talking about sharing a space and then the manager is always working from the conference room,” the researcher says. “Top to bottom must embrace and engage or it just feels like a cost-saving exercise, which workers will notice.”

What she sees in the research on the topic, she says, is that if unassigned space is well designed and well managed, people will naturally organise at a group level and create a successful workplace. “If you want quiet, go there. If you want to have a coffee with colleagues, go there, etc.,” she says. “It becomes part of the office culture.”

Copyright 2020, Dow Jones & Company, Inc. All Rights Reserved Worldwide. LEARN MORE

Copyright 2020, Dow Jones & Company, Inc. All Rights Reserved Worldwide. LEARN MORE

This stylish family home combines a classic palette and finishes with a flexible floorplan

Just 55 minutes from Sydney, make this your creative getaway located in the majestic Hawkesbury region.

Continued stagflation and cost of living pressures are causing couples to think twice about starting a family, new data has revealed, with long term impacts expected

Australia is in the midst of a ‘baby recession’ with preliminary estimates showing the number of births in 2023 fell by more than four percent to the lowest level since 2006, according to KPMG. The consultancy firm says this reflects the impact of cost-of-living pressures on the feasibility of younger Australians starting a family.

KPMG estimates that 289,100 babies were born in 2023. This compares to 300,684 babies in 2022 and 309,996 in 2021, according to the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS). KPMG urban economist Terry Rawnsley said weak economic growth often leads to a reduced number of births. In 2023, ABS data shows gross domestic product (GDP) fell to 1.5 percent. Despite the population growing by 2.5 percent in 2023, GDP on a per capita basis went into negative territory, down one percent over the 12 months.

“Birth rates provide insight into long-term population growth as well as the current confidence of Australian families,” said Mr Rawnsley. “We haven’t seen such a sharp drop in births in Australia since the period of economic stagflation in the 1970s, which coincided with the initial widespread adoption of the contraceptive pill.”

Mr Rawnsley said many Australian couples delayed starting a family while the pandemic played out in 2020. The number of births fell from 305,832 in 2019 to 294,369 in 2020. Then in 2021, strong employment and vast amounts of stimulus money, along with high household savings due to lockdowns, gave couples better financial means to have a baby. This led to a rebound in births.

However, the re-opening of the global economy in 2022 led to soaring inflation. By the start of 2023, the Australian consumer price index (CPI) had risen to its highest level since 1990 at 7.8 percent per annum. By that stage, the Reserve Bank had already commenced an aggressive rate-hiking strategy to fight inflation and had raised the cash rate every month between May and December 2022.

Five more rate hikes during 2023 put further pressure on couples with mortgages and put the brakes on family formation. “This combination of the pandemic and rapid economic changes explains the spike and subsequent sharp decline in birth rates we have observed over the past four years,” Mr Rawnsley said.

The impact of high costs of living on couples’ decision to have a baby is highlighted in births data for the capital cities. KPMG estimates there were 60,860 births in Sydney in 2023, down 8.6 percent from 2019. There were 56,270 births in Melbourne, down 7.3 percent. In Perth, there were 25,020 births, down 6 percent, while in Brisbane there were 30,250 births, down 4.3 percent. Canberra was the only capital city where there was no fall in the number of births in 2023 compared to 2019.

“CPI growth in Canberra has been slightly subdued compared to that in other major cities, and the economic outlook has remained strong,” Mr Rawnsley said. “This means families have not been hurting as much as those in other capital cities, and in turn, we’ve seen a stabilisation of births in the ACT.”

This stylish family home combines a classic palette and finishes with a flexible floorplan

Just 55 minutes from Sydney, make this your creative getaway located in the majestic Hawkesbury region.