China’s Fading Recovery Reveals Deeper Economic Struggles

Ballooning debt, tepid consumption and worsening relations with the West to weigh on growth, economists say

China’s era of rapid growth is over. Its recovery from zero-Covid is stalling. And now the country is facing deep, structural problems in its economy.

The outlook was better just a few months ago, after Beijing lifted its draconian Covid-19 controls, setting off a flurry of spending as people ate out and splurged on travel.

But as the sugar high of the reopening wears off, underlying problems in China’s economy that have been building for years are reasserting themselves.

The property boom and government over investment that fuelled growth for more than a decade have ended. Enormous debts are crippling households and local governments. Some families, worried about the future, are hoarding cash.

Chinese leader Xi Jinping’s crackdowns on private enterprise have discouraged risk-taking, while deteriorating relations with the West—exemplified by a new campaign against international due-diligence and consulting firms—are stifling foreign investment.

Economists say these worsening structural problems are hobbling China’s chances of extending the growth miracle that transformed it into a rival to the U.S. for global power and influence.

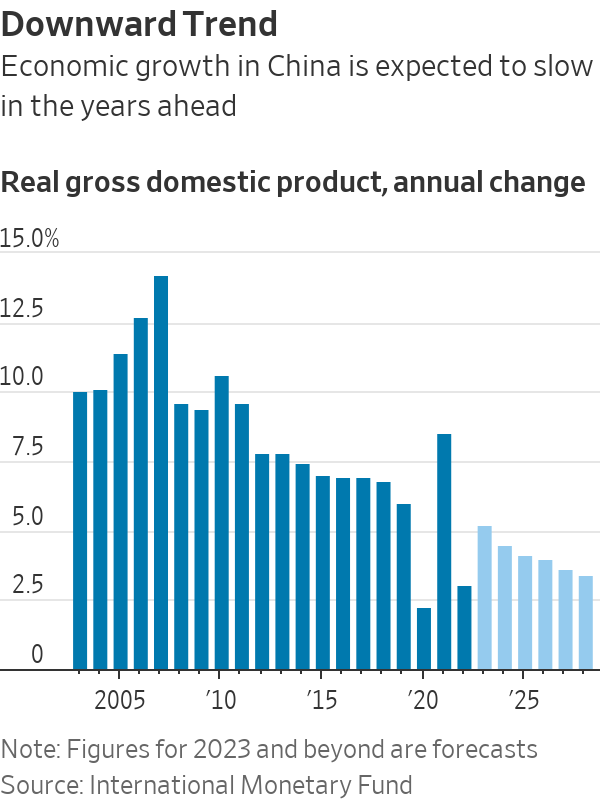

Instead of expanding at 6% to 8% a year as was common in the past, China might soon be heading toward growth of 2% or 3%, some economists say. An ageing population and shrinking workforce compound its difficulties.

China could drive less global growth this year and beyond than many business leaders expected, making the country less important for some foreign companies, and less likely to significantly surpass the U.S. as the world’s biggest economy.

“The disappointing recovery today really suggests that some of the structural drags are already in play,” said Frederic Neumann, chief Asia economist at HSBC.

China’s economy expanded at an annual rate of 4.5% in the first quarter, boosted by the end of Covid-era restrictions.

Yet more recent signals suggest the revival is ebbing. Retail sales rose 0.5% in April compared with March. A bundle of data on factory output, exports and investment came in much weaker than economists were expecting.

More than a fifth of Chinese youths aged 16 to 24 were unemployed in April. E-commerce companies Alibaba and JD.com reported lacklustre first-quarter earnings. Hong Kong’s Hang Seng Index, dominated by Chinese companies, is down 5.2% year to date, and the yuan has weakened against the U.S. dollar.

Most economists don’t expect China’s problems to lead to recession, or derail the government’s growth target of around 5% this year, which is widely seen as easily achievable given how weak the economy was last year.

McDonald’s and Starbucks have said they are opening hundreds of new restaurants in China, while retailers including Ralph Lauren are launching new stores.

A boom in electric-vehicle production allowed China to surpass Japan as the world’s largest exporter of vehicles in the first quarter. Beijing’s industrial policies and China’s manufacturing prowess mean it is still finding ways to succeed in some major industries.

“We still have confidence in the long-term growth story of China,” said Phillip Wool, head of research at Rayliant Global Advisors, an asset manager with $17 billion under management. He said the country’s transition to one that relies more on domestic consumption instead of exports will help keep it on track.

Still, many economists are growing more worried about China’s future.

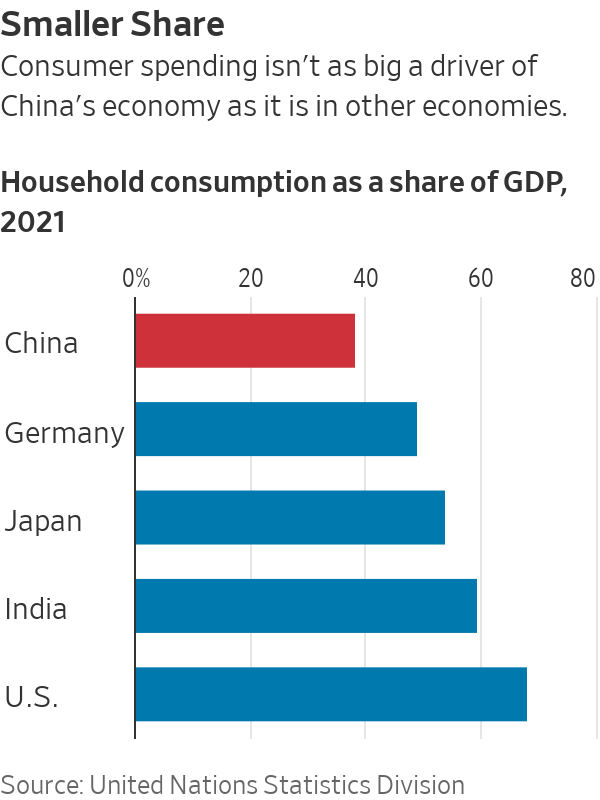

The big hope for this year was that Chinese consumers would step up spending, as the main drivers of China’s past growth—investment and exports—languish.

But while people are spending somewhat more after almost three years of tough Covid-19 controls, China isn’t experiencing the kind of surge other economies enjoyed when they emerged from the pandemic.

Consumer confidence is low. More important, some economists say, is that Beijing hasn’t been able to meaningfully change Chinese consumers’ long-running propensity to save rather than spend—a response to a threadbare social-safety net that means families must sock away more for medical bills and other emergencies.

Chinese household consumption accounts for around 38% of annual gross domestic product, according to United Nations data, compared with 68% in the U.S.

“Consumer-led growth has always been a bit of an aspirational target” for China, said Louise Loo, China lead economist in Singapore at Oxford Economics, a consulting firm. Now, it might be even harder to achieve, she said, given how cautious Chinese consumers are coming out of the pandemic.

Although Beijing is trying to make it easier to borrow this year, lending data indicate households prefer to pay down debt than take on new loans.

In March, Zi Lu dipped into her dowry and paid off the remaining 1.2 million yuan, equivalent to about $170,000, on her mortgage for an apartment she bought in Shanghai two years ago. Working for an e-commerce retailer, she said sales have been underwhelming this year. Lu said she is anxious and wants to reduce her debt burden.

“I’m scared of getting laid off out of the blue,” she said.

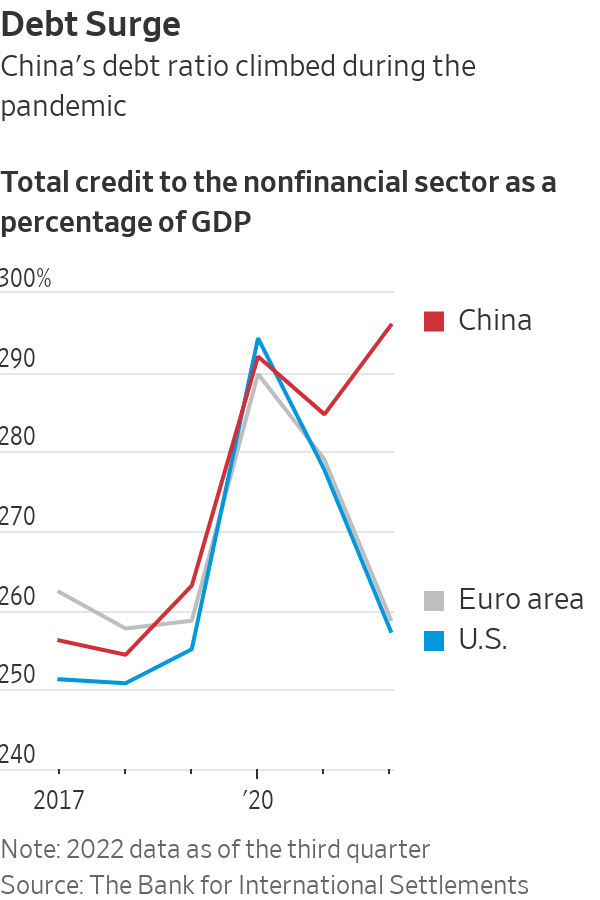

Also looming over the economy is its massive debt pile.

Between 2012 and 2022, China’s debt grew by $37 trillion, while the U.S. added nearly $25 trillion. By June 2022, debt in China reached about $52 trillion, dwarfing outstanding debt in all other emerging markets combined, according to calculations by Nicholas Borst, director of China research at Seafarer Capital Partners.

As of last September, total debt as a share of GDP hit 295% in China, compared with 257% in the U.S., data from the Bank for International Settlements shows.

Viewing the debt buildup as a threat to financial stability, Xi has made deleveraging a centrepiece of his economic policy since 2016, weighing on growth.

To help deflate the country’s housing bubble, regulators imposed strict borrowing limits for property developers from late 2020. Property development investment fell 5.8% in the first quarter of this year despite policy efforts to stem the pace of the slide.

Two-thirds of local governments are now in danger of breaching unofficial debt thresholds set by Beijing to signify severe funding stress, according to S&P Global calculations. Cities across the country from Shenzhen to Zhengzhou have cut benefits for civil servants and delayed salary payments in some cases for teachers.

These problems are deepening when China’s appeal as a destination for foreign firms is waning, data show, as tensions rise with the U.S.-led West.

Foreign direct investment into China tumbled 48% in 2022 compared with a year earlier, to $180 billion, according to Chinese data, while FDI as a share of China’s GDP has slipped to less than 2%, from more than double that a decade ago.

Competition for investment with countries including India and Vietnam is heating up as firms seek to diversify supply chains, partly in response to the risk of disruption from conflict between the U.S. and China.

Jens Eskelund, president of the European Union Chamber of Commerce in China, said uncertainty over China’s long-term economic prospects is another factor in companies’ investment decisions.

“Naturally, it dampens the willingness to go out and invest in additional capacity if you are not super optimistic about the economic outlook,” he said.

Reforms to foster more productive, private-sector activity have stalled under Xi, who is placing greater emphasis on security than economic growth. Beijing has tightened regulation of sectors including technology, private education and real estate, leaving many business owners unwilling to invest more.

In the first four months of this year, fixed-asset investment made by private firms grew 0.4% from a year earlier, compared with 5.5% growth in the same period in 2019.

Chinese leaders have dialled up rhetoric to reassure entrepreneurs and investors. Li Qiang, China’s No. 2 official and new premier, said in March that China will open further to foreign players, and told Communist Party officials to treat private entrepreneurs as “our own people.”

Economists are split over whether policy makers, who have held off on launching large-scale stimulus as they did in 2008 and 2015, will resort to more aggressive stimulus now. Some, including economists from Citigroup, expect China’s central bank to cut interest rates in the coming months to lift sentiment.

Others say that Beijing’s restraint stems from fear of compounding already-high debt levels, and that more stimulus might do little to trigger demand for credit anyway.

Jeff Bowman, chief executive of Cocona, which makes temperature-regulating materials used in apparel and bedding, said he is still optimistic about China. He said that during a recent two-week business trip to Taiwan and China, customers who were focused on China’s domestic market were far more upbeat than their counterparts exporting to the U.S. or Europe, who he said “are hurting for sure.”

He said that Cocona, based in Boulder, Colo., plans to set up a subsidiary in China to expand its business there.

But many analysts still wonder where the growth will come from.

“The big question is, have we reached the point where awareness of the structural slowdown is becoming a near-term issue for confidence? Then it’s a bit of a vicious cycle,” said Michael Hirson, head of China research at 22V Research, a New York-based consulting firm.

Copyright 2020, Dow Jones & Company, Inc. All Rights Reserved Worldwide. LEARN MORE

Copyright 2020, Dow Jones & Company, Inc. All Rights Reserved Worldwide. LEARN MORE

This stylish family home combines a classic palette and finishes with a flexible floorplan

Just 55 minutes from Sydney, make this your creative getaway located in the majestic Hawkesbury region.

Continued stagflation and cost of living pressures are causing couples to think twice about starting a family, new data has revealed, with long term impacts expected

Australia is in the midst of a ‘baby recession’ with preliminary estimates showing the number of births in 2023 fell by more than four percent to the lowest level since 2006, according to KPMG. The consultancy firm says this reflects the impact of cost-of-living pressures on the feasibility of younger Australians starting a family.

KPMG estimates that 289,100 babies were born in 2023. This compares to 300,684 babies in 2022 and 309,996 in 2021, according to the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS). KPMG urban economist Terry Rawnsley said weak economic growth often leads to a reduced number of births. In 2023, ABS data shows gross domestic product (GDP) fell to 1.5 percent. Despite the population growing by 2.5 percent in 2023, GDP on a per capita basis went into negative territory, down one percent over the 12 months.

“Birth rates provide insight into long-term population growth as well as the current confidence of Australian families,” said Mr Rawnsley. “We haven’t seen such a sharp drop in births in Australia since the period of economic stagflation in the 1970s, which coincided with the initial widespread adoption of the contraceptive pill.”

Mr Rawnsley said many Australian couples delayed starting a family while the pandemic played out in 2020. The number of births fell from 305,832 in 2019 to 294,369 in 2020. Then in 2021, strong employment and vast amounts of stimulus money, along with high household savings due to lockdowns, gave couples better financial means to have a baby. This led to a rebound in births.

However, the re-opening of the global economy in 2022 led to soaring inflation. By the start of 2023, the Australian consumer price index (CPI) had risen to its highest level since 1990 at 7.8 percent per annum. By that stage, the Reserve Bank had already commenced an aggressive rate-hiking strategy to fight inflation and had raised the cash rate every month between May and December 2022.

Five more rate hikes during 2023 put further pressure on couples with mortgages and put the brakes on family formation. “This combination of the pandemic and rapid economic changes explains the spike and subsequent sharp decline in birth rates we have observed over the past four years,” Mr Rawnsley said.

The impact of high costs of living on couples’ decision to have a baby is highlighted in births data for the capital cities. KPMG estimates there were 60,860 births in Sydney in 2023, down 8.6 percent from 2019. There were 56,270 births in Melbourne, down 7.3 percent. In Perth, there were 25,020 births, down 6 percent, while in Brisbane there were 30,250 births, down 4.3 percent. Canberra was the only capital city where there was no fall in the number of births in 2023 compared to 2019.

“CPI growth in Canberra has been slightly subdued compared to that in other major cities, and the economic outlook has remained strong,” Mr Rawnsley said. “This means families have not been hurting as much as those in other capital cities, and in turn, we’ve seen a stabilisation of births in the ACT.”

This stylish family home combines a classic palette and finishes with a flexible floorplan

Just 55 minutes from Sydney, make this your creative getaway located in the majestic Hawkesbury region.