Dating Apps Once Ran on Novelty. For Some Users, the Fun Is Over.

Ad campaigns for online dating companies have become flashpoints for frustrated online daters

As online-dating apps court new and younger audiences, some of their marketing efforts are turning off daters instead.

Bumble last month apologised for ads making light of women so frustrated with online dating that they would consider celibacy. The League, a dating app targeting “the overly ambitious,” was called “ick-inducing” for its recent ad campaign, which included taglines like “Date someone with a 5-year-plan that makes you want to ovulate.” And Hinge’s years-long “Designed to Be Deleted” campaign has started to fall flat for longtime users still looking for love on their phones.

Online dating continues to play a lead role in the romantic lives of millions of Americans. Around half of all U.S. adults under 30 have used a dating site or app at some point in their lives, and one in 10 adults with partners say they met their significant other by dating online, according to Pew Research Center data. And the industry’s biggest players, Match Group and Bumble, now generate annual revenues north of $3.4 billion and $1.1 billion, respectively.

But the ad campaigns have high stakes for online dating companies trying to achieve the right mix of user acquisition and pricing power to re-interest Wall Street in a saturated sector.

Online-dating growth has been slowing. Paying users declined 6% in the first quarter of the year at Match Group, whose portfolio includes the League, Tinder and Hinge, compared with a 3% dip in the first quarter of 2023. The Bumble app grew paying users 18% in the first quarter, compared with 31% growth in the period a year earlier.

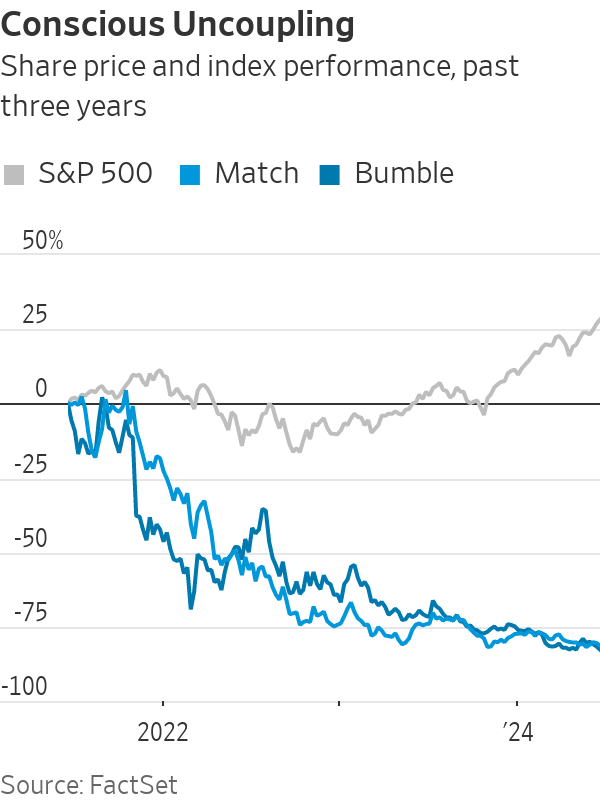

Shares in both have fallen this year even as the S&P 500 rose. And some singles have become perhaps as wary as investors.

Nearly half of all online daters and more than half of female daters say their experiences have been negative, according to Pew , and a growing tide of users are sharing their dissatisfaction in popular Facebook forums and on TikTok. People bemoan a perceived rise in bad dating etiquette such as “ghosting” and the sending of unsolicited sexual messages, and blame the way online romance makes it easier to discard potential partners at a touch of a button. “Hacks,” or tricks designed to game the apps for better dates, abound, demonstrating the shortcomings of their designs.

And the companies’ growing emphasis on pricier premium services is giving users new reasons to scrutinise the algorithmically driven path to romance.

Bumble made its name as a free app that only let women make the first move, for example. But since 2016, it has charged for advantages such as unlimited “swipes” to connect with prospects. The most expensive plan today costs $80 a month. Nonpaying users on Bumble and other apps can hit a limit, which some say leaves them taunted by the nagging fear that their perfect partners are hidden just on the other side of a paywall.

In this environment, new ad campaigns have become a release valve for the tension.

Failure to launch

Bumble users had hoped change was on the way after a teaser campaign depicted a discouraged dater joining a convent but happily leaving after being handed the Bumble app. “We’ve changed so you don’t have to,” one of the ads promised.

“At this point, it’s the app’s responsibility not to rebrand, but to pivot technologically,” said Michelle Khouri , the founder of creator platform Recordical , who has been using dating apps on and off for 10 years following her divorce from a man she met through online dating service eHarmony.

But Bumble’s big move wasn’t a fundamental overhaul: The company was letting women put questions on their profiles to which men they matched with could respond without a specific invitation.

Disappointment became backlash when the full ad campaign included billboards that declared, “Thou shalt not give up on dating and become a nun” and “You know full well a vow of celibacy is not the answer.”

Female daters often thinly disguise their dissatisfaction with modern dating by joking about giving it up for a life of spinsterhood, and Bumble had done what all marketers try to do—joined the conversation .

The problem for many was that Bumble’s quips about nunneries located the problem in daters’ resilience, as opposed to the dating apps themselves, and the unfavourable dating culture some users say the apps’ owners have been complicit in fuelling.

“Bumble was a brand that built its identity on empowering women and then they absolutely laughed in our faces,” said Michelle Wintersteen, the founder and chief executive of branding and marketing agency MKW Creative and a former Bumble user who grew frustrated by its paywalls.

Bumble took down the billboards and made several public apologies.

“We just made a mistake in how that landed. It was not good and we felt really terrible about it,” Bumble CEO Lidiane Jones said at a Wall Street Journal event last month.

Jones added in an emailed statement that the company is enhancing its internal and external review processes, and “actively engaging in conversations to ensure our marketing tone matches the 10 years Bumble has dedicated to championing women and creating safe, respectful, and empowering spaces for connection.”

Some online-dating executives and observers think the gripes with dating apps are largely an extension of age-old ennui over the search for lasting love.

“This is not a new phenomenon, and I think that dating apps have crystallised and brought those concerns to the fore, primarily because the prior institutions that were responsible for connecting individuals—such as family, friends, churches, other homes of worship—were not able to assume blame in the same way,” said Jess Carbino, a sociologist who has worked as a consultant for Bumble and Tinder.

Pickup lines

When the League introduced its “Be a GoalDigger” brand campaign in 2023, its first big marketing effort since being acquired by Match Group in 2022, some had visceral reactions.

“Whoever is behind this truly thought they were like, hitting Gen -Z, being super edgy and cool,” said the TikTok user who reported getting the “ick” from its campaign. “In reality, it is the most millennial, cringy thing that makes you want to actually convulse.”

The app has “never been afraid of speaking up or speaking out about the kind of people that The League attracts,” said Lisa Kraynak, senior vice president of marketing for the League, in a statement. In addition to its ad mentioning ovulation, others read: “Find Your Goal Mate” and “Date Someone With Big Goal Energy.”

“We know that we aren’t for everyone, and that is a core part of our value proposition,” Kraynak added, noting that a number of people responded well to it.

Unlike apps such as Tinder and Bumble, the League requires profile approval to join. On the app, users get three to five prospects a day unless they upgrade to become a paying member, which runs $99 a week or $399 for a three-month subscription. Once a match is made in the app, users have 14 days to initiate a conversation before the matches expire.

Fighting flakes

These components, as well as features such as a “flakiness score” indicating which users have a habit of matching but not chatting, are why Kraynak said the League is “designed to combat the dissatisfaction with apps today .”

Tinder has leaned away from the celebration of singledom that it embraced in a 2018 brand campaign that called single “a terrible thing to waste.” While the app has long been associated with hookups, the company has more recently emphasised the various relationships that can result from its app. Its marketing now romanticizes “a toothbrush at their place” and “comfortable silences,” all while it seeks to upsell users.

“It was about shedding a perception that was too narrow and not accurate,” said Melissa Hobley, chief marketing officer at Tinder.

Hinge, the Match Group brand that has long positioned itself as an app for finding relationships rather than hookups, continues to iterate on its “Designed to Be Deleted” campaign launched in 2019. The company has refreshed the campaign every year since then with the same tagline.

On social media, some dissatisfied users say they have deleted the app—not because they found love but because the app didn’t work for them. Hinge said every feature is designed to help daters be intentional and that it is looking for ways to address dating burnout.

Chief Marketing Officer Jackie Jantos said Hinge is the fastest-growing major dating app.

“‘Designed to Be Deleted,’ as an idea and a marketing program, continues to help us build our base of users,” Jantos said.

Match Group said Hinge’s direct revenue grew 50% in the first quarter of the year as paying members increased 31% and revenue per payer rose 14%. It offers two types of subscriptions, Hinge+ and HingeX, which start at $14.99 and $24.99, respectively, a week.

More recently, the company partnered with a social-media brand that interviews couples on the street, to circulate their love stories that involve Hinge.

“We know that our best growth comes from organic success stories of people meeting on Hinge,” added Jantos.

Copyright 2020, Dow Jones & Company, Inc. All Rights Reserved Worldwide. LEARN MORE

Copyright 2020, Dow Jones & Company, Inc. All Rights Reserved Worldwide. LEARN MORE

A divide has opened in the tech job market between those with artificial-intelligence skills and everyone else.

A 30-metre masterpiece unveiled in Monaco brings Lamborghini’s supercar drama to the high seas, powered by 7,600 horsepower and unmistakable Italian design.

A divide has opened in the tech job market between those with artificial-intelligence skills and everyone else.

There has rarely, if ever, been so much tech talent available in the job market. Yet many tech companies say good help is hard to find.

What gives?

U.S. colleges more than doubled the number of computer-science degrees awarded from 2013 to 2022, according to federal data. Then came round after round of layoffs at Google, Meta, Amazon, and others.

The Bureau of Labor Statistics predicts businesses will employ 6% fewer computer programmers in 2034 than they did last year.

All of this should, in theory, mean there is an ample supply of eager, capable engineers ready for hire.

But in their feverish pursuit of artificial-intelligence supremacy, employers say there aren’t enough people with the most in-demand skills. The few perceived as AI savants can command multimillion-dollar pay packages. On a second tier of AI savvy, workers can rake in close to $1 million a year .

Landing a job is tough for most everyone else.

Frustrated job seekers contend businesses could expand the AI talent pipeline with a little imagination. The argument is companies should accept that relatively few people have AI-specific experience because the technology is so new. They ought to focus on identifying candidates with transferable skills and let those people learn on the job.

Often, though, companies seem to hold out for dream candidates with deep backgrounds in machine learning. Many AI-related roles go unfilled for weeks or months—or get taken off job boards only to be reposted soon after.

Playing a different game

It is difficult to define what makes an AI all-star, but I’m sorry to report that it’s probably not whatever you’re doing.

Maybe you’re learning how to work more efficiently with the aid of ChatGPT and its robotic brethren. Perhaps you’re taking one of those innumerable AI certificate courses.

You might as well be playing pickup basketball at your local YMCA in hopes of being signed by the Los Angeles Lakers. The AI minds that companies truly covet are almost as rare as professional athletes.

“We’re talking about hundreds of people in the world, at the most,” says Cristóbal Valenzuela, chief executive of Runway, which makes AI image and video tools.

He describes it like this: Picture an AI model as a machine with 1,000 dials. The goal is to train the machine to detect patterns and predict outcomes. To do this, you have to feed it reams of data and know which dials to adjust—and by how much.

The universe of people with the right touch is confined to those with uncanny intuition, genius-level smarts or the foresight (possibly luck) to go into AI many years ago, before it was all the rage.

As a venture-backed startup with about 120 employees, Runway doesn’t necessarily vie with Silicon Valley giants for the AI job market’s version of LeBron James. But when I spoke with Valenzuela recently, his company was advertising base salaries of up to $440,000 for an engineering manager and $490,000 for a director of machine learning.

A job listing like one of these might attract 2,000 applicants in a week, Valenzuela says, and there is a decent chance he won’t pick any of them. A lot of people who claim to be AI literate merely produce “workslop”—generic, low-quality material. He spends a lot of time reading academic journals and browsing GitHub portfolios, and recruiting people whose work impresses him.

In addition to an uncommon skill set, companies trying to win in the hypercompetitive AI arena are scouting for commitment bordering on fanaticism .

Daniel Park is seeking three new members for his nine-person startup. He says he will wait a year or longer if that’s what it takes to fill roles with advertised base salaries of up to $500,000.

He’s looking for “prodigies” willing to work seven days a week. Much of the team lives together in a six-bedroom house in San Francisco.

If this sounds like a lonely existence, Park’s team members may be able to solve their own problem. His company, Pickle, aims to develop personalised AI companions akin to Tony Stark’s Jarvis in “Iron Man.”

Overlooked

James Strawn wasn’t an AI early adopter, and the father of two teenagers doesn’t want to sacrifice his personal life for a job. He is beginning to wonder whether there is still a place for people like him in the tech sector.

He was laid off over the summer after 25 years at Adobe , where he was a senior software quality-assurance engineer. Strawn, 55, started as a contractor and recalls his hiring as a leap of faith by the company.

He had been an artist and graphic designer. The managers who interviewed him figured he could use that background to help make Illustrator and other Adobe software more user-friendly.

Looking for work now, he doesn’t see the same willingness by companies to take a chance on someone whose résumé isn’t a perfect match to the job description. He’s had one interview since his layoff.

“I always thought my years of experience at a high-profile company would at least be enough to get me interviews where I could explain how I could contribute,” says Strawn, who is taking foundational AI courses. “It’s just not like that.”

The trouble for people starting out in AI—whether recent grads or job switchers like Strawn—is that companies see them as a dime a dozen.

“There’s this AI arms race, and the fact of the matter is entry-level people aren’t going to help you win it,” says Matt Massucci, CEO of the tech recruiting firm Hirewell. “There’s this concept of the 10x engineer—the one engineer who can do the work of 10. That’s what companies are really leaning into and paying for.”

He adds that companies can automate some low-level engineering tasks, which frees up more money to throw at high-end talent.

It’s a dynamic that creates a few handsomely paid haves and a lot more have-nots.

An opulent Ryde home, packed with cinema, pool, sauna and more, is hitting the auction block with a $1 reserve.

On October 2, acclaimed chef Dan Arnold will host an exclusive evening, unveiling a Michelin-inspired menu in a rare masterclass of food, storytelling and flavour.