Fed Raises Rates but Nods to Greater Uncertainty After Banking Stress

Officials voted unanimously to increase their benchmark short-term rate by a quarter percentage point

The Federal Reserve approved another quarter-percentage-point interest-rate increase but signalled that banking-system turmoil might end its rate-rise campaign sooner than seemed likely two weeks ago.

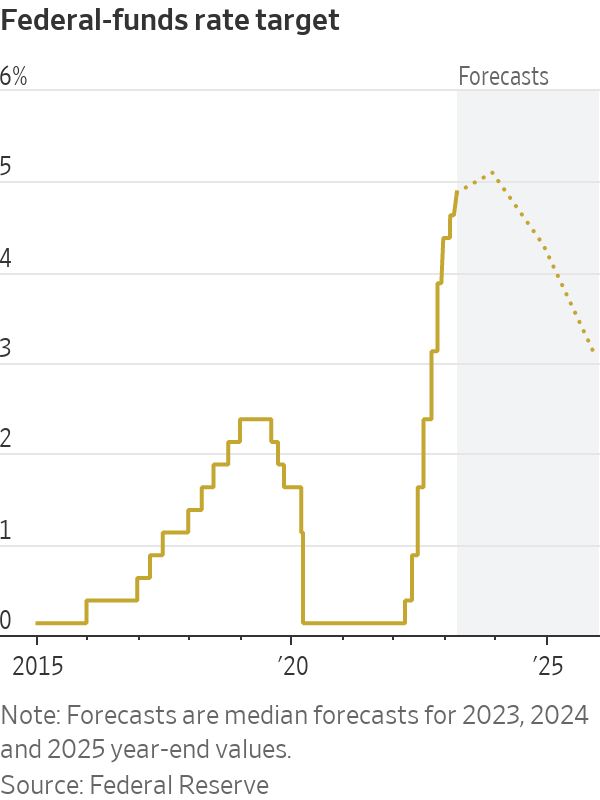

The decision Wednesday marked the Fed’s ninth consecutive rate increase aimed at battling inflation over the past year. It will bring its benchmark federal-funds rate to a range between 4.75% and 5%, the highest level since September 2007.

Officials sent a hint that they might be done raising interest rates soon in their post meeting policy statement. “The committee anticipates that some additional policy firming may be appropriate,” the statement said. Officials dropped a phrase used in their previous eight statements that said the committee anticipated “ongoing increases” in rates would be appropriate.

The policy statement said it was too soon to tell how much recent banking stress would slow the economy. “The U.S. banking system is sound and resilient,” the statement said. “Recent developments are likely to result in tighter credit conditions for households and businesses and to weigh on economic activity, hiring, and inflation. The extent of these effects is uncertain.”

All 11 voters on the rate-setting Federal Open Market Committee agreed to the decision.

New projections showed 17 out of 18 officials who participated in the meeting expect the fed-funds rate to rise to at least 5.1% and to stay there through December, implying one more quarter-point increase. The quarterly projections were little changed from those released in December.

Fed officials have at times over the past year acknowledged the risk of being forced to simultaneously fight two problems—financial instability and inflation. Several have said they would use emergency lending tools, along the lines of those unveiled this month, to stabilise credit markets so they could continue to raise interest rates or hold rates at higher levels to combat inflation.

At a news conference after the decision, Fed Chair Jerome Powell said officials had considered holding rates steady but opted to raise them given signs of still-high inflation and economic activity.

Various estimates of how much the banking stress could slow the economy amount to “guesswork, almost, at this point,” Mr. Powell said. “But we think it’s potentially quite real. And that argues for being alert as we go forward.”

That turmoil offers the strongest evidence yet of spillovers from higher interest rates to the broader economy. The upheaval has served as a stiff reminder of the perils Fed officials, regulators, lawmakers and the White House face trying to corral inflation that soared to a 40-year high last year.

U.S. policy makers cushioned the economic shock created by the Covid-19 pandemic in 2020 and 2021 by providing extensive financial aid and cheap money. Congress and the White House have largely delegated to the Fed the task of taming price pressures.

The fed-funds rate influences other borrowing costs throughout the economy, including rates on mortgages, credit cards and auto loans. The Fed has been raising rates to cool inflation by slowing economic growth. It believes those policy moves work through markets by tightening financial conditions, such as by raising borrowing costs or lowering prices of stocks and other assets.

Two weeks ago, Mr. Powell suggested officials would debate whether to raise rates by a quarter-point or a bigger half-point after reports showed hiring, spending and inflation were stronger early this year than they thought at the time of their Jan. 31-Feb. 1 meeting. “Nothing about the data suggests to me that we’ve tightened too much,” he said on March 7 before the Senate Banking Committee.

An astonishing run on the $200 billion Silicon Valley Bank changed everything. SVB’s depositors were heavily concentrated in the tight knit world of venture capital and startup firms, which were burning cash and withdrawing deposits as the once-highflying technology sector cooled.

On March 8, SVB said it was looking to raise capital from investors and that it would record a loss on longer-dated securities whose values had fallen as interest rates shot up. Nearly a quarter of the bank’s deposits fled over the next day and the bank was taken over by regulators on March 10.

To avoid a broader panic, federal authorities guaranteed the uninsured deposits of the California lender and a second institution, New York’s Signature Bank. The Fed also began offering loans of up to one year to banks on more generous terms as a precaution.

Banking-sector tremors are likely to lead to a pullback in lending because banks will face increased scrutiny from bank examiners and their own management teams to reduce risk taking. Banks could also see earnings squeezed if they feel pressure to raise deposit rates, which could further crimp lending.

That would mean fewer loans to consumers to buy cars, boats, homes and other big-ticket items, and less credit for businesses to hire, expand or invest, raising the risk of a steeper economic downturn.

Banks with fewer than $250 billion in assets account for roughly 50% of U.S. commercial and industrial lending, 60% of residential real estate lending, 80% of commercial real estate lending, and 45% of consumer lending, according to Goldman Sachs.

“I think we’re looking at a sizeable credit crunch,” said Daleep Singh, a former executive at the New York Fed who is now chief global economist at PGIM Fixed Income.

Since officials’ previous meeting, the economy had shown surprising strength, leading to concerns that aggressive rate rises over the previous year hadn’t done enough to slow the economy and lower inflation. Central bankers are concerned that prices will keep rising rapidly if consumers and businesses expect them to.

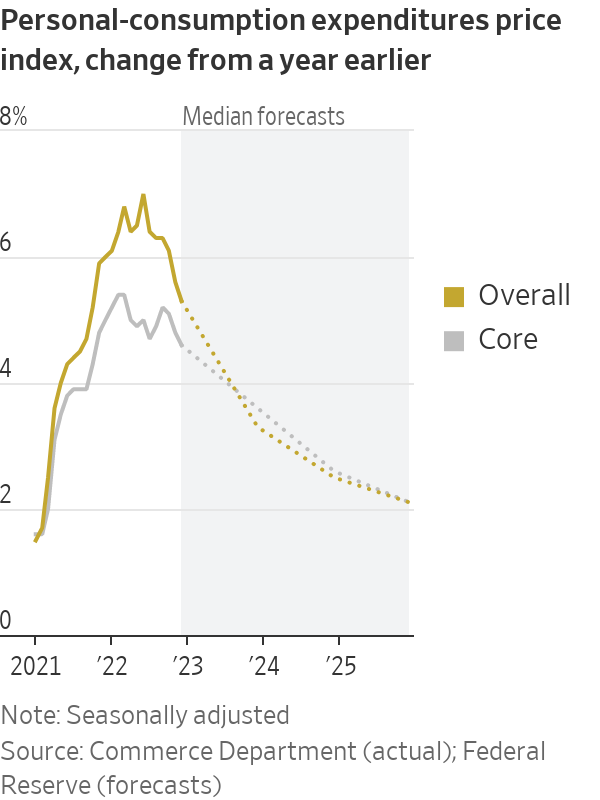

Inflation fell to 4.7% in January from 5.2% in September, as measured by the 12-month change in the personal-consumption expenditures price index excluding food and energy, the Fed’s preferred gauge. Economists expect the government to report next week that the inflation rate was unchanged in February.

Banking stress had led to questions in the past week over whether the Fed would even raise rates at all.

Some analysts fretted that a timeout on rate rises would risk so-called financial dominance, in which monetary policy becomes overly focused on avoiding market stress to the detriment of fighting inflation. A big market rally, in which stock prices rise and borrowing costs fall, could spur more demand and fan price pressures.

“They’d like to avoid that,” said William English, a former senior Fed economist who is a professor at Yale School of Management.

Others said the Fed would have been hard-pressed not to raise interest rates given recent strength in the economy and aggressive measures taken to shore up confidence in the banking system.

“Right now pausing would cause disruption,” said Donald Kohn, a former Fed vice chair. Deciding against raising rates would “signal that they don’t have confidence in their financial stability tools.”

Jan Hatzius, chief economist at Goldman Sachs, disagreed. It would have been better for the Fed to move cautiously given the highly uncertain environment that resulted from the banking stress, he said. “If more issues crop up after Wednesday, that’s also not going to be very confidence inspiring,” he said.

Fed officials have tried to signal their interest-rate moves deliberately over the past year to avoid the kind of market turmoil set off in 1994, when the Fed doubled its short-term benchmark rate from 3% to 6% in a 12-month span.

That rapid tightening hammered stocks and bonds and indirectly contributed to the demise of Kidder Peabody & Co., the bankruptcy of Orange County, Calif., and Mexico’s peso devaluation, which required a bailout from the U.S. and the International Monetary Fund.

After skipping on a rate increase in December 1994, as the peso crisis intensified, the Fed made a final rate increase in early 1995.

Copyright 2020, Dow Jones & Company, Inc. All Rights Reserved Worldwide. LEARN MORE

Copyright 2020, Dow Jones & Company, Inc. All Rights Reserved Worldwide. LEARN MORE

This stylish family home combines a classic palette and finishes with a flexible floorplan

Just 55 minutes from Sydney, make this your creative getaway located in the majestic Hawkesbury region.

Continued stagflation and cost of living pressures are causing couples to think twice about starting a family, new data has revealed, with long term impacts expected

Australia is in the midst of a ‘baby recession’ with preliminary estimates showing the number of births in 2023 fell by more than four percent to the lowest level since 2006, according to KPMG. The consultancy firm says this reflects the impact of cost-of-living pressures on the feasibility of younger Australians starting a family.

KPMG estimates that 289,100 babies were born in 2023. This compares to 300,684 babies in 2022 and 309,996 in 2021, according to the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS). KPMG urban economist Terry Rawnsley said weak economic growth often leads to a reduced number of births. In 2023, ABS data shows gross domestic product (GDP) fell to 1.5 percent. Despite the population growing by 2.5 percent in 2023, GDP on a per capita basis went into negative territory, down one percent over the 12 months.

“Birth rates provide insight into long-term population growth as well as the current confidence of Australian families,” said Mr Rawnsley. “We haven’t seen such a sharp drop in births in Australia since the period of economic stagflation in the 1970s, which coincided with the initial widespread adoption of the contraceptive pill.”

Mr Rawnsley said many Australian couples delayed starting a family while the pandemic played out in 2020. The number of births fell from 305,832 in 2019 to 294,369 in 2020. Then in 2021, strong employment and vast amounts of stimulus money, along with high household savings due to lockdowns, gave couples better financial means to have a baby. This led to a rebound in births.

However, the re-opening of the global economy in 2022 led to soaring inflation. By the start of 2023, the Australian consumer price index (CPI) had risen to its highest level since 1990 at 7.8 percent per annum. By that stage, the Reserve Bank had already commenced an aggressive rate-hiking strategy to fight inflation and had raised the cash rate every month between May and December 2022.

Five more rate hikes during 2023 put further pressure on couples with mortgages and put the brakes on family formation. “This combination of the pandemic and rapid economic changes explains the spike and subsequent sharp decline in birth rates we have observed over the past four years,” Mr Rawnsley said.

The impact of high costs of living on couples’ decision to have a baby is highlighted in births data for the capital cities. KPMG estimates there were 60,860 births in Sydney in 2023, down 8.6 percent from 2019. There were 56,270 births in Melbourne, down 7.3 percent. In Perth, there were 25,020 births, down 6 percent, while in Brisbane there were 30,250 births, down 4.3 percent. Canberra was the only capital city where there was no fall in the number of births in 2023 compared to 2019.

“CPI growth in Canberra has been slightly subdued compared to that in other major cities, and the economic outlook has remained strong,” Mr Rawnsley said. “This means families have not been hurting as much as those in other capital cities, and in turn, we’ve seen a stabilisation of births in the ACT.”

This stylish family home combines a classic palette and finishes with a flexible floorplan

Just 55 minutes from Sydney, make this your creative getaway located in the majestic Hawkesbury region.