Meet the CEOs Who Pull In More Than $100 Million a Year

Chief executives at Pinterest, Peloton and Hertz are outearning Apple’s Tim Cook—and hundreds of others leading bigger companies

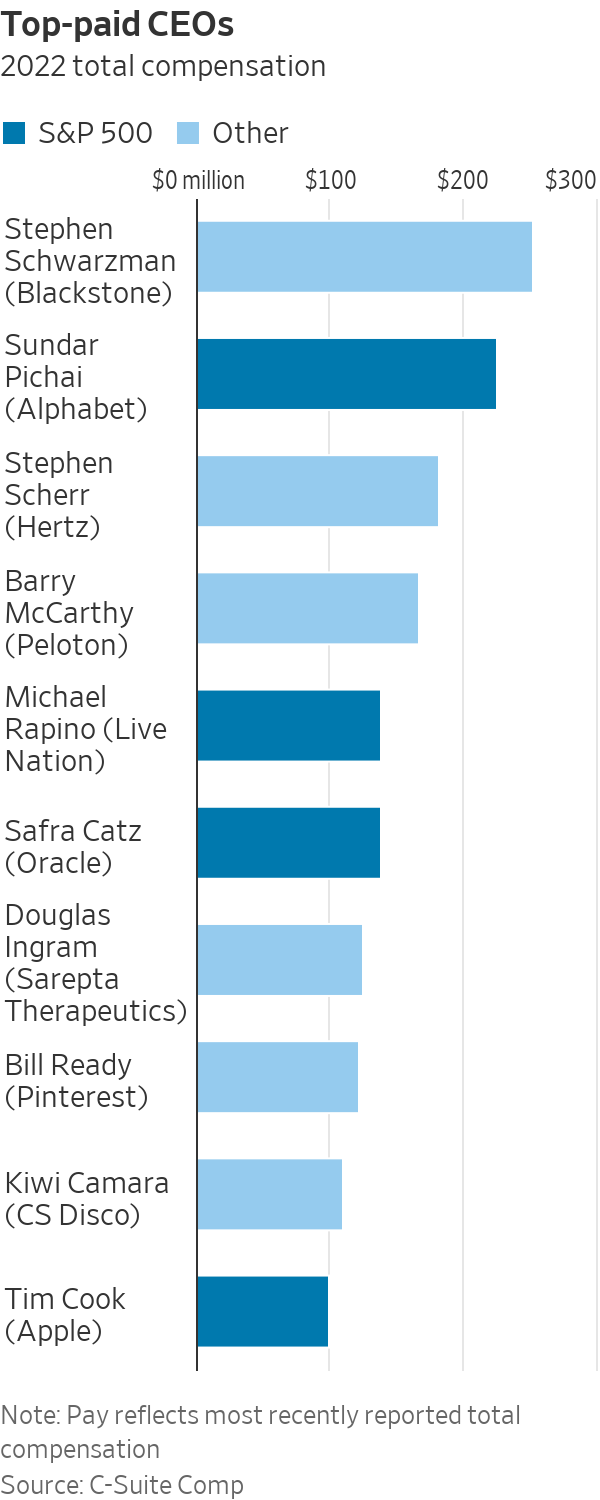

The highest-paid CEOs aren’t always the ones running the biggest companies.

The chief executives of Hertz, Peloton and Pinterest all earned more than $100 million in 2022, topping almost every CEO in the S&P 500 including Apple’s Tim Cook, who made $99 million. Also on that list: The man who runs CS Disco, a cloud-services provider that caters to attorneys and has a market capitalisation of about $500 million.

Six of the 10 highest-paid CEOs last year ran companies that weren’t in the S&P 500, according to C-Suite Comp, an executive-pay-data and analytics company. The S&P 500 comprises most of the biggest U.S. publicly traded companies.

Stephen Schwarzman of private-equity giant Blackstone earned the biggest pay package overall, at $253 million. Blackstone, larger than many S&P 500 companies at a market capitalisation of more than $100 billion, has a corporate structure similar to dual share-class setups that until recentlyhave kept other companies out of the index.

Schwarzman edged out Sundar Pichai, who runs Google parent Alphabet and received a pay package of $226 million—a total that put Pichai atop The Wall Street Journal’s annual CEO pay survey earlier this year. Pichai was followed in the earlier survey by Live Nation’s Michael Rapino, at $139 million.

Some executives in C-Suite Comp’s top-paid list, such as the leaders of Pinterest and Hertz, wouldn’t make the Journal’s annual pay ranking because those CEOs started during the year. The Journal’s analysis only ranks CEOs who served the full year.

Median pay for CEOs of S&P 500 companies slipped to $14.5 million last year, from $14.7 million the year before.

More broadly, nine CEOs made more than $100 million in 2022, of nearly 4,000 publicly traded U.S. companies in C-Suite Comp’s analysis. That is down from more than 20 a year earlier, as equity awards slimmed down, the firm said.

The bulk of CEO pay usually consists of restricted stock or options, the value of which can fluctuate. Many equity awards often only vest—becoming fully the executive’s property—if certain performance targets are met, or if the executive remains employed for a specified period.

For Schwarzman, Blackstone’s co-founder, about $190 million of his pay came in the form of carried interest and incentive-fee allocations. Carried interest refers to a cut of profit above a target that some investment managers receive. A further $58.8 million consisted of shares in real-estate investment trusts that Blackstone manages.

Schwarzman’s total pay was more than 50% larger than his 2021 package of $160 million. Total return for Blackstone shares, including the company’s dividend, was minus 40% last year, compared with minus 18% for the S&P 500. Through late June this year, Blackstone’s total return was 22%, compared with about 14% for the index.

Schwarzman owns almost 20% of Blackstone, a stake qualifying for dividends of about $1 billion in 2022.

A Blackstone spokesman said nearly 30% of Schwarzman’s 2022 pay reflects investment performance in 2021, in a period when the company’s share price also doubled. “Virtually all his compensation is carried interest and incentive fees—which are only paid when we deliver for our customers,” the spokesman said. He declined to say how much of Schwarzman’s pay was in cash.

At Hertz, Stephen Scherr’s total pay of $182 million included $3.4 million in salary and bonus. A further $178 million in restricted stock is structured to vest through 2026, much of it only if the company’s shares reach 90-day average price targets ranging up to nearly double its current share price.

In its annual proxy statement, Hertz said two price targets had already been met, meaning about $50 million in shares at recent prices stand to vest if Scherr stays employed through 2026, in addition to roughly $20 million that vested on Dec. 31.

Scherr, who earlier worked as Goldman Sachs Group’s chief financial officer, took Hertz’s top job in February 2022, about seven months after the rental-car chain emerged from bankruptcy-court protection.

Hertz shares fell 22% during Scherr’s tenure last year, while the S&P 500 fell 16%. The company valued Scherr’s equity award at roughly $128 million at year-end, securities filings show. Hertz shares were up about 20% this year through June 30.

A Hertz spokesman declined to comment beyond company disclosures.

Peloton’s Barry McCarthy started as CEO in February 2022, after stints as chief financial officer at Spotify and Netflix. His $168 million pay package at Peloton was almost entirely in stock options, which vest monthly over four years.

With Peloton trading near $7.50 in recent days, those eight million options are underwater, meaning they would cost more to exercise than the underlying shares are worth.

Peloton shares have fallen about 3% this year through June 30, and fell 79% in 2022 as declining demand left the company with a glut of the exercise bikes it sells.

Peloton representatives didn’t respond to requests for comment.

Of the $123 million Pinterest awarded Bill Ready last year, nearly $101 million came in stock options and $21.5 million in restricted stock made up most of the rest. Both were awarded in connection with his hiring as CEO in late June 2022.

The equity awards vest quarterly over four years if Ready remains employed. By year-end, Ready’s 2022 stock and option awards had increased in value to $153.6 million, Pinterest said in its securities filings.

Pinterest shares rose just over 20% last year. So far this year, Pinterest shares have risen about 13% through June 30.

A Pinterest spokeswoman said Ready isn’t expected to receive additional equity during his first four years, and the company sees his 2022 equity awards as the equivalent of about $30 million a year over that time. Ready also had to buy and hold $5 million in shares.

“If the company performs well, then Bill’s options have value,” the spokeswoman said. “If the company doesn’t perform well, then Bill’s compensation is going to be impacted.”

CS Disco, a 10-year-old Austin, Texas, company that sells online services to law firms, attorneys and legal-services companies, is the smallest company in the top-paid set. CEO Kiwi Camara, a co-founder, received $500,000 in salary plus stock options valued at $109 million, an award shareholders approved in a vote last year.

Camara’s options vest only if the company’s 90-day average share price reaches any of six targets through 2032, or if the company is acquired or Camara loses his job under certain circumstances.

Camara earned just under $1 million total in 2021, the year the company went public in late July. Its shares closed at $8.22 on Friday, up 30% for the year so far but down more than 75% from the company’s share price at the start of 2022.

CS Disco didn’t respond to requests for comment.

Copyright 2020, Dow Jones & Company, Inc. All Rights Reserved Worldwide. LEARN MORE

Copyright 2020, Dow Jones & Company, Inc. All Rights Reserved Worldwide. LEARN MORE

This stylish family home combines a classic palette and finishes with a flexible floorplan

Just 55 minutes from Sydney, make this your creative getaway located in the majestic Hawkesbury region.

Impact investing is becoming more mainstream as larger, institutional asset owners drive more money into the sector, according to the nonprofit Global Impact Investing Network in New York.

In the GIIN’s State of the Market 2024 report, published late last month, researchers found that assets allocated to impact-investing strategies by repeat survey responders grew by a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of 14% over the last five years.

These 71 responders to both the 2019 and 2024 surveys saw their total impact assets under management grow to US$249 billion this year from US$129 billion five years ago.

Medium- and large-size investors were largely responsible for the strong impact returns: Medium-size investors posted a median CAGR of 11% a year over the five-year period, and large-size investors posted a median CAGR of 14% a year.

Interestingly, the CAGR of assets held by small investors dropped by a median of 14% a year.

“When we drill down behind the compound annual growth of the assets that are being allocated to impact investing, it’s largely those larger investors that are actually driving it,” says Dean Hand, the GIIN’s chief research officer.

Overall, the GIIN surveyed 305 investors with a combined US$490 billion under management from 39 countries. Nearly three-quarters of the responders were investment managers, while 10% were foundations, and 3% were family offices. Development finance institutions, institutional asset owners, and companies represented most of the rest.

The majority of impact strategies are executed through private-equity, but public debt and equity have been the fastest-growing asset classes over the past five years, the report said. Public debt is growing at a CAGR of 32%, and public equity is growing at a CAGR of 19%. That compares to a CAGR of 17% for private equity and 7% for private debt.

According to the GIIN, the rise in public impact assets is being driven by larger investors, likely institutions.

Private equity has traditionally served as an ideal way to execute impact strategies, as it allows investors to select vehicles specifically designed to create a positive social or environmental impact by, for example, providing loans to smallholder farmers in Africa or by supporting fledging renewable energy technologies.

Future Returns: Preqin expects managers to rely on family offices, private banks, and individual investors for growth in the next six years

But today, institutional investors are looking across their portfolios—encompassing both private and public assets—to achieve their impact goals.

“Institutional asset owners are saying, ‘In the interests of our ultimate beneficiaries, we probably need to start driving these strategies across our assets,’” Hand says. Instead of carving out a dedicated impact strategy, these investors are taking “a holistic portfolio approach.”

An institutional manager may want to address issues such as climate change, healthcare costs, and local economic growth so it can support a better quality of life for its beneficiaries.

To achieve these goals, the manager could invest across a range of private debt, private equity, and real estate.

But the public markets offer opportunities, too. Using public debt, a manager could, for example, invest in green bonds, regional bank bonds, or healthcare social bonds. In public equity, it could invest in green-power storage technologies, minority-focused real-estate trusts, and in pharmaceutical and medical-care company stocks with the aim of influencing them to lower the costs of care, according to an example the GIIN lays out in a separate report on institutional strategies.

Influencing companies to act in the best interests of society and the environment is increasingly being done through such shareholder advocacy, either directly through ownership in individual stocks or through fund vehicles.

“They’re trying to move their portfolio companies to actually solving some of the challenges that exist,” Hand says.

Although the rate of growth in public strategies for impact is brisk, among survey respondents investments in public debt totaled only 12% of assets and just 7% in public equity. Private equity, however, grabs 43% of these investors’ assets.

Within private equity, Hand also discerns more evidence of maturity in the impact sector. That’s because more impact-oriented asset owners invest in mature and growth-stage companies, which are favored by larger asset owners that have more substantial assets to put to work.

The GIIN State of the Market report also found that impact asset owners are largely happy with both the financial performance and impact results of their holdings.

About three-quarters of those surveyed were seeking risk-adjusted, market-rate returns, although foundations were an exception as 68% sought below-market returns, the report said. Overall, 86% reported their investments were performing in line or above their expectations—even when their targets were not met—and 90% said the same for their impact returns.

Private-equity posted the strongest results, returning 17% on average, although that was less than the 19% targeted return. By contrast, public equity returned 11%, above a 10% target.

The fact some asset classes over performed and others underperformed, shows that “normal economic forces are at play in the market,” Hand says.

Although investors are satisfied with their impact performance, they are still dealing with a fragmented approach for measuring it, the report said. “Despite this, over two-thirds of investors are incorporating impact criteria into their investment governance documents, signalling a significant shift toward formalising impact considerations in decision-making processes,” it said.

Also, more investors are getting third-party verification of their results, which strengthens their accountability in the market.

“The satisfaction with performance is nice to see,” Hand says. “But we do need to see more about what’s happening in terms of investors being able to actually track both the impact performance in real terms as well as the financial performance in real terms.”

This stylish family home combines a classic palette and finishes with a flexible floorplan

Just 55 minutes from Sydney, make this your creative getaway located in the majestic Hawkesbury region.