Rising Interest Rates Mean Deficits Finally Matter

Investors ignored deficits when inflation was low. Now they are paying attention and getting worried.

The U.S. has long been the lender of last resort to the world. During the emerging-market panics of the 1990s, the global financial crisis of 2007-09 and the pandemic shutdown of 2020, it was the Treasury’s unmatched capacity to borrow that came to the rescue.

Now, the Treasury itself is a source of risk. No, the U.S. isn’t about to default or fail to sell enough bonds at its next auction. But the scale and upward trajectory of U.S. borrowing and absence of any political corrective now threaten markets and the economy in ways they haven’t for at least a generation.

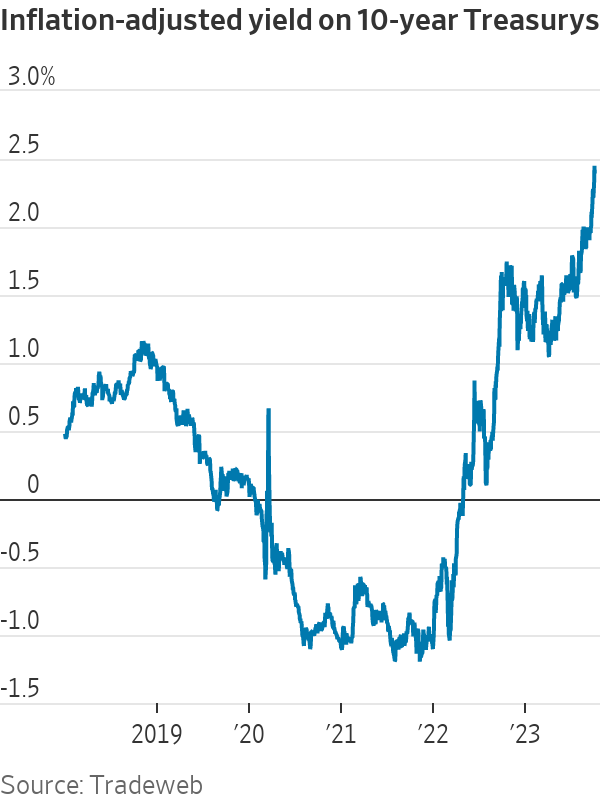

That’s the takeaway from the sudden sharp rise in Treasury yields in recent weeks. The usual suspects can’t explain it: The inflation picture has gotten marginally better, and the Federal Reserve has signalled it’s nearly done raising rates.

Instead, most of the increase is due to the part of yields, called the term premium, which has nothing to do with inflation or short-term rates. Numerous factors affect the term premium, and rising government deficits are a prime suspect.

Deficits have been wide for years. Why would they matter now? A better question might be: What took so long?

That larger deficits push up long-term rates had long been economic orthodoxy. But for the past 20 years, interest-rate models that incorporated fiscal policy didn’t work, noted Riccardo Trezzi, a former Fed economist who now runs his own research firm, Underlying Inflation.

That’s understandable. Central banks—worried about too-low inflation and stagnant growth—had kept interest rates around zero while buying up government bonds (“quantitative easing”). Private demand for credit was weak. This trumped any concern about deficits.

“We had a blissful 25 years of not having to worry about this problem,” said Mark Wiedman, senior managing director at BlackRock.

Today, though, central banks are worried about inflation being too high and have stopped buying and in some cases are shedding their bondholdings (“quantitative tightening”). Suddenly, fiscal policy matters again.

To paraphrase Hemingway, deficits can affect interest rates gradually or suddenly. Investors, asked to buy more bonds, gradually make room in their portfolios by buying less of something else, such as equities. Eventually, the risk-adjusted returns of these assets equalise, which means higher bond yields and lower price/earnings ratios on stocks. That has been happening for the past month.

Sometimes, though, markets can move suddenly, such as when Mexico threatened to default in 1994 and Greece did default a decade later. Even in countries that, unlike Mexico or Greece, borrow in currencies they control, interest rates can become hostage to deficits, such as in Canada in the early 1990s or Italy in the 1980s and early 1990s.

The U.S. isn’t Canada or Italy; it controls the world’s reserve currency, and its inflation and interest rates are mostly driven by domestic, not foreign, factors. On the other hand, the U.S. has also exploited those advantages to accumulate debt and run deficits that are much larger than those of peer economies.

There’s not much sign that this has yet imposed a penalty. Investors still project that the Fed will get inflation down to its 2% goal. At 2.4%, real (inflation-adjusted) Treasury yields are comparable to those in the mid-2000s and lower than in the 1990s, when the U.S. government’s debts and deficits were much lower.

Still, sometimes bad news accumulates below investors’ radar until something brings their collective attention to bear. Could a point come when “all the headlines will be about the fiscal unsustainability of the U.S.?” asked Wiedman. “I don’t hear this today from global investors. But do I think it could happen? Absolutely, that paradigm shift is possible. It’s not that no one shows up to buy Treasurys. It’s that they ask for a much higher yield.”

It’s notable that the recent rise in bond yields came as Fitch Ratings downgraded its U.S. credit rating, Treasury upped the size of its bond auctions, analysts began revising upward this year’s federal deficit, and Congress nearly shut down parts of the government over a failure to pass spending bills.

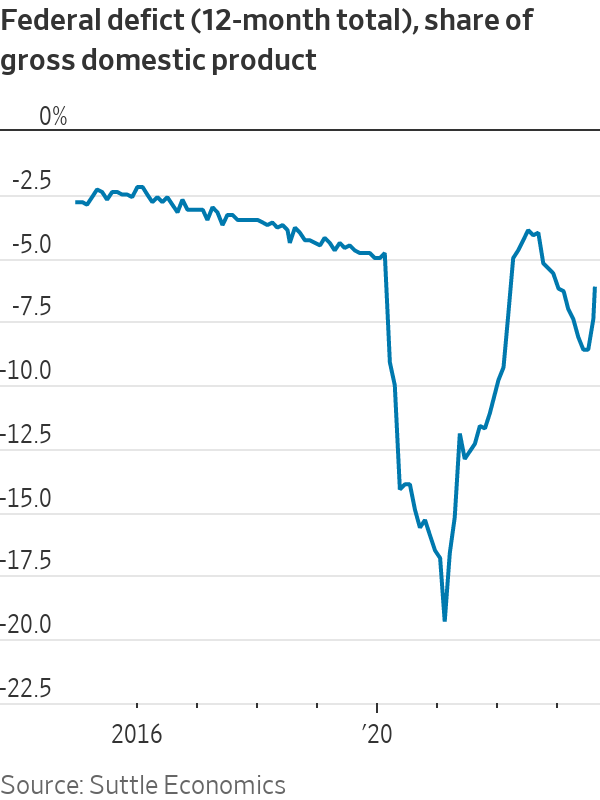

The federal deficit was over 7% of gross domestic product in fiscal 2023, after adjusting for accounting distortions related to student debt, Barclays analysts noted last week. That’s larger than any deficit since 1930 outside of wars and recessions. And this is occurring at a time of low unemployment and strong economic growth, suggesting that in normal times, “deficits may be much higher,” Barclays added.

Abroad, fiscal policy has clearly begun to matter. Last fall, a proposed U.K. tax cut triggered a surge in British bond yields; the government scrapped the proposal, then resigned. Italian yields have risen since the government last week delayed reducing its deficit to below European guidelines. Trezzi said that for the past decade the European Central Bank had bought more than 100% of net Italian government bond issuance, but that’s coming to an end.

Foreign investors, worried about inflation and deficits, have been selling Italian bonds, while Italian households have been buying, Trezzi said. “With a weakening economy, it is unclear for how long…households can offset the selloff of foreigners.”

Investors looking for U.S. political will to rein in deficits would take note that both former President Donald Trump and President Biden, their parties’ front-runners for the 2024 presidential nomination, have signed deficit-busting legislation and that both of their parties have pledged not to cut the two largest spending programs, Medicare and Social Security, or raise taxes on most households.

They would also notice that the Republican speaker of the House of Representatives was just ousted by rebels in his own party because he had passed a bipartisan spending bill to prevent the government from shutting down. True, the rebels wanted less spending. But shutdowns, Barclays noted, represent “erosion of governance.” This isn’t how a country trying to reassure the bond market acts.

Copyright 2020, Dow Jones & Company, Inc. All Rights Reserved Worldwide. LEARN MORE

Copyright 2020, Dow Jones & Company, Inc. All Rights Reserved Worldwide. LEARN MORE

This stylish family home combines a classic palette and finishes with a flexible floorplan

Just 55 minutes from Sydney, make this your creative getaway located in the majestic Hawkesbury region.

Continued stagflation and cost of living pressures are causing couples to think twice about starting a family, new data has revealed, with long term impacts expected

Australia is in the midst of a ‘baby recession’ with preliminary estimates showing the number of births in 2023 fell by more than four percent to the lowest level since 2006, according to KPMG. The consultancy firm says this reflects the impact of cost-of-living pressures on the feasibility of younger Australians starting a family.

KPMG estimates that 289,100 babies were born in 2023. This compares to 300,684 babies in 2022 and 309,996 in 2021, according to the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS). KPMG urban economist Terry Rawnsley said weak economic growth often leads to a reduced number of births. In 2023, ABS data shows gross domestic product (GDP) fell to 1.5 percent. Despite the population growing by 2.5 percent in 2023, GDP on a per capita basis went into negative territory, down one percent over the 12 months.

“Birth rates provide insight into long-term population growth as well as the current confidence of Australian families,” said Mr Rawnsley. “We haven’t seen such a sharp drop in births in Australia since the period of economic stagflation in the 1970s, which coincided with the initial widespread adoption of the contraceptive pill.”

Mr Rawnsley said many Australian couples delayed starting a family while the pandemic played out in 2020. The number of births fell from 305,832 in 2019 to 294,369 in 2020. Then in 2021, strong employment and vast amounts of stimulus money, along with high household savings due to lockdowns, gave couples better financial means to have a baby. This led to a rebound in births.

However, the re-opening of the global economy in 2022 led to soaring inflation. By the start of 2023, the Australian consumer price index (CPI) had risen to its highest level since 1990 at 7.8 percent per annum. By that stage, the Reserve Bank had already commenced an aggressive rate-hiking strategy to fight inflation and had raised the cash rate every month between May and December 2022.

Five more rate hikes during 2023 put further pressure on couples with mortgages and put the brakes on family formation. “This combination of the pandemic and rapid economic changes explains the spike and subsequent sharp decline in birth rates we have observed over the past four years,” Mr Rawnsley said.

The impact of high costs of living on couples’ decision to have a baby is highlighted in births data for the capital cities. KPMG estimates there were 60,860 births in Sydney in 2023, down 8.6 percent from 2019. There were 56,270 births in Melbourne, down 7.3 percent. In Perth, there were 25,020 births, down 6 percent, while in Brisbane there were 30,250 births, down 4.3 percent. Canberra was the only capital city where there was no fall in the number of births in 2023 compared to 2019.

“CPI growth in Canberra has been slightly subdued compared to that in other major cities, and the economic outlook has remained strong,” Mr Rawnsley said. “This means families have not been hurting as much as those in other capital cities, and in turn, we’ve seen a stabilisation of births in the ACT.”

This stylish family home combines a classic palette and finishes with a flexible floorplan

Just 55 minutes from Sydney, make this your creative getaway located in the majestic Hawkesbury region.