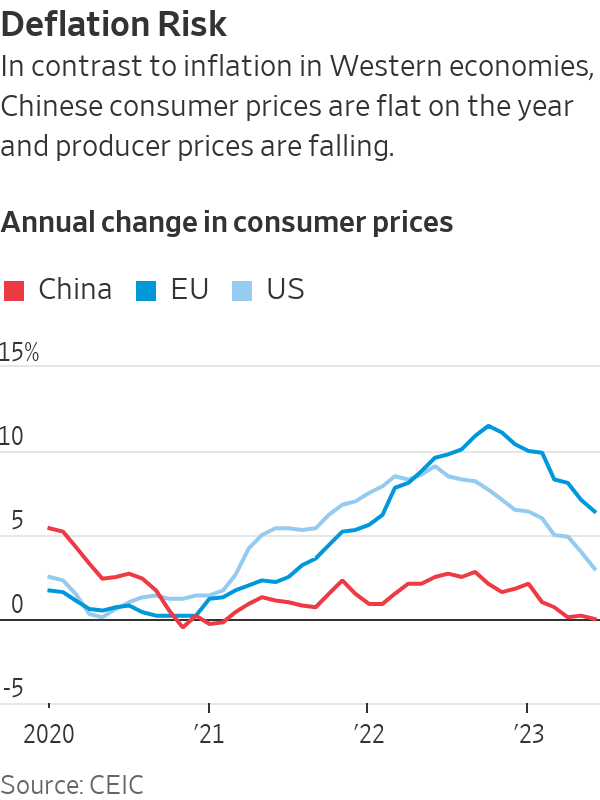

While Everyone Else Fights Inflation, China Deflation Fears Deepen

Some economists see parallels between China and Japan, where growth stagnated and prices fell for years

Signs of deflation are becoming more prevalent across China, heaping extra pressure on Beijing to reignite growth or risk falling into an economic trap it could find hard to escape.

While the rest of the world tussles with inflation, China is at risk of experiencing a prolonged spell of falling prices that—if it takes root—could eat into corporate profits, sap consumer spending and push more people out of work. Its effects would ripple across the globe, easing prices for some products that countries like the U.S. buy from China, but would also deprive the world of important Chinese demand for raw materials and consumer goods, while also creating other problems.

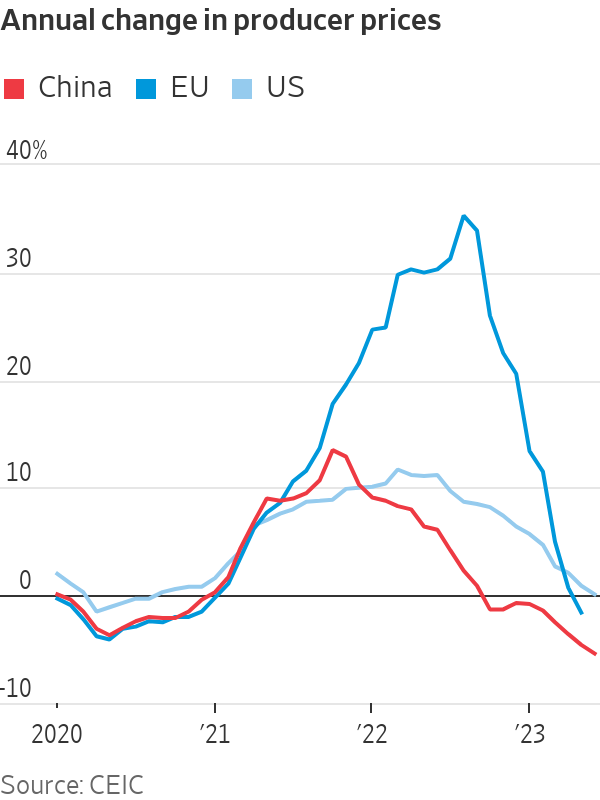

Prices charged by Chinese factories that make products ranging from steel to cement to chemicals have been falling for months. Consumer prices, meanwhile, have gone flat, with prices for certain goods—including sugar, eggs, clothes and household appliances—now falling on a month-over-month basis amid weak demand.

Most economists think China will probably avoid a deep and lasting period of deflation. Its economy is growing, albeit sluggishly, and the government has unveiled a variety of small stimulus measures that could help more. Earlier in July, Liu Guoqiang, a Chinese central bank official, dismissed concerns that China is slipping toward deflation.

But some economists see alarming parallels between China’s current predicament and the experience of Japan, which struggled for years with deflation and stagnant growth.

In the 1990s, a collapse in stock markets and real-estate values in Japan pushed companies and households to drastically cut back spending to service burdensome debts—a so-called balance-sheet recession that some see taking shape in China today.

Data released Thursday showed industrial profits are sinking and average new home sale prices fell in June.

If China were to tip into protracted deflation, it has another big problem: Traditional methods of fighting it are either unpopular in Beijing, or lack potency due to the country’s heavy debt load and other issues. Beijing is wary of large deficit-financed spending programs that could juice growth and push prices higher, while big debts mean consumers and businesses are reluctant to borrow and spend.

“The big concern is whether the policy tools that they have will have much traction in terms of trying to avert deflation, or deal with deflationary pressures once they arrive,” said Eswar Prasad, a professor of trade policy and economics at Cornell University and a former head of the International Monetary Fund’s China division.

For the global economy, extended deflation in China might help cool inflation elsewhere, including the U.S., since its factories make up such a large share of the world’s goods.

However, a flood of cut-price Chinese exports on global markets could squeeze out rival exporters in some countries, hurting jobs and investment in those economies. Chinese export prices for steel and chemicals fell by about a third over the 12 months through June.

A deflationary spell in China would also likely mean weaker Chinese demand for food, energy and raw materials, which big chunks of the world rely on for export earnings.

“The market is underestimating the deflationary impact on the global economy,” said Frederic Neumann, chief Asia economist at HSBC in Hong Kong.

Consumer prices in the U.S. rose 3% in June from a year earlier, a sharp slowdown from the 8% annual rate a year earlier but still above the 2% rate targeted by the Federal Reserve. Annual inflation in the European Union last month was 6.4% as the region continues to feel the squeeze from high energy and food prices.

In China, annual consumer-price inflation in June was zero. Producer prices fell in China last month by 5.4% from a year earlier.

Subdued consumer spending is one big reason. Some idiosyncratic factors are also at play, including a steep rise last year in the price of pork—a staple in the Chinese diet—that hasn’t been repeated.

But weak price pressures are also a payback of sorts for China’s experience during the Covid-19 pandemic, when exports rocketed thanks to Western demand for gym equipment, home improvement supplies and other goods.

The demand surge helped push Chinese producer prices up 12% between the start of 2020 and their peak in April last year, according to an index calculated by Moody’s Analytics.

When governments lifted lockdowns and Western demand eased, the trend reversed. Producer prices began falling on a year-over-year basis in October and have kept falling every month since.

Chinese factories, which expanded to meet Western demand during the pandemic, now face overcapacity. The hope was that Chinese consumers would step into the breach and soak up excess inventories as export markets dried up. But that hasn’t happened, and as more businesses pivot toward selling into the domestic market, the downward pressure on prices is building.

With global energy and food prices also weaker than before, economists expect overall consumer prices in China to stay nearly flat, or even fall, in the coming months. In addition to many foodstuffs and clothing items, prices have also been falling for electric vehicles, as Chinese automakers and Tesla have slashed prices amid slower sales growth and in an effort to win more share in a crowded market.

China could escape further deflation if growth regains momentum later this year, helped by government stimulus, as some economists anticipate. Nomura economists expect annual consumer-price inflation in China of negative 0.2% in the third quarter, with inflation eventually turning positive again toward the end of the year.

The risk for China is that deflation proves more persistent than expected. Falling prices tend to squeeze spending as consumers await a better deal tomorrow, reinforcing a downward spiral.

The longer it lasts, the more severe its effects become. Entrenched deflation means debts become harder to bear as profits and incomes fall. Companies shed workers to fatten shrinking margins.

In Shanghai, Liu Wang has held off on plans to upgrade his apartment because he is worried about sinking more money into a property whose value he believes could keep dropping.

“The economic condition is highly uncertain now,” said Liu, who works at a logistics firm that is shifting its focus toward domestic business after its export business weakened. In his hometown of Qufu in China’s northeastern Shandong province, demand for homes has been tepid despite a drop in prices, he said.

“The housing bubble is still quite large,” Liu added. “I don’t see any reason why prices will go up.”

In Japan, deflation first appeared in 1995. Excluding a few respites, it more or less stuck around until the 2008-09 financial crisis. Even today, Japan is battling to sustain higher rates of price growth with ultraloose central bank policies.

One textbook response is a massive monetary expansion, lowering interest rates and printing money to spur borrowing and spending, which in theory should trigger more inflation.

But data show Chinese companies are reluctant to take on new debt to expand production, while droves of homeowners are choosing to repay mortgages early. Both are signs of weak demand for loans, muffling the effectiveness of interest-rate cuts.

A major reason is that many companies and households already have such large debts that they don’t want to add more. Household debt has surged to 1.5 times that of income, far above the level of most developed countries, including the U.S., according to calculations by Jens Presthus, associate director of Global Counsel, an advisory firm.

Deflation, or even just the fear of deflation, can make the problem worse. Borrowers worry the cost of servicing their debts is going to rise, so they respond by saving more and spending less.

“Deflation is particularly dangerous when there’s a lot of debt,” said Arthur Budaghyan, chief emerging markets economist at BCA Research.

Copyright 2020, Dow Jones & Company, Inc. All Rights Reserved Worldwide. LEARN MORE

Copyright 2020, Dow Jones & Company, Inc. All Rights Reserved Worldwide. LEARN MORE

This stylish family home combines a classic palette and finishes with a flexible floorplan

Just 55 minutes from Sydney, make this your creative getaway located in the majestic Hawkesbury region.

Continued stagflation and cost of living pressures are causing couples to think twice about starting a family, new data has revealed, with long term impacts expected

Australia is in the midst of a ‘baby recession’ with preliminary estimates showing the number of births in 2023 fell by more than four percent to the lowest level since 2006, according to KPMG. The consultancy firm says this reflects the impact of cost-of-living pressures on the feasibility of younger Australians starting a family.

KPMG estimates that 289,100 babies were born in 2023. This compares to 300,684 babies in 2022 and 309,996 in 2021, according to the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS). KPMG urban economist Terry Rawnsley said weak economic growth often leads to a reduced number of births. In 2023, ABS data shows gross domestic product (GDP) fell to 1.5 percent. Despite the population growing by 2.5 percent in 2023, GDP on a per capita basis went into negative territory, down one percent over the 12 months.

“Birth rates provide insight into long-term population growth as well as the current confidence of Australian families,” said Mr Rawnsley. “We haven’t seen such a sharp drop in births in Australia since the period of economic stagflation in the 1970s, which coincided with the initial widespread adoption of the contraceptive pill.”

Mr Rawnsley said many Australian couples delayed starting a family while the pandemic played out in 2020. The number of births fell from 305,832 in 2019 to 294,369 in 2020. Then in 2021, strong employment and vast amounts of stimulus money, along with high household savings due to lockdowns, gave couples better financial means to have a baby. This led to a rebound in births.

However, the re-opening of the global economy in 2022 led to soaring inflation. By the start of 2023, the Australian consumer price index (CPI) had risen to its highest level since 1990 at 7.8 percent per annum. By that stage, the Reserve Bank had already commenced an aggressive rate-hiking strategy to fight inflation and had raised the cash rate every month between May and December 2022.

Five more rate hikes during 2023 put further pressure on couples with mortgages and put the brakes on family formation. “This combination of the pandemic and rapid economic changes explains the spike and subsequent sharp decline in birth rates we have observed over the past four years,” Mr Rawnsley said.

The impact of high costs of living on couples’ decision to have a baby is highlighted in births data for the capital cities. KPMG estimates there were 60,860 births in Sydney in 2023, down 8.6 percent from 2019. There were 56,270 births in Melbourne, down 7.3 percent. In Perth, there were 25,020 births, down 6 percent, while in Brisbane there were 30,250 births, down 4.3 percent. Canberra was the only capital city where there was no fall in the number of births in 2023 compared to 2019.

“CPI growth in Canberra has been slightly subdued compared to that in other major cities, and the economic outlook has remained strong,” Mr Rawnsley said. “This means families have not been hurting as much as those in other capital cities, and in turn, we’ve seen a stabilisation of births in the ACT.”

This stylish family home combines a classic palette and finishes with a flexible floorplan

Just 55 minutes from Sydney, make this your creative getaway located in the majestic Hawkesbury region.