Why New Technology Is So Stressful at Work—and What to Do About It

Anxiety over technological change is escalating, especially thanks to AI. Researchers and therapists offer all sorts of ways to deal with it.

When Ben Plomion took his latest job, he learned quickly that his tech skills were behind the times.

At 46, he’s a decade or two older than most of his co-workers—and he’s used to an earlier generation of software. While he was accustomed to presentation programs like PowerPoint or Google Slides, for instance, his young colleagues were working with an app called Canva.

“I went in all reluctantly, because I had to relearn everything I’d learned for the last 10 years,” he says.

Plomion—chief marketing officer for a Los Angeles startup that works with crypto technology—is no Luddite. But he sometimes felt overwhelmed by the pace of change. Then came ChatGPT, and thousands of other artificial-intelligence apps. “Where do you start? What tool do you pick? And you’re almost frozen by uncertainty and doubt and indecision,” he says.

Anxiety over technological change on the job has long plagued workplaces—perhaps never more so than today, as AI potentially threatens to upend everything. The questions are familiar ones: Will people be able to keep their skills up-to-date? How will their jobs change as tech advances? Perhaps most stressful of all: Will new technology replace them? All of the uncertainty and stress can foster frustration, insecurity or self-blame that can affect their work and personal lives, and even their health.

Fortunately, researchers have studied this phenomenon for decades, gleaning insights into the deep psychological roots of these fears, how they affect people’s response to technology—and how both workers and companies can mitigate the stress.

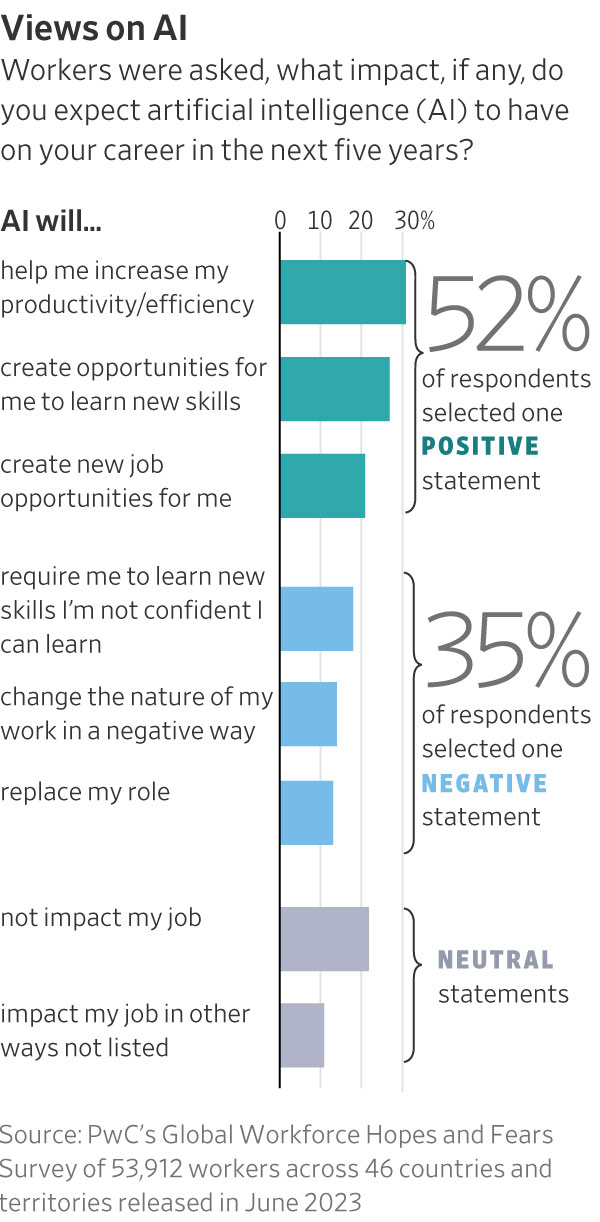

To get an idea of just how high tech-induced anxiety is, consider PwC’s 2022 Global Workforce Hopes and Fears Survey, conducted before the widespread popularity of generative AI tech like ChatGPT. The report found that 30% of over 50,000 workers were concerned about technology replacing their role within three years, and 39% said they weren’t getting enough tech training at work.

In this year’s survey (released in June), 35% had some negative concerns about AI, such as fears that the technology will take their job, affect their role or require skills they might not be able to learn. They aren’t imagining the possible turmoil. A March global study by Goldman Sachs estimated that generative AI “could expose the equivalent of 300 [million] full-time jobs to automation,” although the report says that most jobs in the U.S. would be altered by AI, but not be replaced.

Workers who are worried about AI are more likely to report feeling tense or stressed at work, a new survey from the American Psychological Association found. “It can cause a person to be almost in a fight or flight state, where then every perceived threat to their job carries this heightened sense of urgency and concern,” says Dennis Stolle, one of the lead authors.

Lessons from psychology

The roots of the fear can go back to primal feelings—an instinctive, evolutionary apprehension of anything novel, says Ofir Turel, a professor of information systems at the University of Melbourne. “Our ancestors were threatened by new species…new animals, new tribes moving to their territories,” he says.

New technologies can cause insecurity, even from something as minor as disrupting people’s routines. “Our brains are designed to maintain the status quo,” says Nicole Lipkin, a clinical and organisational psychologist in Philadelphia. “We’re designed to get from A to Z as efficiently as possible. And that means keeping things the same.”

Sophia Xepoleas, a tech PR strategist in Oakland, recalls her reluctance to take time out to learn the project-management application Asana. “It is…a new pathway in your brain that you’re training,” she says. “And the ones that are already working are working real hard.”

But the sense of threat from technology can go even deeper, by menacing people’s personal identity, says Varun Grover, a professor of information technology at the University of Arkansas.

One aspect of that identity is people’s sense of professional competence, and hard-to-learn technology can threaten that. New tech can also threaten people’s sense of identity in the professional role they fill, he says, if it changes their job duties or workplace power dynamics.

Turel found this happening with the introduction of electronic medical records to a Midwestern hospital in a 2020 study. “They threatened physicians and nurses,” he says. “They were the people who actually control the information. Now you have to spend time to go through 10 screens when you prescribe something.”

This resulted in what researchers called “unfaithful use” of the new tech. Medical personnel would skip over screens or enter random information just to get through the forms. Turel and other work-stress researchers have another term for this reaction: sabotage.

The latest artificial intelligence takes this identity threat much further, says Grover, because it promises to do the higher-level reasoning that people think of as uniquely human.

Running away

To be sure, rarely does tech stress reach a clinical level of anxiety or depression. Even so, it can lead to unhealthy behaviour.

For instance, a natural response to stress is to run away from the threatening technology. “When there’s lots of uncertainty, then it’s a little bit difficult to cope,” says Mindy Shoss, professor of industrial/organisational psychology at the University of Central Florida. “And people tend to do what we call emotion-focused coping strategies, which include things like avoidance,” she says.

In tech, this could mean refusing to learn or use a new piece of software and trying to continue with the older application you are used to.

To help work through this anxiety, say researchers, people can use tools from psychological practices such as cognitive behavioural therapy, which can help people challenge negative thought patterns.

For instance, when people face new, difficult technology, it “can be a huge trigger for negative self-talk,” a sense that we lack ability or aren’t trying hard enough, says Vaile Wright, senior director for healthcare innovation at the American Psychological Association.

Instead, people can start with understanding why they find the new technology upsetting and re-evaluating the sense of risk and threat.

Workers can also reframe a technology challenge in such a way to realise the situation isn’t so bad (for instance, you won’t get fired if you don’t master this new tech). Other times, it helps them accept genuine misfortune (you will lose your job) and strategise how to move on.

It can also help for workers to give themselves some credit for facing challenges.

“It could be a thought like, ‘It’s not that surprising that this is hard. I didn’t go to school for this. But I’ve overcome hard things before,’ ” says Wright.

These tools work best in a therapeutic setting, but they are also available in self-help workbooks, says Wright. She suggests, for instance, checking out “The Dialectical Behavior Therapy Skills Workbook” or recommendations from the Association for Behavioral and Cognitive Therapies.

Resisting or embracing

Another danger is what psychologists call catastrophising. “Examples of cognitive distortions are [saying,] ‘If I don’t learn this within a week, I’m going to get fired.’ That’s catastrophising or all-or-none thinking,” says Lipkin.

Reframing is one way Xepoleas reduces the all-or-nothing pressure surrounding tech: She doesn’t need to master every new piece of technology to get benefits from it. Plomion, meanwhile, reduces stress by telling himself he’s doing everything he needs to do to get his job done. “I am never going to be a ChatGPT expert,” he says. “There’s a lot of people who can do that. But at a minimum…I know how to use the tools.”

The two have also tried reframing new tech as an opportunity. Xepoleas admits that, after fighting the Asana app, she ultimately found it helpful. “I’ll usually take the initiative on myself,” she says, “especially if it’s something that’s important for me to learn, or if I don’t learn it, I’m going to miss out on something strategic or important.”

People can also benefit from distraction—a cognitive behavioural technique for breaking the cycle of anxious thoughts. Xepoleas enjoys visiting a park and listening to classical music, as a respite during or after the workday. Plomion goes surfing most mornings. “When I get back from the ocean and go straight to the office after that, I’m a lot more relaxed,” he says. “I’m also a lot more eager to go back to my AI tools and learn them.”

Plomion is also an ardent skateboarder and considers mastering new tricks as akin to figuring out technology. This is known as “building mastery” in dialectical behavioural therapy, a cousin of cognitive behavioural therapy, says Wright. Achievements in one activity build confidence for taking on other challenges.

It might seem daunting to be constructively positive about new tech—but it is certainly possible. While about a third of the PwC survey respondents expressed fear over new tech, about half expected positive scenarios, such as AI making them more productive or creating new job opportunities. (The Goldman Sachs AI report, meanwhile, anticipates a boost to the global economy and sees AI taking a complementary role in many jobs, not replacing people.)

Reframing disappointment

Reframing is also crucial when the worst is true. While people often exaggerate threats, they are not always wrong. They might lose their jobs because of technology, after all. And even if they keep them, technology may change their roles in ways they don’t like—fears that are accelerating because of AI.

It can be healthy to acknowledge feelings of loss—for a time. That is the thrust of acceptance and commitment therapy, or ACT. Instead of trying to debunk the problem underlying their anxiety, “ACT therapy would have a person accept the experience,” says David Blustein, a professor of counselling psychology at Boston College.

A related concept, from dialectical behavioural therapy, is radical acceptance. People don’t have to approve of a situation that causes grief and pain, but fighting reality instead of accepting it leads to more grief and pain. “Sometimes I just have to give in, and I have to say, OK, this is going to be a part of my life now,” says Grover. “So how do I reconceptualise my role identity with this technology in my life?”

How employers can help

During times of anxiety, companies can foster a sense of agency among employees by bringing them early into the conversation about new technologies—finding out what they need and if the tools on offer will do the trick.

It is all right if these conversations include some complaining, says Lipkin, the Philadelphia psychologist. “When I hear you gripe, I’m getting what you’re afraid of,” she says. But raising concerns is only the beginning of the process. Employees should be encouraged to spend most of the discussion finding solutions to the problems, she says.

Workers can also help each other cope with disruptive tech by discussing their frustrations, says Shoss, as it provides validation of their feelings, reassurance and a sense of camaraderie. On a practical level, co-workers can help each other figure out new technologies. “Most younger people, at least in my company, and probably many others, are very willing to share their expertise in a specific tool,” says Plomion.

That’s no substitute for formal employee training, though, because employers should articulate an overall plan for how the technology is meant to be used. Employers also have to recognise different types of learning that work for each employee, says Wright, and provide multiple options, such as written tutorials, videos and one-on-one sessions.

“Employers really need to prioritise their employees’ mental health,” she says. “We know that when our mental health and our emotional well-being [are] more stable, we’re actually better employees. We’re more committed to the organisation.”

Copyright 2020, Dow Jones & Company, Inc. All Rights Reserved Worldwide. LEARN MORE

Copyright 2020, Dow Jones & Company, Inc. All Rights Reserved Worldwide. LEARN MORE

This stylish family home combines a classic palette and finishes with a flexible floorplan

Just 55 minutes from Sydney, make this your creative getaway located in the majestic Hawkesbury region.

Continued stagflation and cost of living pressures are causing couples to think twice about starting a family, new data has revealed, with long term impacts expected

Australia is in the midst of a ‘baby recession’ with preliminary estimates showing the number of births in 2023 fell by more than four percent to the lowest level since 2006, according to KPMG. The consultancy firm says this reflects the impact of cost-of-living pressures on the feasibility of younger Australians starting a family.

KPMG estimates that 289,100 babies were born in 2023. This compares to 300,684 babies in 2022 and 309,996 in 2021, according to the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS). KPMG urban economist Terry Rawnsley said weak economic growth often leads to a reduced number of births. In 2023, ABS data shows gross domestic product (GDP) fell to 1.5 percent. Despite the population growing by 2.5 percent in 2023, GDP on a per capita basis went into negative territory, down one percent over the 12 months.

“Birth rates provide insight into long-term population growth as well as the current confidence of Australian families,” said Mr Rawnsley. “We haven’t seen such a sharp drop in births in Australia since the period of economic stagflation in the 1970s, which coincided with the initial widespread adoption of the contraceptive pill.”

Mr Rawnsley said many Australian couples delayed starting a family while the pandemic played out in 2020. The number of births fell from 305,832 in 2019 to 294,369 in 2020. Then in 2021, strong employment and vast amounts of stimulus money, along with high household savings due to lockdowns, gave couples better financial means to have a baby. This led to a rebound in births.

However, the re-opening of the global economy in 2022 led to soaring inflation. By the start of 2023, the Australian consumer price index (CPI) had risen to its highest level since 1990 at 7.8 percent per annum. By that stage, the Reserve Bank had already commenced an aggressive rate-hiking strategy to fight inflation and had raised the cash rate every month between May and December 2022.

Five more rate hikes during 2023 put further pressure on couples with mortgages and put the brakes on family formation. “This combination of the pandemic and rapid economic changes explains the spike and subsequent sharp decline in birth rates we have observed over the past four years,” Mr Rawnsley said.

The impact of high costs of living on couples’ decision to have a baby is highlighted in births data for the capital cities. KPMG estimates there were 60,860 births in Sydney in 2023, down 8.6 percent from 2019. There were 56,270 births in Melbourne, down 7.3 percent. In Perth, there were 25,020 births, down 6 percent, while in Brisbane there were 30,250 births, down 4.3 percent. Canberra was the only capital city where there was no fall in the number of births in 2023 compared to 2019.

“CPI growth in Canberra has been slightly subdued compared to that in other major cities, and the economic outlook has remained strong,” Mr Rawnsley said. “This means families have not been hurting as much as those in other capital cities, and in turn, we’ve seen a stabilisation of births in the ACT.”

This stylish family home combines a classic palette and finishes with a flexible floorplan

Just 55 minutes from Sydney, make this your creative getaway located in the majestic Hawkesbury region.