Why Prices of the World’s Most Expensive Handbags Keep Rising

Designers are charging more for their most recognisable bags to maintain the appearance of exclusivity as the industry balloons

The price of a basic Hermès Birkin handbag has jumped $1,000. This first-world problem for fashionistas is a sign that luxury brands are playing harder to get with their most sought-after products.

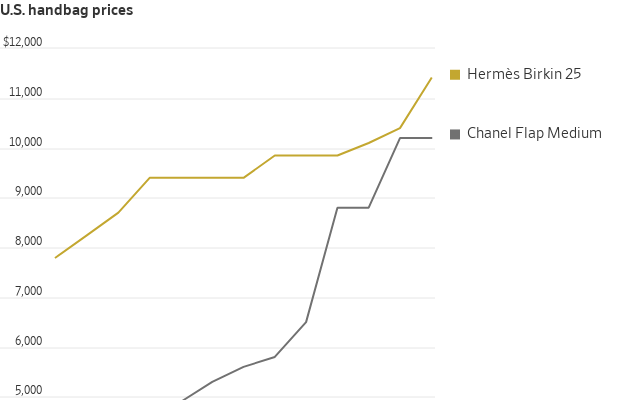

Hermès recently raised the cost of a basic Birkin 25-centimeter handbag in its U.S. stores by 10% to $11,400 before sales tax, according to data from luxury handbag forum PurseBop. Rarer Birkins made with exotic skins such as crocodile have jumped more than 20%. The Paris brand says it only increases prices to offset higher manufacturing costs, but this year’s increase is its largest in at least a decade.

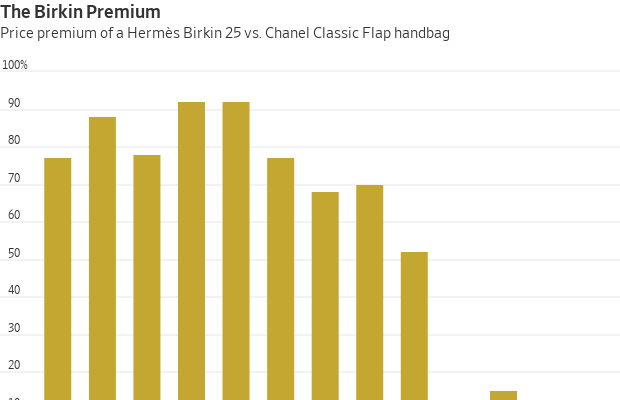

The brand may feel under pressure to defend its reputation as the maker of the world’s most expensive handbags. The “Birkin premium”—the price difference between the Hermès bag and its closest competitor , the Chanel Classic Flap in medium—shrank from 70% in 2019 to 2% last year, according to PurseBop founder Monika Arora. Privately owned Chanel has jacked up the price of its most popular handbag by 75% since before the pandemic.

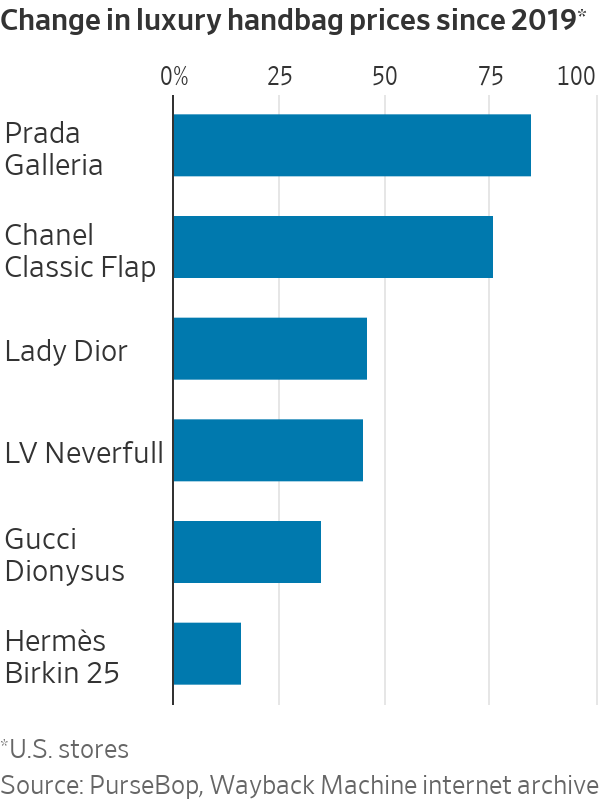

Eye-watering price increases on luxury brands’ benchmark products are a wider trend. Prada ’s Galleria bag will set shoppers back a cool $4,600—85% more than in 2019, according to the Wayback Machine internet archive. Christian Dior ’s Lady Dior bag and the Louis Vuitton Neverfull are both 45% more expensive, PurseBop data show.

With the U.S. consumer-price index up a fifth since 2019, luxury brands do need to offset higher wage and materials costs. But the inflation-beating increases are also a way to manage the challenge presented by their own success: how to maintain an aura of exclusivity at the same time as strong sales.

Luxury brands have grown enormously in recent years, helped by the Covid-19 lockdowns, when consumers had fewer outlets for spending. LVMH ’s fashion and leather goods division alone has almost doubled in size since 2019, with €42.2 billion in sales last year, equivalent to $45.8 billion at current exchange rates. Gucci, Chanel and Hermès all make more than $10 billion in sales a year. One way to avoid overexposure is to sell fewer items at much higher prices.

Many aspirational shoppers can no longer afford the handbags, but luxury brands can’t risk alienating them altogether. This may explain why labels such as Hermès and Prada have launched makeup lines and Gucci’s owner Kering is pushing deeper into eyewear. These cheaper categories can be a kind of consolation prize. They can also be sold in the tens of millions without saturating the market.

“Cosmetics are invisible—unless you catch someone applying lipstick and see the logo, you can’t tell the brand,” says Luca Solca, luxury analyst at Bernstein.

Most of the luxury industry’s growth in 2024 will come from price increases. Sales are expected to rise by 7% this year, according to Bernstein estimates, even as brands only sell 1% to 2% more stuff.

Limiting volume growth this way only works if a brand is so popular that shoppers won’t balk at climbing prices and defect to another label. Some companies may have pushed prices beyond what consumers think they are worth. Sales of Prada’s handbags rose a meagre 1% in its last quarter and the group’s cheaper sister label Miu Miu is growing faster.

Ramping up prices can invite unflattering comparisons. At more than $2,000, Burberry ’s small Lola bag is around 40% more expensive today than it was a few years ago. Luxury shoppers may decide that tried and tested styles such as Louis Vuitton’s Neverfull bag, which is now a little cheaper than the Burberry bag, are a better buy—especially as Louis Vuitton bags hold their value better in the resale market.

Aggressive price increases can also drive shoppers to secondhand websites. If a barely used Prada Galleria bag in excellent condition can be picked up for $1,500 on luxury resale website The Real Real, it is less appealing to pay three times that amount for the bag brand new.

The strategy won’t help everyone, but for the best luxury brands, stretching the price spectrum can keep the risks of growth in check.

Copyright 2020, Dow Jones & Company, Inc. All Rights Reserved Worldwide. LEARN MORE

Copyright 2020, Dow Jones & Company, Inc. All Rights Reserved Worldwide. LEARN MORE

This stylish family home combines a classic palette and finishes with a flexible floorplan

Just 55 minutes from Sydney, make this your creative getaway located in the majestic Hawkesbury region.

Continued stagflation and cost of living pressures are causing couples to think twice about starting a family, new data has revealed, with long term impacts expected

Australia is in the midst of a ‘baby recession’ with preliminary estimates showing the number of births in 2023 fell by more than four percent to the lowest level since 2006, according to KPMG. The consultancy firm says this reflects the impact of cost-of-living pressures on the feasibility of younger Australians starting a family.

KPMG estimates that 289,100 babies were born in 2023. This compares to 300,684 babies in 2022 and 309,996 in 2021, according to the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS). KPMG urban economist Terry Rawnsley said weak economic growth often leads to a reduced number of births. In 2023, ABS data shows gross domestic product (GDP) fell to 1.5 percent. Despite the population growing by 2.5 percent in 2023, GDP on a per capita basis went into negative territory, down one percent over the 12 months.

“Birth rates provide insight into long-term population growth as well as the current confidence of Australian families,” said Mr Rawnsley. “We haven’t seen such a sharp drop in births in Australia since the period of economic stagflation in the 1970s, which coincided with the initial widespread adoption of the contraceptive pill.”

Mr Rawnsley said many Australian couples delayed starting a family while the pandemic played out in 2020. The number of births fell from 305,832 in 2019 to 294,369 in 2020. Then in 2021, strong employment and vast amounts of stimulus money, along with high household savings due to lockdowns, gave couples better financial means to have a baby. This led to a rebound in births.

However, the re-opening of the global economy in 2022 led to soaring inflation. By the start of 2023, the Australian consumer price index (CPI) had risen to its highest level since 1990 at 7.8 percent per annum. By that stage, the Reserve Bank had already commenced an aggressive rate-hiking strategy to fight inflation and had raised the cash rate every month between May and December 2022.

Five more rate hikes during 2023 put further pressure on couples with mortgages and put the brakes on family formation. “This combination of the pandemic and rapid economic changes explains the spike and subsequent sharp decline in birth rates we have observed over the past four years,” Mr Rawnsley said.

The impact of high costs of living on couples’ decision to have a baby is highlighted in births data for the capital cities. KPMG estimates there were 60,860 births in Sydney in 2023, down 8.6 percent from 2019. There were 56,270 births in Melbourne, down 7.3 percent. In Perth, there were 25,020 births, down 6 percent, while in Brisbane there were 30,250 births, down 4.3 percent. Canberra was the only capital city where there was no fall in the number of births in 2023 compared to 2019.

“CPI growth in Canberra has been slightly subdued compared to that in other major cities, and the economic outlook has remained strong,” Mr Rawnsley said. “This means families have not been hurting as much as those in other capital cities, and in turn, we’ve seen a stabilisation of births in the ACT.”

This stylish family home combines a classic palette and finishes with a flexible floorplan

Just 55 minutes from Sydney, make this your creative getaway located in the majestic Hawkesbury region.