America’s Billionaires Love Japanese Stocks. Why Don’t the Japanese?

Japan’s government wants cash-hoarding households to invest more

TOKYO—Japan’s government is on a mission to make buying stocks hot again.

Many of America’s biggest investors are bullish on Japan. Warren Buffett shared that he increased his investments in Japanese companies during an April visit to the country. Ken Griffin is preparing to reopen an office in Tokyo for his hedge fund, Citadel, and investment banks Goldman Sachs and Morgan Stanley have issued optimistic outlooks for Japan’s stock market.

Japan’s problem is this: There are few signs its estimated 125 million residents share in the excitement.

Burned by dismal returns since the bursting of Japan’s asset bubble in the late 1980s and early 1990s, generations of families here have stashed most of their money in low-yielding savings accounts rather than trying to increase their wealth through the stock market.

Japanese households put an average of just 11% of their savings into stocks and 54% in cash and bank deposits, according to Bank of Japan data released last month. That trails well behind the U.S., where households have about 39% of their money tied up in the market and only 13% in cash and bank deposits, according to Federal Reserve data.

Haruyo Arai, a 62-year-old office worker, began investing in the stock market just last month.

“I was brought up by parents who would say, ‘Don’t dabble in stocks,’ ” she said.

Japanese Prime Minister Fumio Kishida has pledged to double households’ asset incomes, in part by encouraging people to invest in risky assets like stocks. The government is raising caps for Japan’s tax-exempt investment system for small investors, the Nippon Individual Savings Account, with changes set to take effect in January. The Tokyo Stock Exchange has been urging companies to boost their valuations and increase shareholder returns.

Arai cited the upcoming expansion to NISA, along with a desire to save more money for the future, as some of the reasons she decided to begin taking investing more seriously. She has been taking weekend classes at Tokyo-based Financial Academy to learn more about stocks and waking up early every morning to watch a TV news program focused on the economy.

Some believe investors like Arai will prove to be the exception, not the rule. Stocks here haven’t hit a record in decades. There isn’t much buzz among ordinary people about investing in Japanese markets.

“I’ve got the impression that Japanese people don’t really think positively about the desire to make money,” said Takashi Kawaguchi, a 48-year-old office worker who, like Arai, has been learning about investing at Financial Academy.

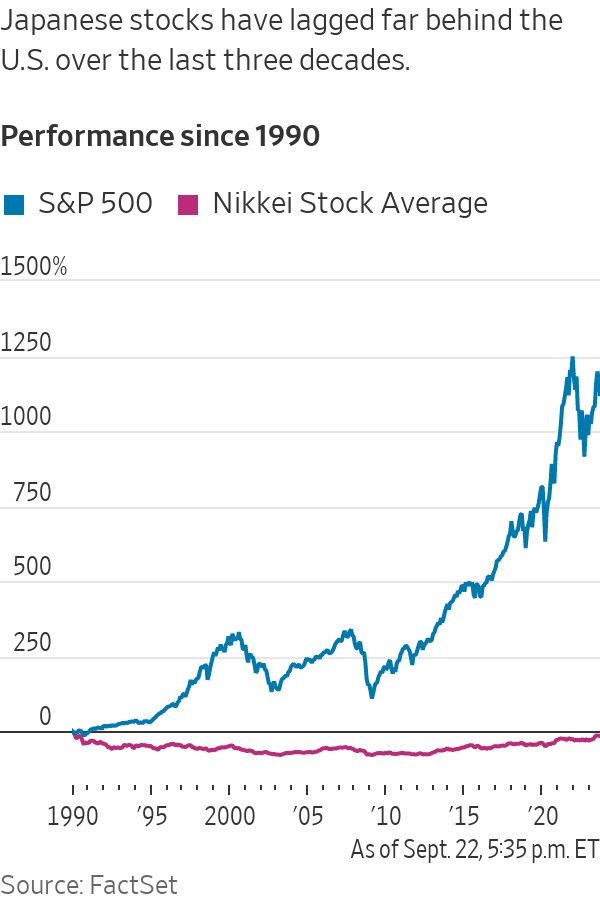

While the 2023 rally has helped lift Japanese stock indexes to 33-year highs, long-term returns pale in comparison to what an investor would have gotten by investing in U.S. stocks. The Nikkei closed at 32,402 on Friday, still 17% below its record hit in 1989. The S&P 500 has grown more than twelvefold over that time. That has made many investors here turn to foreign markets instead of focusing their bets within Japan.

“The Nikkei might hit 40,000, god knows when,” said Heihachiro “Hutch” Okamoto, foreign equity consultant at retail brokerage Monex. “But most of our investors prefer U.S. stocks.”

To Okamoto’s point, the most popular names traded on Monex daily aren’t Japanese stock indexes like the Topix or Nikkei, brand-name companies like Sony or even the “sogo shosha”—the trading houses that Buffett has invested in. Instead, they are all American names: companies like Nvidia, Tesla, Apple and Amazon.com, as well as funds tracking the S&P 500 and the Nasdaq-100.

And that is just among those interested in investing in the first place. While in past years, everyday investors in Japan made a name for themselves with their forays into the foreign exchange market, the overall trading culture here has been one of hesitation.

“Most people here think investing is very risky,” said Hidekazu Ishida, a special adviser at FinCity.Tokyo, which works with the government and the financial industry to try to boost investment in Tokyo. Being into finance comes off as “kakkowarui,” he added, referencing a word for uncool.

Even some heads of companies are lukewarm about the idea of encouraging more individual investors to buy Japanese stocks.

“I’m neutral about that,” said Takeshi Niinami, chief executive officer of whisky and beverage giant Suntory, when asked if he thought it would be a good idea for more Japanese people to invest in the market. Stock investing is risky, he said. And many Japanese people remain wary of participating in the market, because of the severity of prior downturns.

“I think perhaps increasing interest rates is better for people,” he said.

—Chieko Tsuneoka and Alastair Gale contributed to this article

Copyright 2020, Dow Jones & Company, Inc. All Rights Reserved Worldwide. LEARN MORE

Copyright 2020, Dow Jones & Company, Inc. All Rights Reserved Worldwide. LEARN MORE

This stylish family home combines a classic palette and finishes with a flexible floorplan

Just 55 minutes from Sydney, make this your creative getaway located in the majestic Hawkesbury region.

Continued stagflation and cost of living pressures are causing couples to think twice about starting a family, new data has revealed, with long term impacts expected

Australia is in the midst of a ‘baby recession’ with preliminary estimates showing the number of births in 2023 fell by more than four percent to the lowest level since 2006, according to KPMG. The consultancy firm says this reflects the impact of cost-of-living pressures on the feasibility of younger Australians starting a family.

KPMG estimates that 289,100 babies were born in 2023. This compares to 300,684 babies in 2022 and 309,996 in 2021, according to the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS). KPMG urban economist Terry Rawnsley said weak economic growth often leads to a reduced number of births. In 2023, ABS data shows gross domestic product (GDP) fell to 1.5 percent. Despite the population growing by 2.5 percent in 2023, GDP on a per capita basis went into negative territory, down one percent over the 12 months.

“Birth rates provide insight into long-term population growth as well as the current confidence of Australian families,” said Mr Rawnsley. “We haven’t seen such a sharp drop in births in Australia since the period of economic stagflation in the 1970s, which coincided with the initial widespread adoption of the contraceptive pill.”

Mr Rawnsley said many Australian couples delayed starting a family while the pandemic played out in 2020. The number of births fell from 305,832 in 2019 to 294,369 in 2020. Then in 2021, strong employment and vast amounts of stimulus money, along with high household savings due to lockdowns, gave couples better financial means to have a baby. This led to a rebound in births.

However, the re-opening of the global economy in 2022 led to soaring inflation. By the start of 2023, the Australian consumer price index (CPI) had risen to its highest level since 1990 at 7.8 percent per annum. By that stage, the Reserve Bank had already commenced an aggressive rate-hiking strategy to fight inflation and had raised the cash rate every month between May and December 2022.

Five more rate hikes during 2023 put further pressure on couples with mortgages and put the brakes on family formation. “This combination of the pandemic and rapid economic changes explains the spike and subsequent sharp decline in birth rates we have observed over the past four years,” Mr Rawnsley said.

The impact of high costs of living on couples’ decision to have a baby is highlighted in births data for the capital cities. KPMG estimates there were 60,860 births in Sydney in 2023, down 8.6 percent from 2019. There were 56,270 births in Melbourne, down 7.3 percent. In Perth, there were 25,020 births, down 6 percent, while in Brisbane there were 30,250 births, down 4.3 percent. Canberra was the only capital city where there was no fall in the number of births in 2023 compared to 2019.

“CPI growth in Canberra has been slightly subdued compared to that in other major cities, and the economic outlook has remained strong,” Mr Rawnsley said. “This means families have not been hurting as much as those in other capital cities, and in turn, we’ve seen a stabilisation of births in the ACT.”

This stylish family home combines a classic palette and finishes with a flexible floorplan

Just 55 minutes from Sydney, make this your creative getaway located in the majestic Hawkesbury region.