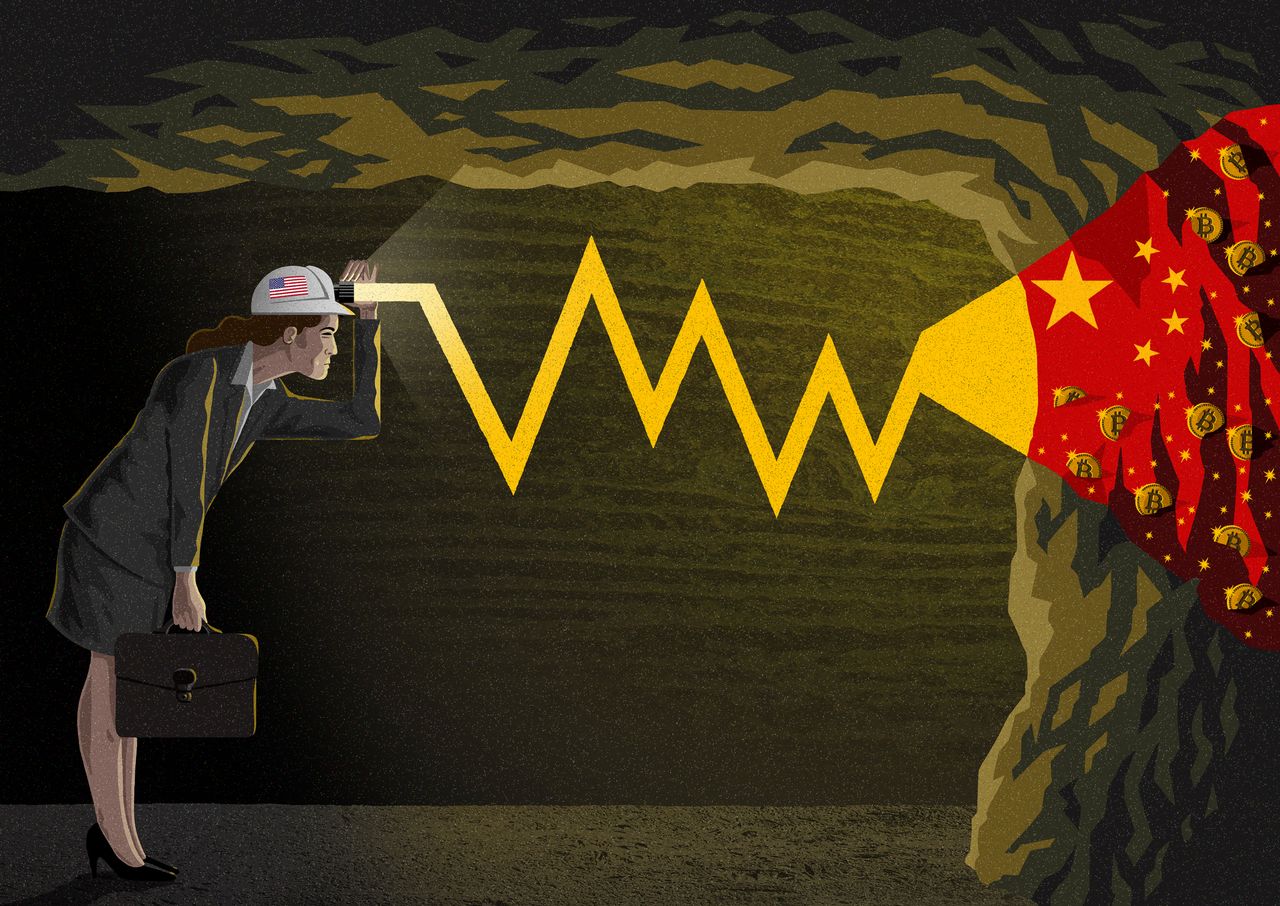

Bitcoin Mining Is Big in China. Why Investors Should Worry.

Why the digital currency’s dependence on China, specifically Xinjiang, is concerning.

Critics of the nearly ubiquitous digital currency Bitcoin often focus on its environmental consequences. After Tesla announced recently that it had bought roughly US$1.5 billion in Bitcoin, sending the cryptocurrency’s value skyrocketing, sustainability investors decried the “level of carbon dioxide emissions generated from Bitcoin mining.” Certainly, “mining”—the energy-intensive process by which computers solve complex algorithmic problems to verify blockchain transactions, for which they’re rewarded in digital currency—is an undeniable environmental offender.

But there is another worrying aspect of Bitcoin, one that should make investors think twice about including it as part of an ethical investing strategy.

A large amount of new Bitcoin comes from Xinjiang, the region in northwest China where more than a million Uighur Muslims and other minorities have been imprisoned in concentration camps. According to the Cambridge Bitcoin Electricity Consumption Index, as of April 2020, China was responsible for 65% of all Bitcoin mining. And of that, 36% takes place in Xinjiang, the largest regional component. Why? Cheap coal means cheap energy to power the machines that mine Bitcoin. Xinjiang has an abundant supply of coal, and the region’s relative remoteness means that it’s far cheaper to use the resource locally than move it to other parts of China. The issue is not that the Chinese government uses forced labour in Xinjiang coal mines—the reporting on that is inconclusive. Rather, because of the atrocities occurring in Xinjiang, any product produced there brings with it high ethical and regulatory risk.

In the camps—which Beijing calls “vocational educational and training centres”—guards try to “deradicalise” Uighurs for crimes such as wearing long dresses, abstaining from pork or alcohol, or praying. While the difficulty of reporting in the region means that concrete evidence is scarce, camp survivors have described systemic torture, forced sterilization, and rape. (Beijing denies committing atrocities.) In January, right before leaving office, Secretary of State Mike Pompeo declared that Beijing was committing “genocide” in the region. His successor, Antony Blinken, agrees.

To summarize: Roughly 20% of new Bitcoin is mined in Xinjiang, the site of some of the world’s most egregious human-rights abuses.

Today, Bitcoin’s association with Xinjiang is barely discussed. But that may change. For public-facing funds considering investing in the notoriously volatile asset, there are two other risks to consider. The first is that because of the concern among the American public about human-rights abuses in Xinjiang, holding assets tied to the region comes at the risk of a public relations disaster.

Already, activists have criticised Olympic sponsors for participating in the “genocide Olympics”—the 2022 Beijing Winter Games. Multiyear campaigns to hive Xinjiang off from the global supply chain are already well under way.

In July, more than 190 organizations, including the AFL-CIO, called for clothing brands to end all sourcing from Xinjiang within the next 12 months. (In 2020, roughly 20% of the world’s cotton came from Xinjiang.) It’s not hard to imagine Bitcoin becoming another frontier in their campaigns.

Investors should be alert for regulatory action. Bitcoin’s Xinjiang relationship gives ammunition to those in the U.S. government who may want to further monitor or restrict the transactions. Analysts expect the Biden administration to pay close attention to Bitcoin. In mid-February, Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen criticised the “misuse” of cryptocurrencies in laundering money or funding terrorism. At the same time, Bitcoin’s Xinjiang connection could put it on the radar of the various arms of the Commerce, State, and Defense departments that are seeking to reduce U.S. dependence on physical and digital Chinese goods. If this trend intensifies, the Treasury Department could sanction the Bitcoin mining firms that have large operations in Xinjiang, or issue advisories that it is “studying” Bitcoin’s links to the region—signalling to global financial institutions another risk of holding the cryptocurrency.

In January, U.S. Customs banned the imports of Xinjiang cotton and tomato products and told U.S. companies to get forced labour out of their supply chains. Extricating Bitcoin from Xinjiang could be far more difficult. Unlike, say, blood diamonds or Iranian crude oil, Bitcoins exist only digitally. While there is a public record of the billions of Bitcoin transactions, it’s exceedingly complicated to determine the geographic origin of a particular Bitcoin. That means all Bitcoin holders can deny any connection to human-rights abuses—but also risk being tarnished by the association.

It has long been ironic that Bitcoin, developed to decentralize power, is so dependent on China, a country ruled by a government obsessed with centralizing it. But depending on China is one thing. Depending on Xinjiang is another. There are many excellent ethical and regulatory reasons not to buy Bitcoin. Add Xinjiang to that list.

Isaac Stone Fish is the CEO and founder of Strategy Risks, a firm that quantifies corporate exposure to China.>

Copyright 2020, Dow Jones & Company, Inc. All Rights Reserved Worldwide. LEARN MORE

Copyright 2020, Dow Jones & Company, Inc. All Rights Reserved Worldwide. LEARN MORE

This stylish family home combines a classic palette and finishes with a flexible floorplan

Just 55 minutes from Sydney, make this your creative getaway located in the majestic Hawkesbury region.

Continued stagflation and cost of living pressures are causing couples to think twice about starting a family, new data has revealed, with long term impacts expected

Australia is in the midst of a ‘baby recession’ with preliminary estimates showing the number of births in 2023 fell by more than four percent to the lowest level since 2006, according to KPMG. The consultancy firm says this reflects the impact of cost-of-living pressures on the feasibility of younger Australians starting a family.

KPMG estimates that 289,100 babies were born in 2023. This compares to 300,684 babies in 2022 and 309,996 in 2021, according to the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS). KPMG urban economist Terry Rawnsley said weak economic growth often leads to a reduced number of births. In 2023, ABS data shows gross domestic product (GDP) fell to 1.5 percent. Despite the population growing by 2.5 percent in 2023, GDP on a per capita basis went into negative territory, down one percent over the 12 months.

“Birth rates provide insight into long-term population growth as well as the current confidence of Australian families,” said Mr Rawnsley. “We haven’t seen such a sharp drop in births in Australia since the period of economic stagflation in the 1970s, which coincided with the initial widespread adoption of the contraceptive pill.”

Mr Rawnsley said many Australian couples delayed starting a family while the pandemic played out in 2020. The number of births fell from 305,832 in 2019 to 294,369 in 2020. Then in 2021, strong employment and vast amounts of stimulus money, along with high household savings due to lockdowns, gave couples better financial means to have a baby. This led to a rebound in births.

However, the re-opening of the global economy in 2022 led to soaring inflation. By the start of 2023, the Australian consumer price index (CPI) had risen to its highest level since 1990 at 7.8 percent per annum. By that stage, the Reserve Bank had already commenced an aggressive rate-hiking strategy to fight inflation and had raised the cash rate every month between May and December 2022.

Five more rate hikes during 2023 put further pressure on couples with mortgages and put the brakes on family formation. “This combination of the pandemic and rapid economic changes explains the spike and subsequent sharp decline in birth rates we have observed over the past four years,” Mr Rawnsley said.

The impact of high costs of living on couples’ decision to have a baby is highlighted in births data for the capital cities. KPMG estimates there were 60,860 births in Sydney in 2023, down 8.6 percent from 2019. There were 56,270 births in Melbourne, down 7.3 percent. In Perth, there were 25,020 births, down 6 percent, while in Brisbane there were 30,250 births, down 4.3 percent. Canberra was the only capital city where there was no fall in the number of births in 2023 compared to 2019.

“CPI growth in Canberra has been slightly subdued compared to that in other major cities, and the economic outlook has remained strong,” Mr Rawnsley said. “This means families have not been hurting as much as those in other capital cities, and in turn, we’ve seen a stabilisation of births in the ACT.”

This stylish family home combines a classic palette and finishes with a flexible floorplan

Just 55 minutes from Sydney, make this your creative getaway located in the majestic Hawkesbury region.