China Tried Using Economic Ties to Bring Taiwan Closer. It Isn’t Working.

As geopolitical tensions rise, Taiwan is shifting its economy to rely more on the U.S. and other countries but at a cost

TAIPEI—For years, Beijing hoped to win control of Taiwan by convincing its people their economic futures were inextricably tied to China.

Instead, more Taiwanese businesses are pivoting to the U.S. and other markets, reducing the island democracy’s dependence on China and angering Beijing as it sees its economic leverage over Taiwan ebb.

In one sign of the shift, the U.S. replaced mainland China as the top buyer of Taiwanese agricultural products for the first time last year.

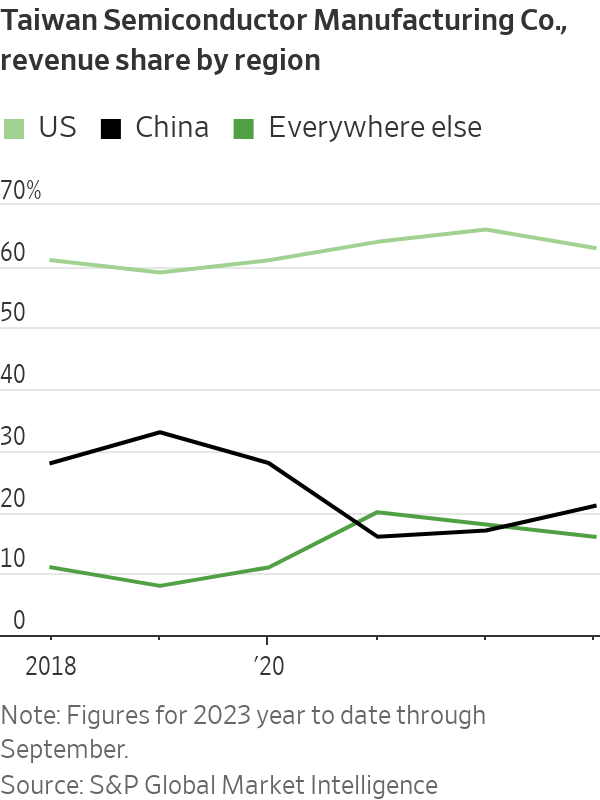

Electronics firms such as chip maker Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co. are also selling more goods to American and other non-Chinese buyers, thanks in part to Washington’s chip restrictions and Apple’s bets on Taiwanese chips.

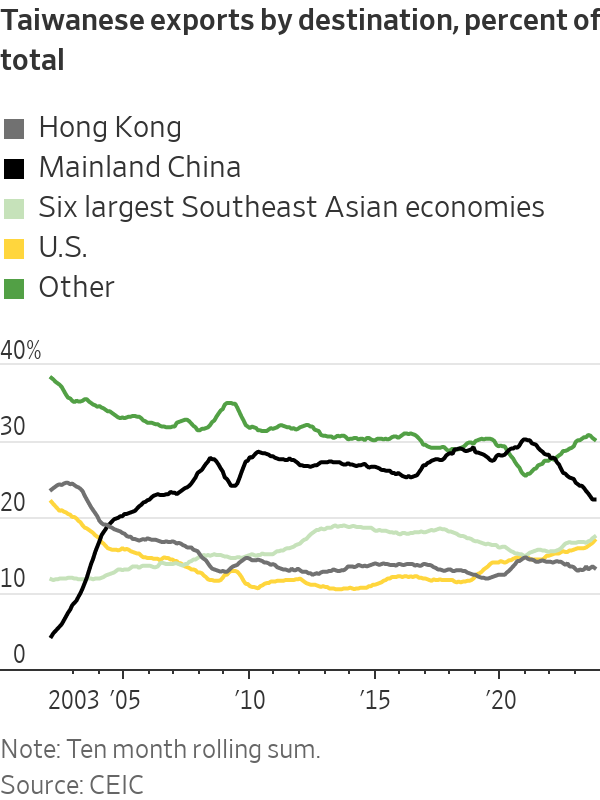

Overall, Taiwanese exports to the U.S. in the first 10 months of 2023 were more than 80% higher than in the same period of 2018, Taiwanese government data shows. Taiwanese exports to the mainland were 1% lower—a major change from a decade or so ago when China’s and Taiwan’s economies were rapidly integrating.

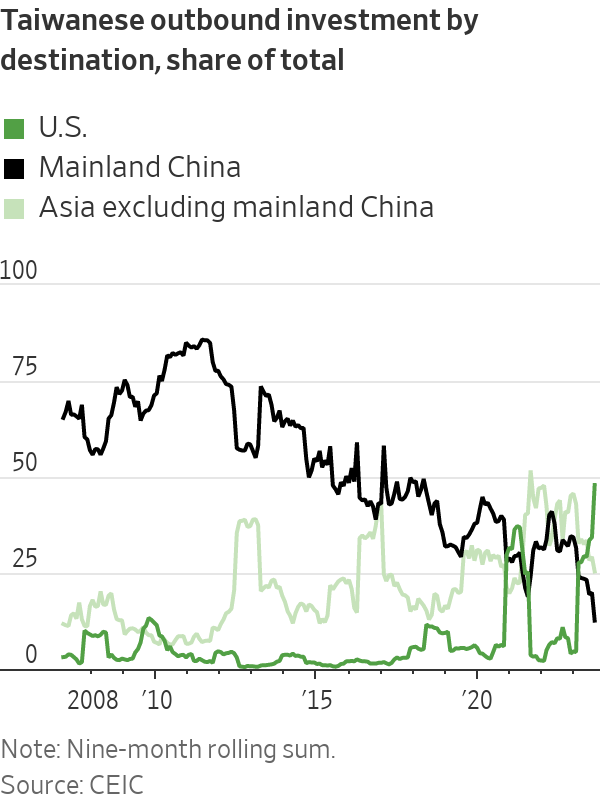

Taiwan’s outbound investment has also shifted. After flowing mostly to mainland China in the early 2000s, it has now moved decisively toward other destinations, including Southeast Asia, India and the U.S.

Taiwanese electronics giant Foxconn, which assembles iPhones in mainland China, is expanding in India and Vietnam after Apple began pushing its suppliers to diversify.

Chinese state media recently reported that China had opened tax and land-use probes into Foxconn. Though Taiwanese officials and analysts interpreted the probes as a sign that China wants Foxconn founder Terry Gou to drop plans to run in Taiwan’s presidential election in January, some have said Beijing may also be trying to pressure Foxconn into resisting decoupling with China.

“Any attempt to ‘talk down’ the mainland’s economy or to seek ‘decoupling’ is driven by ulterior motives and will be futile,” said a spokeswoman for Beijing’s Taiwan Affairs Office in September. “The mainland is always the best choice for Taiwanese compatriots and businesses.”

Fully decoupling from mainland China’s economy likely isn’t possible, and would be disastrous for Taiwan, not to mention China, even if it were.

Foxconn and other major Taiwanese companies depend heavily on China for parts, testing and buyers. Some 25% of Taiwan’s electronic-parts imports still come from the mainland.

If China’s weakened economy returns to strong growth, it could shift the calculus back in favor of the mainland, where the Communist Party claims Taiwan despite never having ruled it. About 21% of Taiwan’s total goods trade this year has been with mainland China, versus 14% for the U.S., though the U.S. share has risen from 11% in 2018.

“My hunch is that the large manufacturing sectors will try to stay in the Chinese market, even with harsh conditions,” said Alexander Huang, director of the international affairs department of the opposition Kuomintang Party, whose supporters include business people with mainland ties. “If you talk to those business owners, they say, ‘Nah, no way will I give it to my competitors.’”

Even so, many forces are pushing Taiwan to rewire its economic relationship with China.

Trump-era tariffs and Biden administration export controls have raised the cost of sourcing from China, and in some cases prohibited it. U.S. firms are pushing their Taiwanese suppliers to diversify sourcing, and rising wages in China have made it less attractive than before.

Long-running shifts in Taiwanese sentiment toward China—and China’s own efforts to punish the island using its economic leverage—are also factors. China has banned Taiwanese agricultural products such as pineapple and, in 2022, grouper fish, and restricted outbound tourism to Taiwan.

Those restrictions to some degree have backfired, pushing Taiwanese businesses to look elsewhere.

Casting for new markets

Chang Chia-sheng, who runs a fish farming operation in Taiwan, said his main export target a decade ago was mainland China. But as geopolitical tensions climbed, he looked elsewhere. Sales to Americans have jumped fivefold since 2018, he said. “In the U.S., things just seem to work out more easily,” Chang said.

The U.S. and Taiwan reached an agreement in May on a number of trade and investment measures to deepen ties, though the deal stopped short of reducing tariffs.

In the June quarter of 2023, 63% of revenue at TSMC, which makes most of the world’s most cutting-edge logic chips, came from the U.S., up from 54% in the same period in 2018, according to S&P Global data. Just 12% of TSMC’s revenue now comes from Chinese buyers, down from 22% in the second quarter of 2018.

Taiwan’s government is also encouraging closer economic links with Southeast Asia, South Asia, Australia and New Zealand. Its “New Southbound Policy,” rolled out in 2016, has been the subject of fierce debate in Taiwan, with the Kuomintang Party saying steps to boost relations—like handing out scholarships—aren’t worth the cost.

Exports to “New Southbound” partners have risen, however, to $66 billion in the first nine months of 2023, about 50% higher than the same period in 2016.

“Frankly speaking, we’re responding reactively” to the need for more diverse trading partners, Taiwan’s Economic Minister Wang Mei-hua said. “Taiwan needs to manage the risks on its own, but we also need our allies to join us more in mitigating these risks.”

Together, the U.S. and the six largest Southeast Asian economies accounted for 36% of Taiwanese exports in the third quarter of 2023, according to data from CEIC, surpassing the percentage sent to mainland China and Hong Kong on a quarterly basis for the first time since 2002.

In September, Taiwan sent less than 21% of its exports to the mainland, the lowest percentage since the global financial crisis.

Taiwanese foreign investment into mainland China, steady at around $10 billion a year for most of the early 2010s, plummeted in late 2018 and has since been running at about half that level, according to Taiwanese government data. In 2023 so far, just 13% of Taiwan’s investment went to mainland China; 25% went to other Asian locations, and nearly half went to the U.S.

A survey of Taiwanese businesses conducted last year on behalf of the Center for Strategic and International Studies, a Washington think tank, found that nearly 60% had moved or were considering moving some production or sourcing out of China—a significantly higher rate than European or American firms.

Jay Yen, chief executive of Yen and Brothers, a Taiwanese frozen-food processing company, said his firm received a government subsidy of around $75,000 to market his products to American consumers. China now only accounts for about 3% of its revenue, he said.

That said, “if you really have to consider the risks of a war between the U.S. and China and its potential impact on Taiwan, you might want to place your bets on a third country—neither China nor the U.S.,” Yen added.

Reversing the tide

After China began to open up its economy in the late 1970s, Taiwanese businesses were among the first investors.

By the 2000s, China seemed to be succeeding in its strategy of integrating the two economies, with more than 28% of Taiwan’s exports going to the mainland in 2010, from less than 4% a decade earlier.

Direct flights between the two sides were normalised for the first time in decades. Mainland tourists were allowed to visit Taiwan on their own.

By 2014, the tide was turning as more Taiwanese grew worried about over dependence on China. Student demonstrators protested against a trade pact, later abandoned, that would have deepened ties with China. President Tsai Ing-wen, who took office in 2016, has pushed to diversify Taiwan’s economy.

China has responded by moving trade issues more into the spotlight.

In April, it opened an investigation into Taiwanese trade restrictions that it says limit exports of more than 2,400 items from the mainland to the island in violation of World Trade Organization rules. In October, China’s Ministry of Commerce announced the probe would be extended until Jan. 12—the day before Taiwan’s coming election.

Taiwan’s government has called the probe politically motivated.

Chinese officials have implied that Beijing could suspend preferential tariff rates for some Taiwanese goods in China under a 2010 deal signed when Kuomintang’s Ma Ying-jeou was president. Beijing has also reacted angrily to Taiwan’s recent trade agreement with the U.S.

For Taiwanese companies, building and operating new factories in places other than China isn’t cheap or easy. Protests have at times disrupted operations at Indian plants operated by Foxconn and Wistron, another Apple supplier. In September, a fire halted production at a Taiwanese facility in Tamil Nadu.

Still, some Taiwanese businesspeople have clearly soured on China.

“The electronics industry has already become a Chinese empire, not a Taiwanese one,” says Leo Chiu, who worked in mainland China in quality control for an electronics manufacturer for 14 years before concluding he couldn’t move up further there and returning to Taiwan in 2019. Many of his old colleagues have left, he said.

“If Xi Jinping steps down, there’s still a chance it could change,” says Chiu. “But I think it’s very hard.”

Copyright 2020, Dow Jones & Company, Inc. All Rights Reserved Worldwide. LEARN MORE

Copyright 2020, Dow Jones & Company, Inc. All Rights Reserved Worldwide. LEARN MORE

This stylish family home combines a classic palette and finishes with a flexible floorplan

Just 55 minutes from Sydney, make this your creative getaway located in the majestic Hawkesbury region.

Continued stagflation and cost of living pressures are causing couples to think twice about starting a family, new data has revealed, with long term impacts expected

Australia is in the midst of a ‘baby recession’ with preliminary estimates showing the number of births in 2023 fell by more than four percent to the lowest level since 2006, according to KPMG. The consultancy firm says this reflects the impact of cost-of-living pressures on the feasibility of younger Australians starting a family.

KPMG estimates that 289,100 babies were born in 2023. This compares to 300,684 babies in 2022 and 309,996 in 2021, according to the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS). KPMG urban economist Terry Rawnsley said weak economic growth often leads to a reduced number of births. In 2023, ABS data shows gross domestic product (GDP) fell to 1.5 percent. Despite the population growing by 2.5 percent in 2023, GDP on a per capita basis went into negative territory, down one percent over the 12 months.

“Birth rates provide insight into long-term population growth as well as the current confidence of Australian families,” said Mr Rawnsley. “We haven’t seen such a sharp drop in births in Australia since the period of economic stagflation in the 1970s, which coincided with the initial widespread adoption of the contraceptive pill.”

Mr Rawnsley said many Australian couples delayed starting a family while the pandemic played out in 2020. The number of births fell from 305,832 in 2019 to 294,369 in 2020. Then in 2021, strong employment and vast amounts of stimulus money, along with high household savings due to lockdowns, gave couples better financial means to have a baby. This led to a rebound in births.

However, the re-opening of the global economy in 2022 led to soaring inflation. By the start of 2023, the Australian consumer price index (CPI) had risen to its highest level since 1990 at 7.8 percent per annum. By that stage, the Reserve Bank had already commenced an aggressive rate-hiking strategy to fight inflation and had raised the cash rate every month between May and December 2022.

Five more rate hikes during 2023 put further pressure on couples with mortgages and put the brakes on family formation. “This combination of the pandemic and rapid economic changes explains the spike and subsequent sharp decline in birth rates we have observed over the past four years,” Mr Rawnsley said.

The impact of high costs of living on couples’ decision to have a baby is highlighted in births data for the capital cities. KPMG estimates there were 60,860 births in Sydney in 2023, down 8.6 percent from 2019. There were 56,270 births in Melbourne, down 7.3 percent. In Perth, there were 25,020 births, down 6 percent, while in Brisbane there were 30,250 births, down 4.3 percent. Canberra was the only capital city where there was no fall in the number of births in 2023 compared to 2019.

“CPI growth in Canberra has been slightly subdued compared to that in other major cities, and the economic outlook has remained strong,” Mr Rawnsley said. “This means families have not been hurting as much as those in other capital cities, and in turn, we’ve seen a stabilisation of births in the ACT.”

This stylish family home combines a classic palette and finishes with a flexible floorplan

Just 55 minutes from Sydney, make this your creative getaway located in the majestic Hawkesbury region.