Elon Musk’s Lessons From Hell: Five Commandments for Business

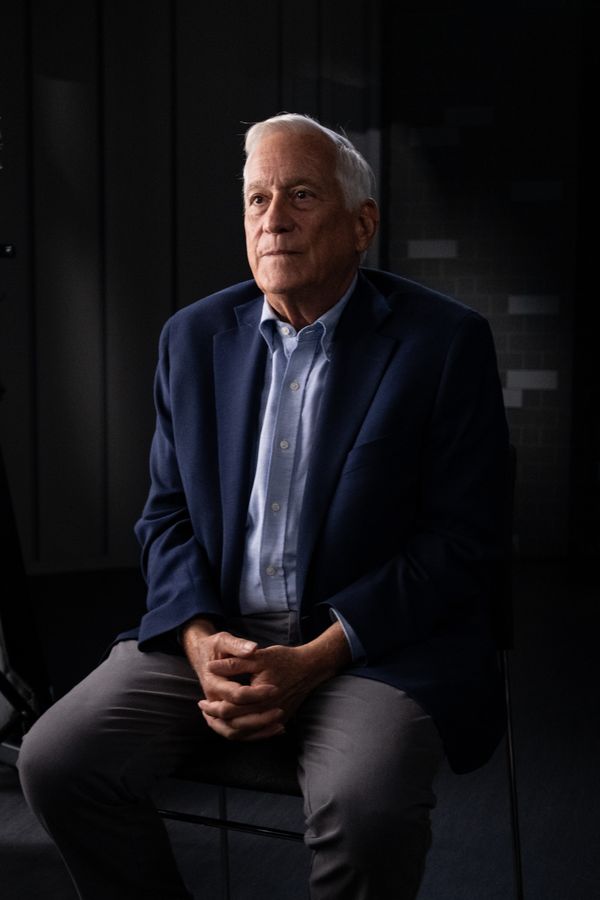

New book by biographer Walter Isaacson explores the billionaire’s leadership style and ‘demon mode’

Simply put: Elon Musk can be a real jerk.

And that has probably helped and hurt him in business, according to a new biography by Walter Isaacson.

In “Elon Musk,” out Tuesday, Isaacson puts forth the idea of “demon mode” to explain the temperamental impulses behind some of the tycoon’s successes—and setbacks. But it isn’t just demon mode that has fuelled his rise. Isaacson details other teachable ways the billionaire’s methods have helped make him the world’s richest man.

Both sides of Musk are sure to become part of B-school lore for a new generation of would-be entrepreneurs and business managers picking and choosing which traits and tactics to emulate.

Isaacson had previously made the concept of the “reality distortion field” popular with his bestselling 2011 book about Apple co-founder Steve Jobs and his ability to bend perception to motivate others.

Demon mode was on display in 2018 as Musk struggled to ramp up production of Tesla’s Model 3 sedan, which nearly destroyed the electric-car company and which the CEO dubbed production hell.

That experience through hell, the book says, also helped Musk shape five commandments for how he wants problems solved by his workers across his companies, from rocket maker SpaceX to social-media platform X, formerly Twitter.

Musk, in the book, calls the framework for problem solving “the algorithm.” In short, Musk urges his employees to:

- Question every requirement

- Delete any part or process you can

- Simplify and optimise

- Accelerate cycle time

- Automate

“His executives sometimes move their lips and mouth the words, like they would chant the liturgy along with their priest,” Isaacson wrote of Musk’s mantra.

In the book, Musk acknowledges he talks about the approach often. “I became a broken record on the algorithm,” Musk is quoted as saying. “But I think it’s helpful to say it to an annoying degree.”

The approach builds off a long-held method for problem solving touted by Musk called first principles, a reasoning that breaks tasks into their very basics without simply reverting to what has been done before.

“The algorithm is a five-step process for not only making good products and designing good products, but manufacturing them,” Isaacson said in an interview Monday.

“It begins with first principles. He says, question every requirement, and, by first principles he means, look down at the physics. If somebody says, no, we can’t build it at this price, he says, tell me how much the materials cost. Tell me exactly what’s involved here and then tell me you can or can’t do it.”

There are other lessons in the book that Musk has long practiced, such as never asking an employee to do something you aren’t willing to do (hence his sleeping on factory floors), hiring employees based on their attitude, and saying “it’s OK to be wrong. Just don’t be confident and wrong.”

Telling Musk bad news, however, has been seen by some employees as dangerous to one’s career.

“One of his problems is people sometimes are afraid to tell him the bad news,” Isaacson said. “Those who succeed around Musk are those who figure out you got to give him the bad news even if it’s going to result in some unpleasant scenes.”

Their fear is often rooted in demon mode.

Claire Boucher, known as the musician Grimes and the mother of three of Musk’s children, coined the term in an interview with Isaacson.

“Demon mode is when he goes dark and retreats inside the storm in his brain,” Boucher said in the book. “Demon mode,” she added, “causes a lot of chaos but it also gets s— done.”

And Musk has gotten a lot done, helping usher in the electric-car era as Tesla chief executive and igniting the commercial space race with SpaceX, which he founded. His messy stewardship of X, however, is testing public perception of his business genius.

Isaacson, who shadowed Musk for two years in reporting the book, saw demon mode in person several times along with other personalities that he described as ranging from silly to charming. He suggests the roots of the dark clouds come from the 52-year-old’s childhood in South Africa.

“It’s almost like Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde where a cloud comes over and he gets into a trance and he can just be tough in a cold way,” Isaacson said. “He never gets really angry, never gets that physical, but coldly brutal to people and he almost doesn’t remember afterwards what he’s done. Sometimes I’ll say, why did you say that to that person? And he’ll look at me blankly as if he didn’t quite remember what happened while he was in demon mode.”

In one instance, Isaacson described seeing demon mode emerge when Musk saw SpaceX’s launchpad in South Texas empty late one evening.

“He orders a hundred people to come in from different parts of SpaceX from Florida, California so they can all work for 24 hours a day getting this thing done even though there was no need to,” Isaacson said.

Such surges seem to play in tandem to Musk’s need for drama.

“He is a drama magnet,” Musk’s younger brother, Kimbal, said in the book. “That’s his compulsion, the theme of his life.”

Isaacson cautions that readers shouldn’t come away thinking they can be just like Musk and automatically succeed. Rather, he said, readers should see both how leaders such as Musk and the late Jobs were effective and also take away cautionary tales.

“You don’t have to be this mean,” he said.

Still, throughout his book, Isaacson chases the question of whether Musk could be successful any other way.

“I try to show how that’s one of the strands in a fabric and as Shakespeare said, we’re moulded out of our faults,” Isaacson said. “If we pull that strand out, you might not get the whole cloth of Elon Musk.”

Copyright 2020, Dow Jones & Company, Inc. All Rights Reserved Worldwide. LEARN MORE

Copyright 2020, Dow Jones & Company, Inc. All Rights Reserved Worldwide. LEARN MORE

This stylish family home combines a classic palette and finishes with a flexible floorplan

Just 55 minutes from Sydney, make this your creative getaway located in the majestic Hawkesbury region.

Continued stagflation and cost of living pressures are causing couples to think twice about starting a family, new data has revealed, with long term impacts expected

Australia is in the midst of a ‘baby recession’ with preliminary estimates showing the number of births in 2023 fell by more than four percent to the lowest level since 2006, according to KPMG. The consultancy firm says this reflects the impact of cost-of-living pressures on the feasibility of younger Australians starting a family.

KPMG estimates that 289,100 babies were born in 2023. This compares to 300,684 babies in 2022 and 309,996 in 2021, according to the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS). KPMG urban economist Terry Rawnsley said weak economic growth often leads to a reduced number of births. In 2023, ABS data shows gross domestic product (GDP) fell to 1.5 percent. Despite the population growing by 2.5 percent in 2023, GDP on a per capita basis went into negative territory, down one percent over the 12 months.

“Birth rates provide insight into long-term population growth as well as the current confidence of Australian families,” said Mr Rawnsley. “We haven’t seen such a sharp drop in births in Australia since the period of economic stagflation in the 1970s, which coincided with the initial widespread adoption of the contraceptive pill.”

Mr Rawnsley said many Australian couples delayed starting a family while the pandemic played out in 2020. The number of births fell from 305,832 in 2019 to 294,369 in 2020. Then in 2021, strong employment and vast amounts of stimulus money, along with high household savings due to lockdowns, gave couples better financial means to have a baby. This led to a rebound in births.

However, the re-opening of the global economy in 2022 led to soaring inflation. By the start of 2023, the Australian consumer price index (CPI) had risen to its highest level since 1990 at 7.8 percent per annum. By that stage, the Reserve Bank had already commenced an aggressive rate-hiking strategy to fight inflation and had raised the cash rate every month between May and December 2022.

Five more rate hikes during 2023 put further pressure on couples with mortgages and put the brakes on family formation. “This combination of the pandemic and rapid economic changes explains the spike and subsequent sharp decline in birth rates we have observed over the past four years,” Mr Rawnsley said.

The impact of high costs of living on couples’ decision to have a baby is highlighted in births data for the capital cities. KPMG estimates there were 60,860 births in Sydney in 2023, down 8.6 percent from 2019. There were 56,270 births in Melbourne, down 7.3 percent. In Perth, there were 25,020 births, down 6 percent, while in Brisbane there were 30,250 births, down 4.3 percent. Canberra was the only capital city where there was no fall in the number of births in 2023 compared to 2019.

“CPI growth in Canberra has been slightly subdued compared to that in other major cities, and the economic outlook has remained strong,” Mr Rawnsley said. “This means families have not been hurting as much as those in other capital cities, and in turn, we’ve seen a stabilisation of births in the ACT.”

This stylish family home combines a classic palette and finishes with a flexible floorplan

Just 55 minutes from Sydney, make this your creative getaway located in the majestic Hawkesbury region.