Fed Approves Quarter-Point Rate Hike, Signals More Increases Likely

Officials are slowing interest-rate increases as they debate when to pause

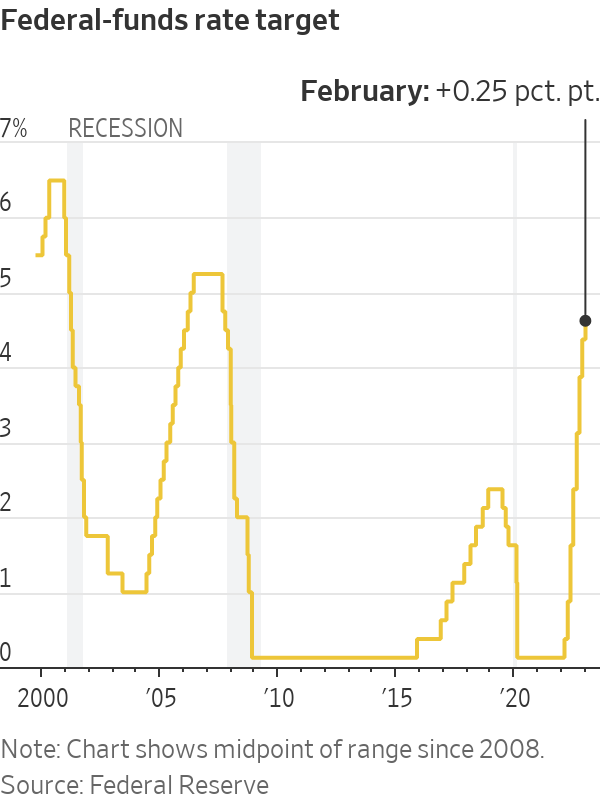

WASHINGTON—The Federal Reserve approved an interest-rate increase of a quarter-percentage-point and signalled plans to raise rates again next month to continue lowering inflation.

The decision Wednesday followed six consecutive rate rises that were larger, including an increase of a half-point in December and a 0.75-point increase in November.

Officials nodded to recent improvement in inflation readings but didn’t significantly alter their guidance in a policy statement released after the meeting regarding coming rate moves.

“The committee anticipates that ongoing increases” in interest rates “will be appropriate in order to attain a stance of monetary policy that is sufficiently restrictive,” said the statement, using the same language included in policy statements since last March.

The latest increase caps a year in which the Fed lifted its benchmark federal-funds rate from near zero to a range between 4.5% and 4.75%, a level last reached in 2007. That extends the central bank’s most rapid pace of rate increases since the early 1980s to fight inflation, which hit a 40-year high last year.

One big question heading into Wednesday’s meeting was the extent to which recent economic data had given Fed officials more confidence that inflation and wage pressures had peaked.

In December, most of them penciled in raising the fed-funds rate to a range between 5% and 5.25% this year. After the hike they approved Wednesday, that projection would imply additional quarter-point increases at the Fed’s meetings in March and May, followed by a pause in rate rises.

Many officials had repeated in recent weeks that they still saw such a rate path as appropriate given strong wage pressures, a tight labour market and high service-sector inflation. But officials also said they would base their decisions on how the economy performs in the coming months.

“We can now say for the first time, the disinflationary process has started,” said Fed Chair Jerome Powell at a news conference after Wednesday’s meeting. But he added, “The job is not fully done.”

Mr. Powell said the central bank was trying to manage the risk of raising rates too much and causing unnecessary economic harm with that of not doing enough to bring down inflation. In repeating his longstanding view that the latter mistake would be harder to fix, Mr. Powell said he didn’t want to be in a position where six or 12 months from now, after a halt to raising rates, the Fed would belatedly conclude that it hadn’t done enough to bring down inflation this year and would have to raise rates higher.

“We’re going to be cautious about declaring victory and sending signals that we think the game is won,” he said. “Certainty is just not appropriate here.”

The fed-funds rate influences other borrowing costs throughout the economy, including rates on mortgages, credit cards and auto loans. The Fed is raising rates to cool inflation by slowing economic growth. It believes those policy moves work through financial markets by tightening financial conditions, such as by raising borrowing costs or lowering prices of stocks and other assets.

Officials have been guarded in recent weeks about providing any guidance that might ignite market rallies that could undermine their efforts to fight inflation.

In recent weeks, markets have rallied partly because investors anticipated that the Fed would slow its rate increases this week and remove uncertainty over the rate outlook, which reduces interest-rate volatility. Lower volatility can ease financial conditions.

Markets have also been cheered by news that inflation and wage growth might have peaked last year, which could make the Fed more comfortable in pausing rate increases. Since Fed officials met in December, economic activity has been mixed. Consumer spending has moderated, and manufacturing activity has weakened. But hiring has held steady, pushing the unemployment down to 3.5% in December, a half-century low.

Investors in bond markets increasingly expect that the Fed will cut interest rates later this year because of a sharp slowdown in economic activity that lowers inflation faster than policy makers expect.

Fed officials and some economists, meanwhile, are concerned that the recent decline in inflation could reflect the long-anticipated easing of supply-chain bottlenecks—and that might not be enough to bring inflation down to the Fed’s 2% goal.

“I’m somewhat worried that the market view is based more on hope,” said Karen Dynan, an economist at Harvard University who served in the Obama administration. “Labor markets still look really tight.”

Officials’ deliberations over how much more to raise rates this year and how long to hold rates at some higher level could hinge over how much they think their past increases will slow the economy this year. Debates could also turn on the degree to which wage and price pressures might slow without significant weakness in the job market.

Officials agreed to slow rate rises to gain more time to study the effects of their moves.

Inflation fell to 4.4% in December from 5.2% in September, as measured by the 12-month change in the personal consumption expenditures price index excluding food and energy. Though still above the Fed’s 2% goal, it moderated in the October-to-December period to an annualised 2.9% rate.

“Inflation has eased somewhat but remains elevated,” said the Fed’s policy statement.

Overall inflation is slowing largely because prices of energy and other goods are falling. Large increases in housing costs have slowed, but haven’t filtered through to official price gauges yet. As a result, Mr. Powell and several colleagues shifted attention recently toward a narrower subset of labor-intensive services by excluding prices for food, energy, shelter and goods.

Mr. Powell has said prices in this category, which rose 4% in December from a year earlier, offer the best gauge of higher wage costs passing through to consumer prices.

Copyright 2020, Dow Jones & Company, Inc. All Rights Reserved Worldwide. LEARN MORE

Copyright 2020, Dow Jones & Company, Inc. All Rights Reserved Worldwide. LEARN MORE

This stylish family home combines a classic palette and finishes with a flexible floorplan

Just 55 minutes from Sydney, make this your creative getaway located in the majestic Hawkesbury region.

Continued stagflation and cost of living pressures are causing couples to think twice about starting a family, new data has revealed, with long term impacts expected

Australia is in the midst of a ‘baby recession’ with preliminary estimates showing the number of births in 2023 fell by more than four percent to the lowest level since 2006, according to KPMG. The consultancy firm says this reflects the impact of cost-of-living pressures on the feasibility of younger Australians starting a family.

KPMG estimates that 289,100 babies were born in 2023. This compares to 300,684 babies in 2022 and 309,996 in 2021, according to the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS). KPMG urban economist Terry Rawnsley said weak economic growth often leads to a reduced number of births. In 2023, ABS data shows gross domestic product (GDP) fell to 1.5 percent. Despite the population growing by 2.5 percent in 2023, GDP on a per capita basis went into negative territory, down one percent over the 12 months.

“Birth rates provide insight into long-term population growth as well as the current confidence of Australian families,” said Mr Rawnsley. “We haven’t seen such a sharp drop in births in Australia since the period of economic stagflation in the 1970s, which coincided with the initial widespread adoption of the contraceptive pill.”

Mr Rawnsley said many Australian couples delayed starting a family while the pandemic played out in 2020. The number of births fell from 305,832 in 2019 to 294,369 in 2020. Then in 2021, strong employment and vast amounts of stimulus money, along with high household savings due to lockdowns, gave couples better financial means to have a baby. This led to a rebound in births.

However, the re-opening of the global economy in 2022 led to soaring inflation. By the start of 2023, the Australian consumer price index (CPI) had risen to its highest level since 1990 at 7.8 percent per annum. By that stage, the Reserve Bank had already commenced an aggressive rate-hiking strategy to fight inflation and had raised the cash rate every month between May and December 2022.

Five more rate hikes during 2023 put further pressure on couples with mortgages and put the brakes on family formation. “This combination of the pandemic and rapid economic changes explains the spike and subsequent sharp decline in birth rates we have observed over the past four years,” Mr Rawnsley said.

The impact of high costs of living on couples’ decision to have a baby is highlighted in births data for the capital cities. KPMG estimates there were 60,860 births in Sydney in 2023, down 8.6 percent from 2019. There were 56,270 births in Melbourne, down 7.3 percent. In Perth, there were 25,020 births, down 6 percent, while in Brisbane there were 30,250 births, down 4.3 percent. Canberra was the only capital city where there was no fall in the number of births in 2023 compared to 2019.

“CPI growth in Canberra has been slightly subdued compared to that in other major cities, and the economic outlook has remained strong,” Mr Rawnsley said. “This means families have not been hurting as much as those in other capital cities, and in turn, we’ve seen a stabilisation of births in the ACT.”

This stylish family home combines a classic palette and finishes with a flexible floorplan

Just 55 minutes from Sydney, make this your creative getaway located in the majestic Hawkesbury region.