How Margin Debt Works

Money that is borrowed to buy stocks is sometimes an indicator of future market performance. Here is how it works and why the matter is relevant now.

Margin debt is a sometimes-overlooked but key part of the stock market that is particularly pertinent right now.

It is the money that investors borrow from stockbrokers to buy securities when they can’t or don’t want to fund the entire purchase with cash. Say an investor wants to purchase 100 shares at $50 each for a total of $5,000 but has only $2,500 to invest. That individual could buy the rest of the shares on margin. The same process can be used to buy exchange-traded funds.

Investors frequently use margin to get more bang for their investing buck. “The pro of margin is that it increases your purchasing power,” says Jeff Deiss, director of wealth planning at ACM in Ridgewood, N.J.

The downside is that brokers typically charge interest on borrowed money. And if the individual starts losing money on the investment, the stockbroker might ask for additional cash as security or collateral. That decision and how much cash will be required will depend on a variety of factors, including the remaining value of the investment, how much money the investor owes the broker and the requirements of the broker.

“Buying on margin comes with a lot of risk, and if you are going to use margin, it is probably a good idea to have some cash on the side,” says Mr. Deiss. Investors who don’t have the required additional cash may be forced to close out their positions at a loss.

A large amount of buying on margin also can be detrimental to the stock market as a whole.

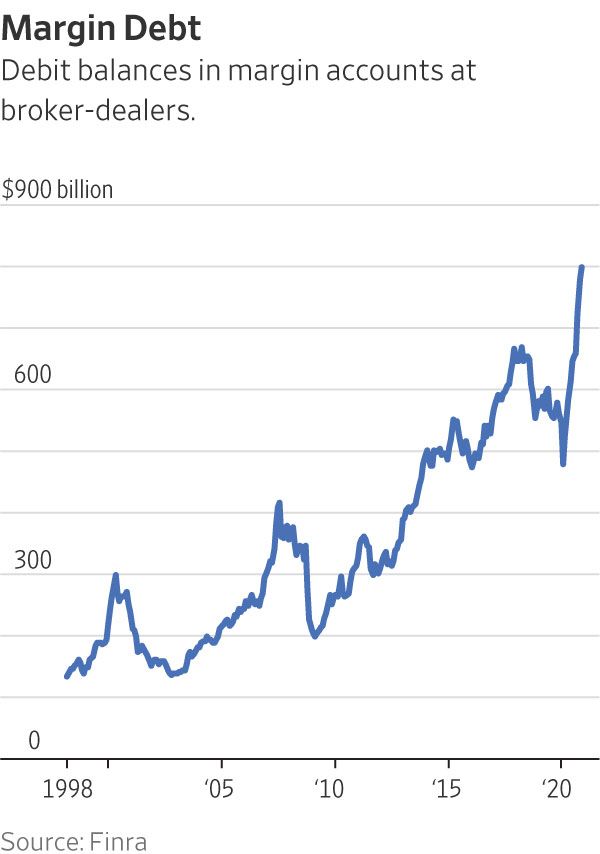

At the end of January, customer margin debt at U.S. brokers regulated by the Financial Industry Regulatory Authority, or Finra, jumped to $799 billion from $562 billion a year earlier, according to data provided by Finra.

Some analysts say that jump in margin debt came from individual investors, who turned to online trading amid pandemic-related lockdowns. A combination of new easy-to-use trading technology, ultralow borrowing costs and stimulus checks from the federal government helped fuel the phenomenon.

“For younger folks, it’s kind of the drug of choice,” Mr. Deiss says.

The problem is, when there is a lot of margin debt concentrated in a few stocks, those stocks tend to see wild price swings, says Fabiana Fedeli, global head of fundamental equities at Rotterdam-based asset-management company Robeco. Anecdotal evidence indicates that the recent increase in margin debt coincided with higher participation levels by individual investors, she says.

Indeed, certain stocks that became popular with individual investors also saw price volatility earlier this year. “The minute that the margin couldn’t be met, some of the positions had to be sold immediately,” Ms. Fedeli says. “It gives volatility to the market,” she says.

Copyright 2020, Dow Jones & Company, Inc. All Rights Reserved Worldwide. LEARN MORE

Copyright 2020, Dow Jones & Company, Inc. All Rights Reserved Worldwide. LEARN MORE

This stylish family home combines a classic palette and finishes with a flexible floorplan

Just 55 minutes from Sydney, make this your creative getaway located in the majestic Hawkesbury region.

Continued stagflation and cost of living pressures are causing couples to think twice about starting a family, new data has revealed, with long term impacts expected

Australia is in the midst of a ‘baby recession’ with preliminary estimates showing the number of births in 2023 fell by more than four percent to the lowest level since 2006, according to KPMG. The consultancy firm says this reflects the impact of cost-of-living pressures on the feasibility of younger Australians starting a family.

KPMG estimates that 289,100 babies were born in 2023. This compares to 300,684 babies in 2022 and 309,996 in 2021, according to the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS). KPMG urban economist Terry Rawnsley said weak economic growth often leads to a reduced number of births. In 2023, ABS data shows gross domestic product (GDP) fell to 1.5 percent. Despite the population growing by 2.5 percent in 2023, GDP on a per capita basis went into negative territory, down one percent over the 12 months.

“Birth rates provide insight into long-term population growth as well as the current confidence of Australian families,” said Mr Rawnsley. “We haven’t seen such a sharp drop in births in Australia since the period of economic stagflation in the 1970s, which coincided with the initial widespread adoption of the contraceptive pill.”

Mr Rawnsley said many Australian couples delayed starting a family while the pandemic played out in 2020. The number of births fell from 305,832 in 2019 to 294,369 in 2020. Then in 2021, strong employment and vast amounts of stimulus money, along with high household savings due to lockdowns, gave couples better financial means to have a baby. This led to a rebound in births.

However, the re-opening of the global economy in 2022 led to soaring inflation. By the start of 2023, the Australian consumer price index (CPI) had risen to its highest level since 1990 at 7.8 percent per annum. By that stage, the Reserve Bank had already commenced an aggressive rate-hiking strategy to fight inflation and had raised the cash rate every month between May and December 2022.

Five more rate hikes during 2023 put further pressure on couples with mortgages and put the brakes on family formation. “This combination of the pandemic and rapid economic changes explains the spike and subsequent sharp decline in birth rates we have observed over the past four years,” Mr Rawnsley said.

The impact of high costs of living on couples’ decision to have a baby is highlighted in births data for the capital cities. KPMG estimates there were 60,860 births in Sydney in 2023, down 8.6 percent from 2019. There were 56,270 births in Melbourne, down 7.3 percent. In Perth, there were 25,020 births, down 6 percent, while in Brisbane there were 30,250 births, down 4.3 percent. Canberra was the only capital city where there was no fall in the number of births in 2023 compared to 2019.

“CPI growth in Canberra has been slightly subdued compared to that in other major cities, and the economic outlook has remained strong,” Mr Rawnsley said. “This means families have not been hurting as much as those in other capital cities, and in turn, we’ve seen a stabilisation of births in the ACT.”

This stylish family home combines a classic palette and finishes with a flexible floorplan

Just 55 minutes from Sydney, make this your creative getaway located in the majestic Hawkesbury region.