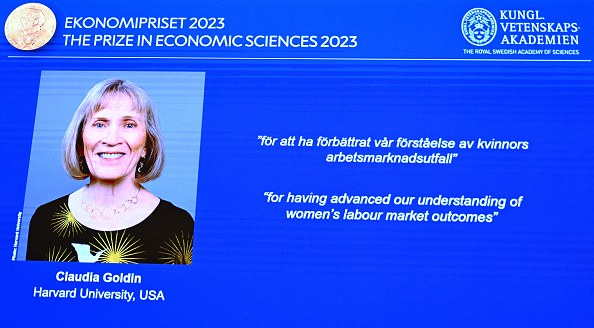

Nobel Prize in Economics Awarded to Harvard’s Claudia Goldin for Work on Gender Gaps

Economic historian and labour economist has tracked the changing fortunes of women in the workplace

BOSTON—Harvard University’s Claudia Goldin is a labor economist, teacher and mentor. She is now also a Nobel Prize winner for her groundbreaking research on women in the workforce.

Goldin was awarded the Nobel Prize in Economic Sciences on Monday, the third woman to receive the economics prize since the award started in 1969. The 77-year-old Harvard economist has spent decades analysing troves of data to produce research illuminating the history of women’s job-market experiences.

Goldin’s expansive work portfolio includes pieces on the drivers of female labor-force participation, the origins of the gender pay gap and hiring biases against women. Her paper, “Why Women Won,” which documented the evolution of women’s legal rights, published this month.

“Goldin’s discoveries have vast societal implications,” said Randi Hjalmarsson, professor of economics at the University of Gothenburg in Sweden.

Goldin was admittedly tired upon entering Monday’s press conference at Harvard. She was, after all, asleep when she received the early-morning call with the news of her Nobel Prize. Still, her passion regarding decades of research and relationship-building radiated as she spoke at a press briefing.

“The increase of women in economics is important for a host of reasons,” Goldin said. “For me personally it has been important because I have had the most wonderful co-authors.”

One such co-researcher, Claudia Olivetti of Dartmouth College, said Goldin’s body of work has shaped much of the current research on women and labor markets. Perhaps less well known, Olivetti said, is Goldin’s extraordinary mentorship of women.

Goldin “has been a source of inspiration to many women in economics, generously sharing her experiences and demonstrating the possibilities of success,” Olivetti said.

Some professors view themselves as researchers, rather than teachers. Not Goldin.

“I could never do research without doing teaching,” she said. “When I teach, I am forced to confront what I think is the truth.”

Goldin was the first woman to secure tenure in Harvard’s economics department. She follows Esther Duflo in 2019 and Elinor Ostrom in 2009 as female recipients of the economics Nobel Prize.

Goldin is married to Lawrence Katz, also a Harvard economist. Both are avid bird watchers and hikers, colleagues said. She has a 13-year-old golden retriever named Pika and no children.

Around the world, 50% of women have paid jobs, compared with 80% of men, although that gap is smaller in advanced economies. Across the developed economies, women earn 13% less on average and are less likely to play senior roles in the organisations they work for.

Goldin’s research questioned the assumption that women had steadily, or would inevitably, narrow those gaps. Using data that had previously attracted little attention, she established that far fewer women worked in paid employment in the early 1900s than in 1800, while that share rebounded as the 20th century advanced, albeit slowly.

Her writing includes 1990’s “Understanding the Gender Gap: An Economic History of American Women.” Examining 200 years of data, Goldin tracked the changing fortunes of women in the workplace as it changed from farm to factory to office.

She also identified some of the considerations that affected the decisions made by women about their participation in the workforce, as well as the constraints they faced at particular times. In one well-known paper, she examined the effect of the contraceptive pill on decisions about work and marriage.

The pay gap between male and female workers had long been attributed to differences in educational attainment, with women typically spending fewer years in formal education.

But that can no longer be true of many developed countries, where women are now better educated on average than men. Instead, Goldin’s work indicates that the gap in pay occurs with the birth of a first child, with women typically devoting more time to child care.

But darker forces are also at work. In one paper, Goldin and co-author Cecilia Rouse from Princeton University showed that the number of female members of the leading U.S. symphony orchestras rose sharply in the 1980s partly because of the adoption of “blind” auditions, where the candidate for an orchestra position auditioned behind a screen, concealing their gender or race from those doing the hiring.

In their paper, called “Orchestrating Impartiality: The Impact of ‘Blind Auditions’ on Female Musicians,” the authors found data across decades of hiring by symphonies both before and after the introduction of blind auditions to show that about a quarter of the increase in female members of orchestras over that time was due to blind auditions, suggesting previous bias.

Copyright 2020, Dow Jones & Company, Inc. All Rights Reserved Worldwide. LEARN MORE

Copyright 2020, Dow Jones & Company, Inc. All Rights Reserved Worldwide. LEARN MORE

This stylish family home combines a classic palette and finishes with a flexible floorplan

Just 55 minutes from Sydney, make this your creative getaway located in the majestic Hawkesbury region.

Continued stagflation and cost of living pressures are causing couples to think twice about starting a family, new data has revealed, with long term impacts expected

Australia is in the midst of a ‘baby recession’ with preliminary estimates showing the number of births in 2023 fell by more than four percent to the lowest level since 2006, according to KPMG. The consultancy firm says this reflects the impact of cost-of-living pressures on the feasibility of younger Australians starting a family.

KPMG estimates that 289,100 babies were born in 2023. This compares to 300,684 babies in 2022 and 309,996 in 2021, according to the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS). KPMG urban economist Terry Rawnsley said weak economic growth often leads to a reduced number of births. In 2023, ABS data shows gross domestic product (GDP) fell to 1.5 percent. Despite the population growing by 2.5 percent in 2023, GDP on a per capita basis went into negative territory, down one percent over the 12 months.

“Birth rates provide insight into long-term population growth as well as the current confidence of Australian families,” said Mr Rawnsley. “We haven’t seen such a sharp drop in births in Australia since the period of economic stagflation in the 1970s, which coincided with the initial widespread adoption of the contraceptive pill.”

Mr Rawnsley said many Australian couples delayed starting a family while the pandemic played out in 2020. The number of births fell from 305,832 in 2019 to 294,369 in 2020. Then in 2021, strong employment and vast amounts of stimulus money, along with high household savings due to lockdowns, gave couples better financial means to have a baby. This led to a rebound in births.

However, the re-opening of the global economy in 2022 led to soaring inflation. By the start of 2023, the Australian consumer price index (CPI) had risen to its highest level since 1990 at 7.8 percent per annum. By that stage, the Reserve Bank had already commenced an aggressive rate-hiking strategy to fight inflation and had raised the cash rate every month between May and December 2022.

Five more rate hikes during 2023 put further pressure on couples with mortgages and put the brakes on family formation. “This combination of the pandemic and rapid economic changes explains the spike and subsequent sharp decline in birth rates we have observed over the past four years,” Mr Rawnsley said.

The impact of high costs of living on couples’ decision to have a baby is highlighted in births data for the capital cities. KPMG estimates there were 60,860 births in Sydney in 2023, down 8.6 percent from 2019. There were 56,270 births in Melbourne, down 7.3 percent. In Perth, there were 25,020 births, down 6 percent, while in Brisbane there were 30,250 births, down 4.3 percent. Canberra was the only capital city where there was no fall in the number of births in 2023 compared to 2019.

“CPI growth in Canberra has been slightly subdued compared to that in other major cities, and the economic outlook has remained strong,” Mr Rawnsley said. “This means families have not been hurting as much as those in other capital cities, and in turn, we’ve seen a stabilisation of births in the ACT.”

This stylish family home combines a classic palette and finishes with a flexible floorplan

Just 55 minutes from Sydney, make this your creative getaway located in the majestic Hawkesbury region.