One-Percenters Keep Shopping at the Dollar Store

Wealthy consumers scour discount-chain aisles for bargains

That Mercedes in the dollar-store parking lot isn’t an illusion.

High-earners joined the rest of the country in flooding discount retailers such as Dollar General, Aldi grocery store and Five Below as prices for food and staples rose. Now, with inflation at half its peak, they aren’t letting up.

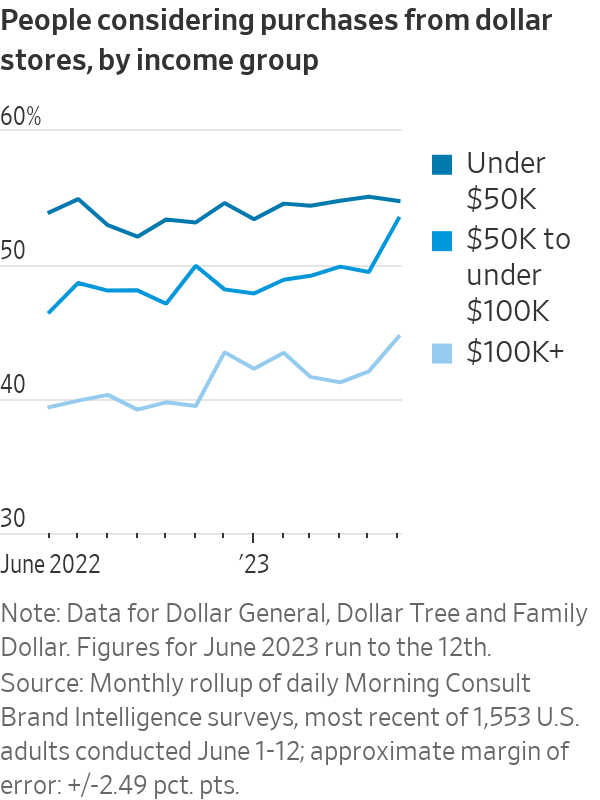

InMarket, which tracks retailer foot traffic, measured a 4% average increase in the share of dollar-store visits this year among those making more than $100,000, compared with the second half of 2022. Households with six-figure incomes are 15% more likely to say they would shop at dollar stores than they were last June, going from 39% to 45%, according to daily surveys from Morning Consult of about 50,000 Americans.

Wealthy Americans long viewed discount stores as “not for them,” says Michael Liersch, who consults with high-net-worth individuals as head of advice and planning at Wells Fargo. Yet paying $8 for a carton of eggs struck even many affluent people as ridiculous.

Overspending on things was once fashionable for some, Liersch says. “These days, it’s about making the most of your money and not getting ripped off.”

No matter how much you make, consumers say, there is no longer a stigma in going after a good deal.

Cheap kombucha

Autry Liggett, who works in operations for a Santa Barbara, Calif., hedge fund, exclusively shopped at Whole Foods and other high-end chains for groceries and household goods until recently. Growing up, he says he looked down on what he saw as poor-quality products at discount retailers.

Then, one of his friends brought over a case of 99-cent-store kombucha and probiotic drinks a few months ago. “She makes good money, so I just assumed she also shopped at Whole Foods and the other places I shop,” he says. “I was shocked.”

He now pops into the 99 Cents Only store downtown at least once a week, making sure to visit on Tuesday or Thursday, when they restock, for the best selection. He recently bought vitamins that retail at Whole Foods for $25 for $1.99, and a pint of organic blueberries for 99 cents.

A Dollar General spokeswoman says the brand has attracted and retained higher-income customers lately. A recently updated fresh-produce section, now available in nearly 3,900 stores, might be bringing more customers in.

Plenty of wealthy people point out that they got that way partly by not overspending on the small stuff—especially when it is all the same stuff.

“A carrot is a carrot is a carrot,” says Morgan Pierce, who earns about $200,000 a year working at McDonald’s Chicago corporate office. She frequently hits up Aldi and her local dollar store for groceries and other staples. Her last birthday party featured a private chef—and $1 plates and decorations.

Pierce, who was quick to tell her guests where many of the party supplies came from, says people were impressed. It is a shift from how she felt as a child, when she questioned why her family always had to hunt for sales. Now, she says she realises her mom has always been a bargain hound.

“Not everything on the shelves is well-made, but there are things that are, and I am not ashamed to go into those places and get them, and I’m not afraid to tell people about it,” Pierce says.

Bob Gillman, an executive transition consultant, has shopped at Aldi and other discount chains for decades. He didn’t mention the habit to his friends until recently, when a branch popped up near his tony Palm Springs, Calif., community.

“We see lots of people driving Porsches, Mercedes and BMWs in the parking lot,” Gillman says. “No matter how much you make, you don’t want to spend $4 on an avocado when you can get one for 59 cents.”

Few seem to mind feeding a quarter to check out a shopping cart, or bagging their own groceries, Gillman says.

Gillman’s daughter, Rachel Gillman Rischall, often rolled her eyes at her dad’s zealous discount shopping. That is, until this past year, when her grocery bills soared, and birthday-party gifts for her kids’ friends topped $50 a pop near her Chicago home. Fed up, she checked out the toy selection at Five Below and hasn’t looked back. She also now buys journals, art supplies, stationery and snacks there.

“My dad is so proud,” she says.

Shopping at dollar stores is a choice for some, yet it is a necessity for many, and Americans increasingly get their groceries from these retailers.

Expanding into more-prosperous areas is part of Aldi’s strategy, analysts say. The retailer plans to add 120 new U.S. stores in 2023, after opening and remodelling 139 stores last year. The brand says it attracted 9.4 million new U.S. customers in 2022.

Budget influence

Social media is also helping make dollar and discount stores cool. Videos tagged #dollartree have a combined 7.6 billion views on TikTok. Many feature influencers trying out what are known as dupes of popular high-end beauty products and other goods.

Entrepreneur Bethenny Frankel says her discount and drugstore hauls have attracted more attention than anything she did when she was featured on the reality show “The Real Housewives of New York City.”

“I go in there with my Hermès bag,” says Frankel, whose YouTube and TikTok videos shopping at dollar stores and unboxing ultra cheap products regularly ring up millions of views. She says she isn’t paid by any of the discount chains for her videos.

While some viewers have accused her of pretending to like and use a $1 lip gloss or storage bin when she could easily afford its more expensive counterpart, Frankel says her enthusiasm is genuine.

“What’s the difference between a dollar-store and a $20 pair of flip flops? Is there such a thing as truffle-oil-infused rubber?” she says. Lip gloss, meanwhile, “stays on for five minutes no matter how much you spend.”

Copyright 2020, Dow Jones & Company, Inc. All Rights Reserved Worldwide. LEARN MORE

Copyright 2020, Dow Jones & Company, Inc. All Rights Reserved Worldwide. LEARN MORE

This stylish family home combines a classic palette and finishes with a flexible floorplan

Just 55 minutes from Sydney, make this your creative getaway located in the majestic Hawkesbury region.

Continued stagflation and cost of living pressures are causing couples to think twice about starting a family, new data has revealed, with long term impacts expected

Australia is in the midst of a ‘baby recession’ with preliminary estimates showing the number of births in 2023 fell by more than four percent to the lowest level since 2006, according to KPMG. The consultancy firm says this reflects the impact of cost-of-living pressures on the feasibility of younger Australians starting a family.

KPMG estimates that 289,100 babies were born in 2023. This compares to 300,684 babies in 2022 and 309,996 in 2021, according to the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS). KPMG urban economist Terry Rawnsley said weak economic growth often leads to a reduced number of births. In 2023, ABS data shows gross domestic product (GDP) fell to 1.5 percent. Despite the population growing by 2.5 percent in 2023, GDP on a per capita basis went into negative territory, down one percent over the 12 months.

“Birth rates provide insight into long-term population growth as well as the current confidence of Australian families,” said Mr Rawnsley. “We haven’t seen such a sharp drop in births in Australia since the period of economic stagflation in the 1970s, which coincided with the initial widespread adoption of the contraceptive pill.”

Mr Rawnsley said many Australian couples delayed starting a family while the pandemic played out in 2020. The number of births fell from 305,832 in 2019 to 294,369 in 2020. Then in 2021, strong employment and vast amounts of stimulus money, along with high household savings due to lockdowns, gave couples better financial means to have a baby. This led to a rebound in births.

However, the re-opening of the global economy in 2022 led to soaring inflation. By the start of 2023, the Australian consumer price index (CPI) had risen to its highest level since 1990 at 7.8 percent per annum. By that stage, the Reserve Bank had already commenced an aggressive rate-hiking strategy to fight inflation and had raised the cash rate every month between May and December 2022.

Five more rate hikes during 2023 put further pressure on couples with mortgages and put the brakes on family formation. “This combination of the pandemic and rapid economic changes explains the spike and subsequent sharp decline in birth rates we have observed over the past four years,” Mr Rawnsley said.

The impact of high costs of living on couples’ decision to have a baby is highlighted in births data for the capital cities. KPMG estimates there were 60,860 births in Sydney in 2023, down 8.6 percent from 2019. There were 56,270 births in Melbourne, down 7.3 percent. In Perth, there were 25,020 births, down 6 percent, while in Brisbane there were 30,250 births, down 4.3 percent. Canberra was the only capital city where there was no fall in the number of births in 2023 compared to 2019.

“CPI growth in Canberra has been slightly subdued compared to that in other major cities, and the economic outlook has remained strong,” Mr Rawnsley said. “This means families have not been hurting as much as those in other capital cities, and in turn, we’ve seen a stabilisation of births in the ACT.”

This stylish family home combines a classic palette and finishes with a flexible floorplan

Just 55 minutes from Sydney, make this your creative getaway located in the majestic Hawkesbury region.