The Improbably Strong Economy

A lot had to go right for the U.S. to avoid a recession. So far, it has.

The economy is still generating jobs. A year ago, a lot of economists and Federal Reserve policy makers thought that it would be shedding them by now.

On Friday, the Labor Department reported that the U.S. added a seasonally 150,000 jobs in October from the previous month, versus September’s gain of 297,000 jobs. Some of that step down was due to auto workers’ strikes, which have since been resolved but temporarily caused workers to not draw pay checks.

Average hourly earnings rose 0.2% from a month earlier, putting them 4.1% higher than a year earlier. That was the smallest year-over-year gain since June 2021, though unlike then wages are now outpacing inflation.

One takeaway is that the job market is moderating, but not buckling—a message reinforced by a variety of other data, including low levels of weekly unemployment claims and layoffs. Another is that the Federal Reserve is probably through with tightening: Futures markets on Friday morning indicated that the chance of the central bank raising its target range on overnight rates at its December meeting was below 10%. The yield on the 10-year Treasury note, which briefly hit 5% less than two weeks ago, continued to retreat Friday, falling to 4.53% midmorning.

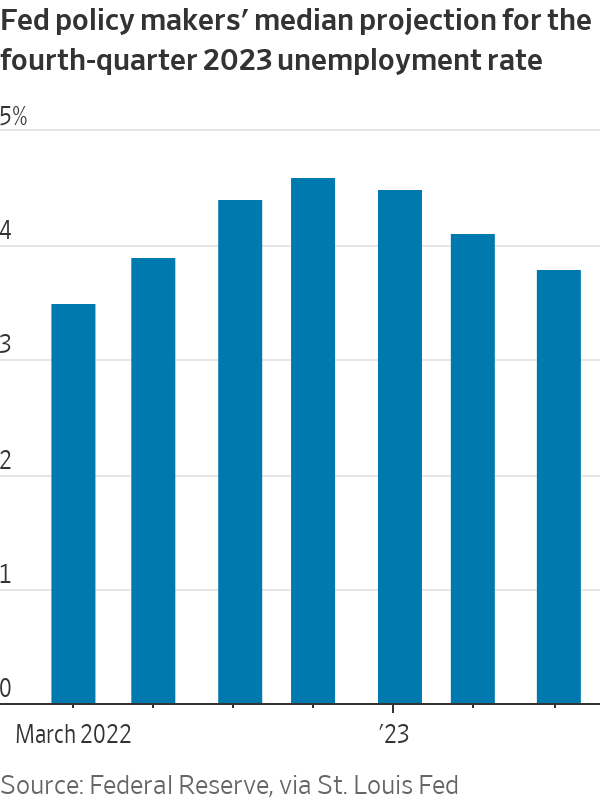

This wasn’t the sort of job market the Fed expected. When policy makers offered projections last December, they forecast that the unemployment rate would average 4.6% in this year’s fourth quarter, versus the 3.7% rate (since revised to 3.6%) they had seen in the November 2022 job report. That was tantamount to a recession forecast, though they didn’t put it that way, since such a large increase in the unemployment rate would count as a strong signal the U.S. is in a downturn. Friday’s report showed the October unemployment rate at 3.9%.

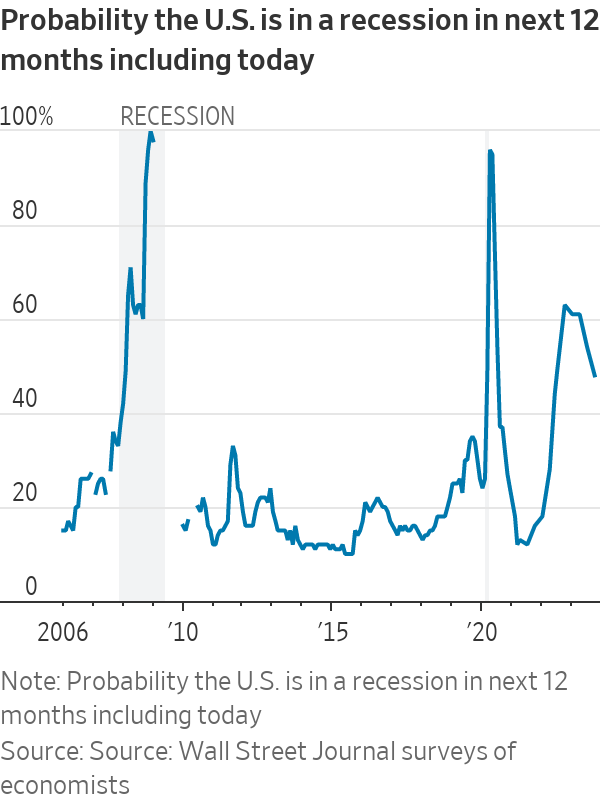

Economists got it wrong, too. In October of last year, forecasters polled by The Wall Street Journal estimated the unemployment rate at the end of 2023 to be at 4.7%, on average. They also put the chances of a recession within the next 12 months at 63%. By last month, they dropped the recession chance to 48%. Available data show that, as a group, economists have never forecast a recession before it has actually started. Now it looks as if the one time they did forecast one, they were either wrong or early.

It is easy to make fun of other people’s past forecasts, but considering the hurdles the economy has had to clear, it really is striking that it has done so well. A year ago there was some hope that the continued recovery in the service sector, and service-sector jobs, might help take up the slack as the goods sector adjusted to slowing demand. But there was also the concern that the service sector could run out of steam before the goods sector found its footing.

Another worry: That the excess savings that Americans had built up after the pandemic struck would run out, and that would cut into their ability to spend. But recent revisions to the available data suggest there was more money left in the tank than thought.

To these, add that inflation has cooled despite the addition of 2.4 million jobs so far this year, and gross domestic product is expanding much faster than economists expected. Plus, at least so far this year, the economy has made it through a regional bank crisis, a sharp increase in both short- and long-term borrowing costs, and the resumption of student-debt payments.

The jury is out on what happens next. The cooling in the job market could turn into a lurch lower, for example, as the full effect of the Fed’s past rate increases begins to take hold. Inflation, which is still too high, could accelerate, prompting the central bank to further tighten the screws.

But the chances of the economy avoiding a recession seem stronger now than they did even a few months ago. A lot of that would be down to luck, but it would nonetheless be something worth celebrating.

Copyright 2020, Dow Jones & Company, Inc. All Rights Reserved Worldwide. LEARN MORE

Copyright 2020, Dow Jones & Company, Inc. All Rights Reserved Worldwide. LEARN MORE

This stylish family home combines a classic palette and finishes with a flexible floorplan

Just 55 minutes from Sydney, make this your creative getaway located in the majestic Hawkesbury region.

Continued stagflation and cost of living pressures are causing couples to think twice about starting a family, new data has revealed, with long term impacts expected

Australia is in the midst of a ‘baby recession’ with preliminary estimates showing the number of births in 2023 fell by more than four percent to the lowest level since 2006, according to KPMG. The consultancy firm says this reflects the impact of cost-of-living pressures on the feasibility of younger Australians starting a family.

KPMG estimates that 289,100 babies were born in 2023. This compares to 300,684 babies in 2022 and 309,996 in 2021, according to the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS). KPMG urban economist Terry Rawnsley said weak economic growth often leads to a reduced number of births. In 2023, ABS data shows gross domestic product (GDP) fell to 1.5 percent. Despite the population growing by 2.5 percent in 2023, GDP on a per capita basis went into negative territory, down one percent over the 12 months.

“Birth rates provide insight into long-term population growth as well as the current confidence of Australian families,” said Mr Rawnsley. “We haven’t seen such a sharp drop in births in Australia since the period of economic stagflation in the 1970s, which coincided with the initial widespread adoption of the contraceptive pill.”

Mr Rawnsley said many Australian couples delayed starting a family while the pandemic played out in 2020. The number of births fell from 305,832 in 2019 to 294,369 in 2020. Then in 2021, strong employment and vast amounts of stimulus money, along with high household savings due to lockdowns, gave couples better financial means to have a baby. This led to a rebound in births.

However, the re-opening of the global economy in 2022 led to soaring inflation. By the start of 2023, the Australian consumer price index (CPI) had risen to its highest level since 1990 at 7.8 percent per annum. By that stage, the Reserve Bank had already commenced an aggressive rate-hiking strategy to fight inflation and had raised the cash rate every month between May and December 2022.

Five more rate hikes during 2023 put further pressure on couples with mortgages and put the brakes on family formation. “This combination of the pandemic and rapid economic changes explains the spike and subsequent sharp decline in birth rates we have observed over the past four years,” Mr Rawnsley said.

The impact of high costs of living on couples’ decision to have a baby is highlighted in births data for the capital cities. KPMG estimates there were 60,860 births in Sydney in 2023, down 8.6 percent from 2019. There were 56,270 births in Melbourne, down 7.3 percent. In Perth, there were 25,020 births, down 6 percent, while in Brisbane there were 30,250 births, down 4.3 percent. Canberra was the only capital city where there was no fall in the number of births in 2023 compared to 2019.

“CPI growth in Canberra has been slightly subdued compared to that in other major cities, and the economic outlook has remained strong,” Mr Rawnsley said. “This means families have not been hurting as much as those in other capital cities, and in turn, we’ve seen a stabilisation of births in the ACT.”

This stylish family home combines a classic palette and finishes with a flexible floorplan

Just 55 minutes from Sydney, make this your creative getaway located in the majestic Hawkesbury region.