The Pay Raise People Say They Need to Be Happy

We frequently overestimate just how much happiness money buys

People are often convinced their lives would improve if only they could climb a few rungs on the income ladder.

They are right, to an extent. Many studies have found a link between income and happiness, both in terms of day-to-day mood and longer-term life satisfaction. Having more money would help many people afford necessities, and on average, richer people report being happier.

Exactly how much more money do we think we need to be happy? A new survey from the financial-services company Empower put the question to about 2,000 people.

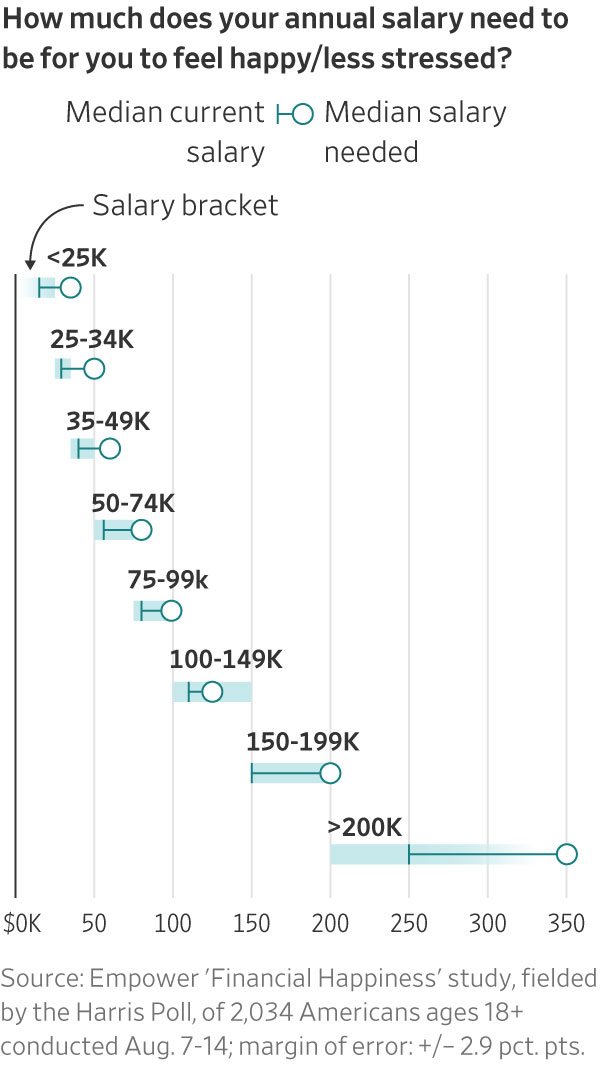

In the survey, most people said it would take a pretty significant pay bump to deliver contentment. The respondents, who had a median salary of $65,000 a year, said a median of $95,000 would make them happy and less stressed. The highest earners, with a median income of $250,000, gave a median response of $350,000.

Employers are planning on an average pay increase of 3.9% in 2024 for nonunion employees, according to a survey from the consulting firm Mercer. In the Empower survey, Americans said that to be happy, they would need almost a 50% raise.

Just how much happier a 3.9% or 50% raise would make any given person is hard to determine, researchers said.

One study, published in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences last year, found that people who randomly received $10,000 tended to get a happiness boost that lasted at least six months. (The $2 million given out in the study was provided by a wealthy couple, who the researchers estimated generated 225 times more happiness than if they had kept the money themselves.)

Another, from the Review of Economic Studies in 2020, looked at lottery winners in Sweden whose prizes were mostly between $100,000 and $500,000. They reported higher levels of satisfaction with their lives more than a decade after their windfall, compared with lottery players who won no prize or a small one.

The magnitude of a raise’s effect, though, might not be life-changing.

“The impact of money on happiness isn’t as large as people typically assume,” said Elizabeth Dunn, a psychology professor at the University of British Columbia and a co-author of a book on money and happiness. “Happiness is determined by so many different factors that changing any one thing, it’s hard to have a huge impact.”

Happiness for sale

About seven in 10 respondents in the Empower survey said they strongly or somewhat agreed with the statement: “Having more money would solve most of my problems.” Similar proportions of people in each income bracket felt that way, including those with salaries of $200,000 or more.

Dunn said that many people might be happier if they focus on the best ways to use the money they have, rather than on getting more of it.

“That’s something that we know makes a difference and that people have control over in the immediate term,” she said.

Dunn said many people over emphasise money, relative to other variables, as a path to contentment. Her research indicates that those who give priority to time over money tend to be happier in life.

A little bit more

And as soon as someone does reach a new pay tier, they often start focusing on the next one as their target recalibrates.

“They might imagine that once they get the higher salary, then that’ll be enough,” said Matt Killingsworth, a senior fellow at the University of Pennsylvania’s Wharton School who studies the causes of happiness. “In reality, once they get there, they’ll probably want a little bit more.”

Even very wealthy people think like this. A 2018 study asked millionaires to rate their happiness on a scale from one to 10 and, if they didn’t say 10, predict how much money they would need to move one point higher. Slightly over half of those with a net worth of $10 million or more said their wealth would need to increase by at least 50%.

“It’s part of what makes humans amazing,” said Killingsworth of the impulse to continue advancing. “But it also means we rarely look at an aspect of our life and say, ‘That’s absolutely perfect.’”

Copyright 2020, Dow Jones & Company, Inc. All Rights Reserved Worldwide. LEARN MORE

Copyright 2020, Dow Jones & Company, Inc. All Rights Reserved Worldwide. LEARN MORE

This stylish family home combines a classic palette and finishes with a flexible floorplan

Just 55 minutes from Sydney, make this your creative getaway located in the majestic Hawkesbury region.

Continued stagflation and cost of living pressures are causing couples to think twice about starting a family, new data has revealed, with long term impacts expected

Australia is in the midst of a ‘baby recession’ with preliminary estimates showing the number of births in 2023 fell by more than four percent to the lowest level since 2006, according to KPMG. The consultancy firm says this reflects the impact of cost-of-living pressures on the feasibility of younger Australians starting a family.

KPMG estimates that 289,100 babies were born in 2023. This compares to 300,684 babies in 2022 and 309,996 in 2021, according to the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS). KPMG urban economist Terry Rawnsley said weak economic growth often leads to a reduced number of births. In 2023, ABS data shows gross domestic product (GDP) fell to 1.5 percent. Despite the population growing by 2.5 percent in 2023, GDP on a per capita basis went into negative territory, down one percent over the 12 months.

“Birth rates provide insight into long-term population growth as well as the current confidence of Australian families,” said Mr Rawnsley. “We haven’t seen such a sharp drop in births in Australia since the period of economic stagflation in the 1970s, which coincided with the initial widespread adoption of the contraceptive pill.”

Mr Rawnsley said many Australian couples delayed starting a family while the pandemic played out in 2020. The number of births fell from 305,832 in 2019 to 294,369 in 2020. Then in 2021, strong employment and vast amounts of stimulus money, along with high household savings due to lockdowns, gave couples better financial means to have a baby. This led to a rebound in births.

However, the re-opening of the global economy in 2022 led to soaring inflation. By the start of 2023, the Australian consumer price index (CPI) had risen to its highest level since 1990 at 7.8 percent per annum. By that stage, the Reserve Bank had already commenced an aggressive rate-hiking strategy to fight inflation and had raised the cash rate every month between May and December 2022.

Five more rate hikes during 2023 put further pressure on couples with mortgages and put the brakes on family formation. “This combination of the pandemic and rapid economic changes explains the spike and subsequent sharp decline in birth rates we have observed over the past four years,” Mr Rawnsley said.

The impact of high costs of living on couples’ decision to have a baby is highlighted in births data for the capital cities. KPMG estimates there were 60,860 births in Sydney in 2023, down 8.6 percent from 2019. There were 56,270 births in Melbourne, down 7.3 percent. In Perth, there were 25,020 births, down 6 percent, while in Brisbane there were 30,250 births, down 4.3 percent. Canberra was the only capital city where there was no fall in the number of births in 2023 compared to 2019.

“CPI growth in Canberra has been slightly subdued compared to that in other major cities, and the economic outlook has remained strong,” Mr Rawnsley said. “This means families have not been hurting as much as those in other capital cities, and in turn, we’ve seen a stabilisation of births in the ACT.”

This stylish family home combines a classic palette and finishes with a flexible floorplan

Just 55 minutes from Sydney, make this your creative getaway located in the majestic Hawkesbury region.