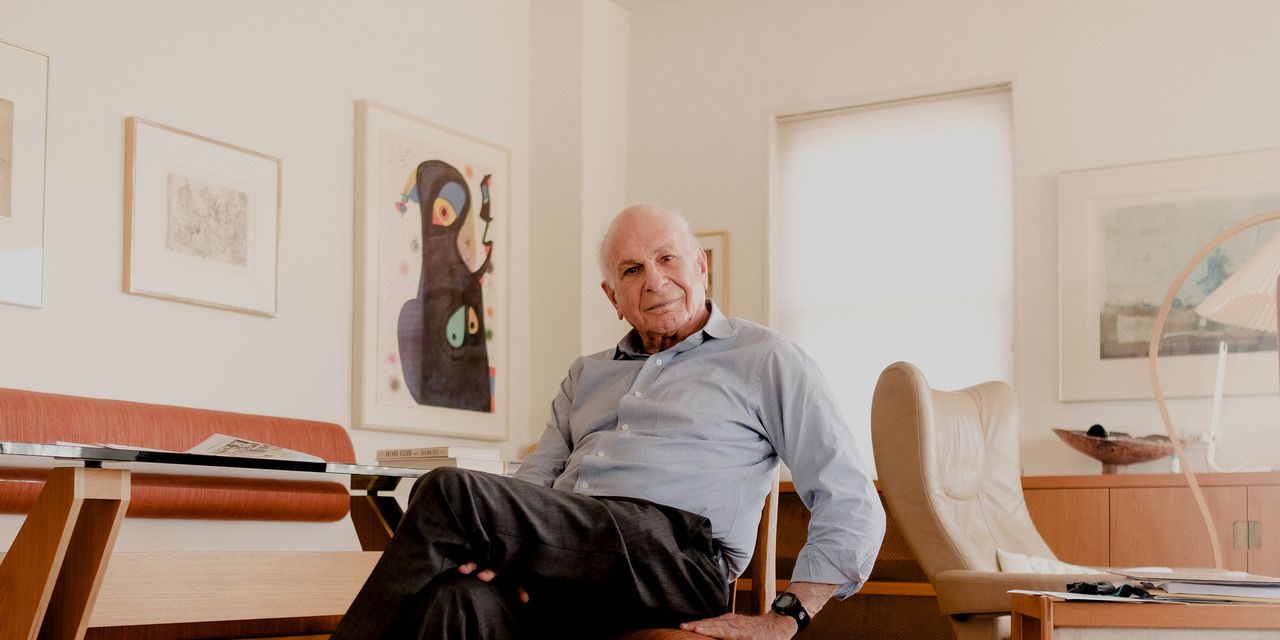

The Psychologist Who Turned the Investing World on Its Head

Daniel Kahneman gave people an understanding of what drives financial decisions

Daniel Kahneman explained investors to themselves.

A psychologist at Princeton University and winner of the Nobel Prize in economics, Kahneman died on March 27, age 90.

Before the pioneering work done by Kahneman and his research partner, Amos Tversky, who died in 1996, economists had assumed that people were “rational,” meaning we are self-interested, use all available information to make unbiased decisions, and our preferences are consistent.

Kahneman and Tversky showed that’s nonsense. Their findings, directly or indirectly, inspired change across the business world, including the redesign of organ-donation programs and improvements in planning for multibillion-dollar infrastructure projects .

Kahneman was a pioneer of what became known as behavioural economics, although he always saw himself as a psychologist. Investors who take Kahneman and Tversky’s lessons to heart can minimise fees, losses and regrets. Kahneman may well have had more influence on investing than anyone else who wasn’t a professional investor.

I first met Danny, as everyone called him, at a conference on behavioral economics in 1996. For years, as an investing journalist, I had wondered: Why are smart people so stupid about money?

About five minutes into Danny’s presentation, I realized he had the answers—not only to that question, but to nearly every mystery of financial behavior.

Why do we sell our winners too soon and hang onto our losers too long? Why don’t we realize that most hot streaks are just luck? Why do we say we have a high tolerance for risk and then suffer the torments of the damned when the market falls? Why do we ignore the odds when we know they’re stacked against us?

Danny paced softly back and forth at the front of the room, his blue-green eyes sparkling with amusement as he documented these behaviors and demolished conventional economic theory.

For decades, he and Tversky had conducted experiments, almost childlike in their simplicity, to see how people really think and behave.

No, Danny said, money lost isn’t the same as money gained. Losses feel at least twice as painful as gains feel pleasant. He asked the conference attendees: If you’d lose $100 on a coin toss if it came up tails, how much would you have to win on heads before you’d take the bet? Most of us said $200 or more.

No, people don’t incorporate all available information. We think short streaks in a random process enable us to predict what comes next. We think jackpots happen more often than they do, making us overconfident. We think disasters are more common than they are, making us suckers for schemes that purport to protect us.

Ask people if they want to take a risk with an 80% chance of success, and most say yes. Ask instead if they’d incur the same risk with a 20% chance of failure, and many say no.

Noting that the stocks people sell outperform the ones they buy, Danny joked that “the cost of having an idea is 4%.”

I wasn’t just struck by his insights; I was stricken by them. I immediately bought all three of the books he had edited. For days, I sat in a windowless room, reading feverishly, red pen in hand, scribbling notes, underlining entire paragraphs, peppering the margins with arrows and exclamation points.

In 2001, a year before Danny won the Nobel, I wrote a long profile of him .

“The most important question to ask before making a decision,” he told me, “is ‘What is the base rate?’”

He meant you should begin every major decision by figuring out the objective odds of success, given the historical range of outcomes in similar situations.

If you’re thinking of starting a new business, your gut might tell you there’s no way you can fail. According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, however, half of new businesses die within the first five years . That base rate comes from millions of startups, each of which also expected to succeed. You, on the other hand, are a sample of one.

Knowing that the base rate is 50/50 shouldn’t deter you from trying, but it should prevent you from being unrealistically optimistic.

Danny knew base rates weren’t quite everything. He told me that before he proposed to his second wife, Anne Treisman, he said to her: “I’m Jewish, you’re not. I’m neurotic, you’re not. Almost half of all marriages end in divorce. The base rates are against us.”

“Oh, who cares about base rates!” she replied. Their marriage lasted four decades; Treisman died in 2018.

In 1969, Danny was teaching at the Hebrew University in Jerusalem when he asked Tversky, a mathematical psychologist and colleague there, to visit his class.

In his guest lecture, Tversky argued humans aren’t that bad at estimating risks and probabilities.

“I just don’t believe it!” exclaimed Danny, who was studying visual perception. He already believed that just as optical illusions fool the eye, cognitive illusions fool the mind.

The two men continued their debate over lunch—and for many years after . Amos was organised, confident, quantitatively brilliant. Danny was untidy, self-doubting, astoundingly intuitive. Together, they were intellectual lightning in a bottle.

In 1971, to decide whose name would be listed as lead author on the first scientific paper they published together, the two men flipped a coin. Over the next quarter-century, they published more than two dozen papers together.

In 2006, Danny asked me to help him write a book . I auditioned for a few months, coming up with several different proposals for how to structure the project. We finally got started in early 2007.

What eventually emerged was “ Thinking, Fast and Slow ,” published late in 2011: an internationally bestselling memoir that also offered an encyclopedic explanation of how the human mind works.

Early on, Danny took me to lunch with his wife near the Princeton campus. When he stepped away, I asked Anne, “Do you think Danny is crazy for wanting to do this book with me?”

“No,” she said. “But you might be crazy for wanting to do it with him.”

In the beginning, I wrote the first drafts of chapters that never saw the light of day. Gradually, Danny took over the writing, agonizing over every sentence, as I rewrote and edited.

Late in 2007, as we were polishing the chapter called “The Illusion of Validity,” I woke up one night in an icy sweat, pulse racing, gasping for air. My wife rushed me to the emergency room. It turned out I hadn’t had a heart attack; I’d had a panic attack, the only one in my life before or since.

Danny was even more alarmed than I was.

In 2008 I moved on, joining The Wall Street Journal. Neither of us would ever publicly discuss our book divorce; Danny finished the final third of the book without me.

“Collaborations don’t always end well,” he’d warned me on our first day of work together, “so I want to make sure you will always think of me as a mensch,” a good person.

And so I do—the most complicated mensch I’ve ever known.

Working on the book exposed me to three of Danny’s qualities I hadn’t previously encountered in their full intensity. Only years later did I realize that I’ve internalized them as a journalist and an investor. Or so I hope.

First, Danny saw everything through a child’s eyes or, as some people call it, “beginner’s mind.” No one else I’ve ever known has so often asked: Why? Instead of assuming the status quo is valid, Danny always started by wondering whether it made any sense.

He was also relentlessly self-critical. I once showed him a letter I’d gotten from a reader telling me—correctly but rudely—that I was wrong about something. “Do you have any idea how lucky you are to have thousands of people who can tell you you’re wrong?” Danny said.

Finally, Danny could rework what we had already done as if it had never existed. Most people hate changing their mind; he liked nothing better, when the evidence justified it. “I have no sunk costs,” he would say.

One of his favorite words, while working on the book, was “miserable.” He used it to describe whatever we had just written; the process of writing a book; and, above all, himself.

Danny’s misery was largely rooted in the decades he and Amos had spent exploring the failings of the human mind by picking apart their own errors of thought and judgment.

Taking the outside view on everything else had given Danny the outside view on himself. He embodied the ultimate form of self-knowledge: to distrust yourself above all.

He knew full well how smart he was, but he also knew how foolish he could be. Noticing that he intuitively stereotyped a bespectacled child as “the young professor,” Danny realized people extrapolate the future from almost no data at all. After buying an expensive apartment, he laughed at knowing that he would also overpay to furnish it.

Born in 1934 in what today is Tel Aviv, Israel, while his mother was visiting there, Danny was raised in France. He spent much of his childhood hiding from the Nazis in barns and chicken coops in the French countryside.

He insisted that didn’t explain much about him; after all, not every survivor of the Holocaust had become a self-critical psychologist fascinated by financial behavior.

Instead, he credited his success to hard work—but even more to luck, especially meeting Tversky.

Danny also insisted that studying the pitfalls and paradoxes of the human mind didn’t make him any better at problem-solving than anybody else: “I’m just better at recognising my mistakes after I make them.”

For all his knowledge of how foolish investors can be, Danny didn’t try to outsmart the market. “I don’t try to be clever at all,” he told me. Most of his money was in index funds. “The idea that I could see what no one else can is an illusion,” he said.

“All of us would be better investors,” he often said, “if we just made fewer decisions.”

Copyright 2020, Dow Jones & Company, Inc. All Rights Reserved Worldwide. LEARN MORE

Copyright 2020, Dow Jones & Company, Inc. All Rights Reserved Worldwide. LEARN MORE

This stylish family home combines a classic palette and finishes with a flexible floorplan

Just 55 minutes from Sydney, make this your creative getaway located in the majestic Hawkesbury region.

Continued stagflation and cost of living pressures are causing couples to think twice about starting a family, new data has revealed, with long term impacts expected

Australia is in the midst of a ‘baby recession’ with preliminary estimates showing the number of births in 2023 fell by more than four percent to the lowest level since 2006, according to KPMG. The consultancy firm says this reflects the impact of cost-of-living pressures on the feasibility of younger Australians starting a family.

KPMG estimates that 289,100 babies were born in 2023. This compares to 300,684 babies in 2022 and 309,996 in 2021, according to the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS). KPMG urban economist Terry Rawnsley said weak economic growth often leads to a reduced number of births. In 2023, ABS data shows gross domestic product (GDP) fell to 1.5 percent. Despite the population growing by 2.5 percent in 2023, GDP on a per capita basis went into negative territory, down one percent over the 12 months.

“Birth rates provide insight into long-term population growth as well as the current confidence of Australian families,” said Mr Rawnsley. “We haven’t seen such a sharp drop in births in Australia since the period of economic stagflation in the 1970s, which coincided with the initial widespread adoption of the contraceptive pill.”

Mr Rawnsley said many Australian couples delayed starting a family while the pandemic played out in 2020. The number of births fell from 305,832 in 2019 to 294,369 in 2020. Then in 2021, strong employment and vast amounts of stimulus money, along with high household savings due to lockdowns, gave couples better financial means to have a baby. This led to a rebound in births.

However, the re-opening of the global economy in 2022 led to soaring inflation. By the start of 2023, the Australian consumer price index (CPI) had risen to its highest level since 1990 at 7.8 percent per annum. By that stage, the Reserve Bank had already commenced an aggressive rate-hiking strategy to fight inflation and had raised the cash rate every month between May and December 2022.

Five more rate hikes during 2023 put further pressure on couples with mortgages and put the brakes on family formation. “This combination of the pandemic and rapid economic changes explains the spike and subsequent sharp decline in birth rates we have observed over the past four years,” Mr Rawnsley said.

The impact of high costs of living on couples’ decision to have a baby is highlighted in births data for the capital cities. KPMG estimates there were 60,860 births in Sydney in 2023, down 8.6 percent from 2019. There were 56,270 births in Melbourne, down 7.3 percent. In Perth, there were 25,020 births, down 6 percent, while in Brisbane there were 30,250 births, down 4.3 percent. Canberra was the only capital city where there was no fall in the number of births in 2023 compared to 2019.

“CPI growth in Canberra has been slightly subdued compared to that in other major cities, and the economic outlook has remained strong,” Mr Rawnsley said. “This means families have not been hurting as much as those in other capital cities, and in turn, we’ve seen a stabilisation of births in the ACT.”

This stylish family home combines a classic palette and finishes with a flexible floorplan

Just 55 minutes from Sydney, make this your creative getaway located in the majestic Hawkesbury region.