Trade Woes in Asia Bring Inflation Relief to U.S. Consumers

But slowing exports to Western nations won’t alone stem rapidly rising prices

SINGAPORE—Sinking global trade is pummelling Asian exports, bringing some relief on inflation to U.S. and other Western consumers.

But easing prices for home furnishings, electronics and other manufactured goods don’t signal high inflation will soon be defeated. Wage growth and services price gains are still elevated. And central banks in the U.S. and Europe are warning they aren’t finished raising interest rates in their fight to cool inflation.

Cheap Asian goods helped keep a lid on price growth for decades before the pandemic. Economists say that phenomenon is unlikely to return with the same intensity now that the high-water mark of globalisation has passed.

Asia’s powerhouse exporters enjoyed a boom in overseas sales during the pandemic as locked-down consumers splurged on new computers, workout gear and home improvements.

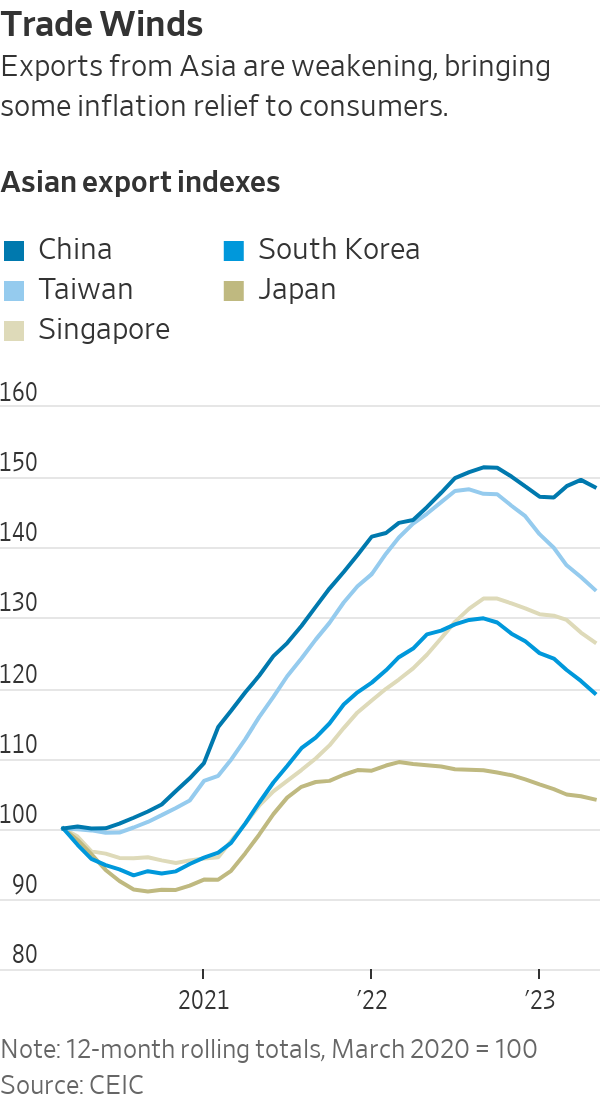

On a rolling 12-month basis, the U.S. dollar value of exports from China, Japan, South Korea, Taiwan and Singapore peaked last year in September at $6.1 trillion. That was 40% higher than recorded over the 12 months through March 2020, when the pandemic began, according to a Wall Street Journal analysis of official figures compiled by data provider CEIC.

Asian exports started sliding late last year as rising interest rates took some heat out of economic growth. Western consumers have slowed spending on goods in favour of eating out, traveling and other services they missed during the pandemic. Hopes that China’s reopening would spur a rebound in trade have fizzled along with the country’s consumer-led recovery.

Exports from South Korea over the 12 months through May were 11% lower than they were in the year through September. Taiwan exports were down 14% over the same period. Singapore’s were down 6%, Japan’s 4% and China’s by 3%.

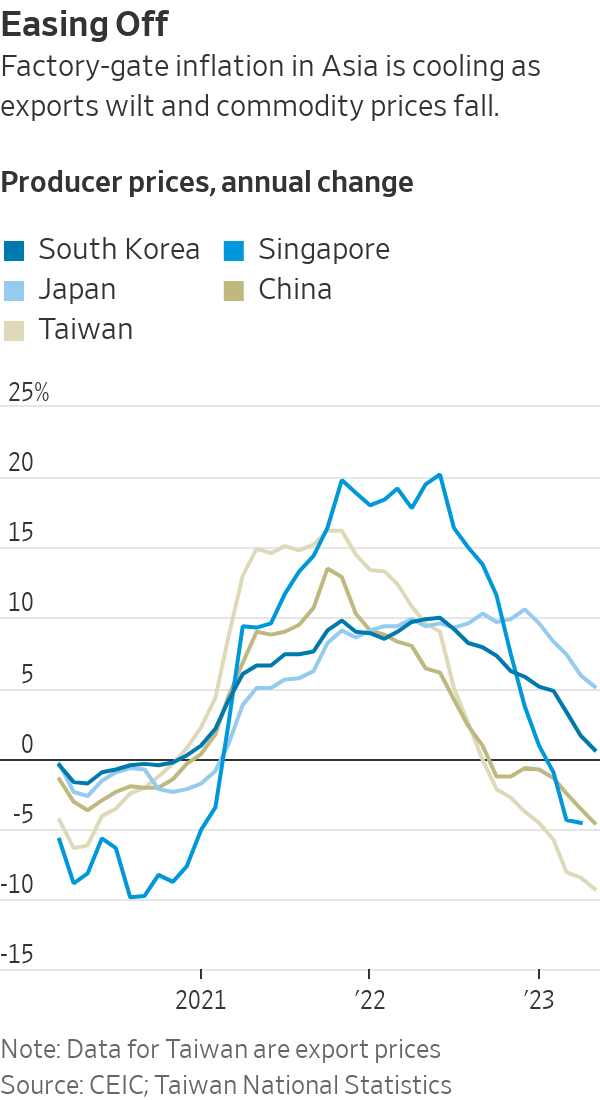

The weakness in trade is showing up in the prices charged for goods when they leave Asia’s factories. Chinese producer prices fell 4.6% in May compared with a year earlier, the eighth straight month of declining supplier prices in the world’s largest factory floor. Similar gauges of inflation in other Asian exporter economies are weakening, too, as lower commodity prices reduce costs and collapsing demand for goods saps companies’ pricing power.

The effects of cooling Asia trade are starting to be felt in the U.S., where the Federal Reserve signalled it expects to further increase interest rates after holding them steady this month.

U.S. import prices for goods from Hong Kong, Singapore, Taiwan and South Korea were down 6.3% in May compared with a year earlier, according to the Labor Department. Import prices were down 2% from China and 3.7% from the Association of Southeast Asian Nations, a 10-member group that includes Indonesia, Malaysia and Thailand.

The prices paid by importers don’t quite line up with the prices faced by consumers, as companies need to cover labor, shipping and other costs to get products into stores.

Nonetheless, prices declined in May from a year earlier for a variety of goods in the U.S. that are often sourced from Asia, including furniture, home appliances, televisions, sports equipment, computers and smartphones.

Overall U.S. inflation is proving resilient, though. The consumer-price index, which measures what Americans pay for goods and services, rose 4% in May from a year earlier—twice the Fed’s 2% goal. Core consumer prices, which exclude food and energy, climbed 5.3%.

If surging prices for goods during the pandemic delivered the first burst of inflation, and rocketing energy prices after Russia invaded Ukraine propelled the second, then the current stickiness of inflation is being fuelled by increases in wages and the price of services. So while easing goods-price inflation is welcome, it doesn’t mean central banks have won the battle, economists say.

“The disinflation impulse coming from Asia is not going to be the magic bullet for the West’s inflation problem,” said Frederic Neumann, chief Asia economist at HSBC in Hong Kong, referring to the slowing pace of price increases.

In the decades before the pandemic, the integration of China into the global economy contributed to a long spell of low and stable inflation enjoyed by many Western economies. The broader integration of markets for goods, services, labor and capital under the banner of globalisation meant cheaper goods for consumers and fewer inflation worries for central banks, though economists debate just how big the effects were.

Now, governments and corporations are tiptoeing away from unfettered globalisation in the interests of security and economic resilience. Manufacturers are adding factories in Vietnam or India while reducing their reliance on China, reflecting concern over icy relations between the U.S.-led West and Beijing. Governments are dangling subsidies in strategic industries such as semiconductors and green-technology products to bring investment and jobs home.

Such trade fractures can increase costs for manufacturers, which, alongside healthier global demand, suggests that inflation in the future won’t be as subdued as it was in the recent past, economists say.

That doesn’t mean globalisation is over or that Asia won’t remain a competitive place to manufacture. But it does mean Asia is unlikely to be as potent a force in tempering price gains as it once was.

“The golden era of globalisation—and the disinflationary pressure associated with that—I think that has gone,” said Neil Shearing, group chief economist at Capital Economics in London.

Copyright 2020, Dow Jones & Company, Inc. All Rights Reserved Worldwide. LEARN MORE

Copyright 2020, Dow Jones & Company, Inc. All Rights Reserved Worldwide. LEARN MORE

This stylish family home combines a classic palette and finishes with a flexible floorplan

Just 55 minutes from Sydney, make this your creative getaway located in the majestic Hawkesbury region.

Continued stagflation and cost of living pressures are causing couples to think twice about starting a family, new data has revealed, with long term impacts expected

Australia is in the midst of a ‘baby recession’ with preliminary estimates showing the number of births in 2023 fell by more than four percent to the lowest level since 2006, according to KPMG. The consultancy firm says this reflects the impact of cost-of-living pressures on the feasibility of younger Australians starting a family.

KPMG estimates that 289,100 babies were born in 2023. This compares to 300,684 babies in 2022 and 309,996 in 2021, according to the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS). KPMG urban economist Terry Rawnsley said weak economic growth often leads to a reduced number of births. In 2023, ABS data shows gross domestic product (GDP) fell to 1.5 percent. Despite the population growing by 2.5 percent in 2023, GDP on a per capita basis went into negative territory, down one percent over the 12 months.

“Birth rates provide insight into long-term population growth as well as the current confidence of Australian families,” said Mr Rawnsley. “We haven’t seen such a sharp drop in births in Australia since the period of economic stagflation in the 1970s, which coincided with the initial widespread adoption of the contraceptive pill.”

Mr Rawnsley said many Australian couples delayed starting a family while the pandemic played out in 2020. The number of births fell from 305,832 in 2019 to 294,369 in 2020. Then in 2021, strong employment and vast amounts of stimulus money, along with high household savings due to lockdowns, gave couples better financial means to have a baby. This led to a rebound in births.

However, the re-opening of the global economy in 2022 led to soaring inflation. By the start of 2023, the Australian consumer price index (CPI) had risen to its highest level since 1990 at 7.8 percent per annum. By that stage, the Reserve Bank had already commenced an aggressive rate-hiking strategy to fight inflation and had raised the cash rate every month between May and December 2022.

Five more rate hikes during 2023 put further pressure on couples with mortgages and put the brakes on family formation. “This combination of the pandemic and rapid economic changes explains the spike and subsequent sharp decline in birth rates we have observed over the past four years,” Mr Rawnsley said.

The impact of high costs of living on couples’ decision to have a baby is highlighted in births data for the capital cities. KPMG estimates there were 60,860 births in Sydney in 2023, down 8.6 percent from 2019. There were 56,270 births in Melbourne, down 7.3 percent. In Perth, there were 25,020 births, down 6 percent, while in Brisbane there were 30,250 births, down 4.3 percent. Canberra was the only capital city where there was no fall in the number of births in 2023 compared to 2019.

“CPI growth in Canberra has been slightly subdued compared to that in other major cities, and the economic outlook has remained strong,” Mr Rawnsley said. “This means families have not been hurting as much as those in other capital cities, and in turn, we’ve seen a stabilisation of births in the ACT.”

This stylish family home combines a classic palette and finishes with a flexible floorplan

Just 55 minutes from Sydney, make this your creative getaway located in the majestic Hawkesbury region.