Why the Drivers of Lower Inflation Matter

Competing effects of central banks, healing supply chains affect recession odds

Recent good news on inflation has ignited a debate over how much central banks’ interest-rate increases are responsible.

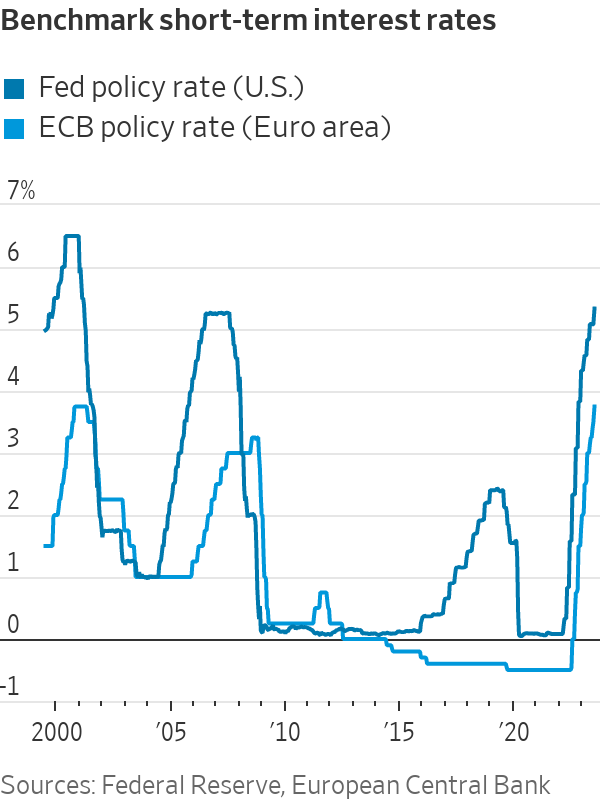

The answer matters for where inflation and interest rates are headed. The Federal Reserve and the European Central Bank in the past week lifted their benchmark interest rates to 22-year highs and left the door open to additional increases.

If higher rates weren’t responsible for the progress on inflation to date, that suggests central banks may be able to lower them before a painful recession sets in.

Central banks generally see their influence on inflation coming through higher rates damping the demand for goods, services and workers, which leads to higher unemployment. That in turn puts downward pressure on prices and wages.

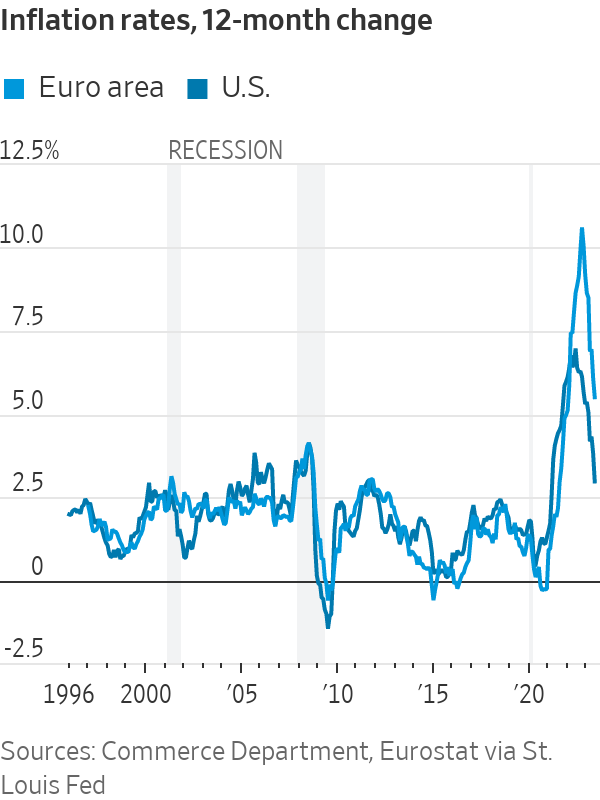

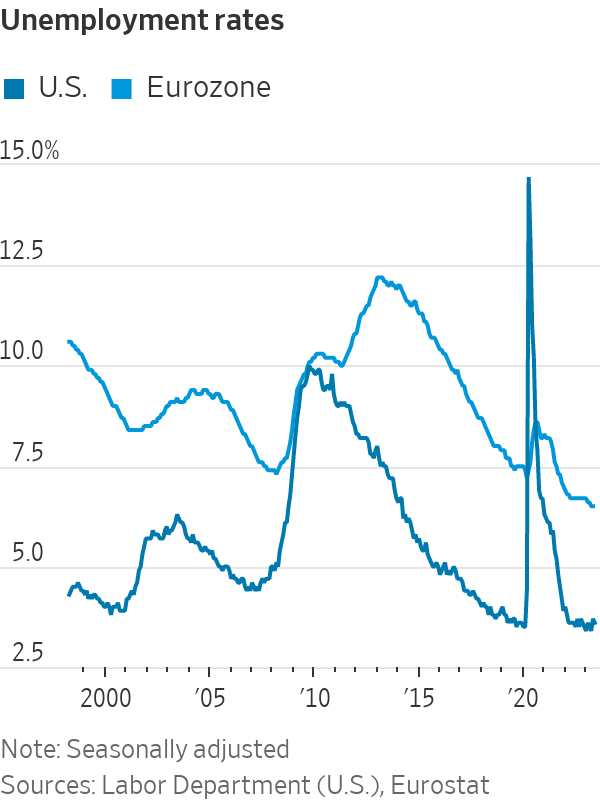

Only the second part of that sequence has occurred. Inflation fell to 3% in the U.S. in June, according to the Fed’s preferred gauge, the personal-consumption expenditures price index, down from 7% one year earlier. Yet the unemployment rate, at 3.6% in June, has held steady for the past year.

In the eurozone, inflation declined to 5.5% in June, the lowest level in nearly 18 months, and unemployment has drifted to the lowest in more than 25 years.

There are competing explanations for this.

One camp argues that inflation has been mostly driven by supply shocks that are going away on their own—much as a postwar surge in the late 1940s unwound by itself. The ripple effects gave the illusion of broader, more persistent price increases.

Take the auto market. Sellers weren’t able to meet pent-up demand two years ago, leading to huge price increases, which in turn spawned higher prices later on for car repairs and auto insurance.

Similarly, a surge in household formation during the pandemic sent up housing prices and rents.

The first camp attributes most of the recent decline in inflation to the ebbing of these one-time supply disruptions, not rate increases, which are supposed to work through the labor market. “It’s calling into question a lot of the old assumptions,” said Lindsay Owens, executive director at the Groundwork Collaborative, a liberal think tank.

A second camp, which includes most economists, disagrees. They say monetary policy kept demand for goods, services, and labor lower than otherwise, taking pressure off strained supply chains and allowing price pressures to ease.

Interest rates can also influence behaviour. The prospect that central bankers would risk a recession to bring down inflation may have influenced expectations of price- and wage-setters, including corporate executives who plan annual budgets for investment and hiring.

Jamie Dimon, chief executive of JPMorgan Chase, warned one year ago of an economic “hurricane” as central banks accelerated rate increases. “You’d better brace yourself,” he said in June 2022, and pledged the bank would be “very conservative” with its balance sheet.

“Inflation is coming down precisely because the Fed avoided more excess demand growth, and they anchored inflation expectations,” said Angel Ubide, head of economic research for global fixed income at Citadel, a hedge-fund firm.

Inflation would be higher now if not for Fed rate increases, “and maybe still rising,” said Karen Dynan, an economist at Harvard University.

In 2021, supply-chain constraints meant even marginal increases in demand led to unusually large price increases. The reverse might be true now: Marginal decreases in demand can bring down prices faster, particularly if more supply is becoming available.

The car market illustrates how monetary policy has been transmitted. Rising rates raised monthly payments, damping demand and robbing sellers of pricing power. In addition, since March, banks appear to be rejecting more car-loan applications.

“That’s leading to a new group of people getting squeezed out of the market, and therefore, it’s playing a role putting downward pressure on prices,” said Julia Coronado, founder of economic-advisory firm MacroPolicy Perspectives.

In Europe, economic growth has stalled since late last year. Business surveys in the past week suggest that growth is weakening sharply, especially in manufacturing, which is most sensitive to interest rates.

The net share of banks reporting increased loan demand declined to a record low in the three months through June, according to an ECB survey of banks. Credit growth to households is the lowest since mid-2016.

Asked at a news conference on Thursday about the transmission of ECB rate increases to growth and inflation, President Christine Lagarde said that in the financial system, “a lot has been transmitted. A lot. We know that. In the economy at large, not as much yet.”

A report published by German insurer Allianz identifies three different forces on the U.S. inflation rate since the second quarter of 2022. Higher inflationary pressures from consumption growth, strong labor markets and government spending added 4 percentage points; fading supply-chain disruptions subtracted five points, and Federal Reserve actions subtracted another five. The net impact was that inflation fell 6 percentage points, whereas it would have fallen only one point without the Fed’s actions.

Fed Chair Jerome Powell said rate increases are “working about as we expect, and we think it’ll play an important role going forward” in bringing down prices for the most labor-intensive services.

Monetary policy has also affected the labor market, but this has shown up in declining job-vacancy rates rather than rising unemployment, some economists say.

Hiring plans in the eurozone services sector are dropping rapidly, according to a survey this month by the European Commission, the European Union’s executive body.

“The labor market is normalising on both sides of the Atlantic, reflecting the impact of higher rates,” said Stefan Gerlach, a former deputy governor of Ireland’s central bank.

The debate over the effect of rate increases also matters for how much further, if at all, central banks need to lift them. Optimists underestimated how much strong demand lifted inflation two years ago. Pessimists may be overestimating the importance of constraining demand to bring it down now.

Gerlach expects inflation to continue declining as higher rates sap demand. “I’m worried central banks have done too much,” he said. “They may have felt embarrassed about having misunderstood inflation the first time.”

Copyright 2020, Dow Jones & Company, Inc. All Rights Reserved Worldwide. LEARN MORE

Copyright 2020, Dow Jones & Company, Inc. All Rights Reserved Worldwide. LEARN MORE

This stylish family home combines a classic palette and finishes with a flexible floorplan

Just 55 minutes from Sydney, make this your creative getaway located in the majestic Hawkesbury region.

Continued stagflation and cost of living pressures are causing couples to think twice about starting a family, new data has revealed, with long term impacts expected

Australia is in the midst of a ‘baby recession’ with preliminary estimates showing the number of births in 2023 fell by more than four percent to the lowest level since 2006, according to KPMG. The consultancy firm says this reflects the impact of cost-of-living pressures on the feasibility of younger Australians starting a family.

KPMG estimates that 289,100 babies were born in 2023. This compares to 300,684 babies in 2022 and 309,996 in 2021, according to the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS). KPMG urban economist Terry Rawnsley said weak economic growth often leads to a reduced number of births. In 2023, ABS data shows gross domestic product (GDP) fell to 1.5 percent. Despite the population growing by 2.5 percent in 2023, GDP on a per capita basis went into negative territory, down one percent over the 12 months.

“Birth rates provide insight into long-term population growth as well as the current confidence of Australian families,” said Mr Rawnsley. “We haven’t seen such a sharp drop in births in Australia since the period of economic stagflation in the 1970s, which coincided with the initial widespread adoption of the contraceptive pill.”

Mr Rawnsley said many Australian couples delayed starting a family while the pandemic played out in 2020. The number of births fell from 305,832 in 2019 to 294,369 in 2020. Then in 2021, strong employment and vast amounts of stimulus money, along with high household savings due to lockdowns, gave couples better financial means to have a baby. This led to a rebound in births.

However, the re-opening of the global economy in 2022 led to soaring inflation. By the start of 2023, the Australian consumer price index (CPI) had risen to its highest level since 1990 at 7.8 percent per annum. By that stage, the Reserve Bank had already commenced an aggressive rate-hiking strategy to fight inflation and had raised the cash rate every month between May and December 2022.

Five more rate hikes during 2023 put further pressure on couples with mortgages and put the brakes on family formation. “This combination of the pandemic and rapid economic changes explains the spike and subsequent sharp decline in birth rates we have observed over the past four years,” Mr Rawnsley said.

The impact of high costs of living on couples’ decision to have a baby is highlighted in births data for the capital cities. KPMG estimates there were 60,860 births in Sydney in 2023, down 8.6 percent from 2019. There were 56,270 births in Melbourne, down 7.3 percent. In Perth, there were 25,020 births, down 6 percent, while in Brisbane there were 30,250 births, down 4.3 percent. Canberra was the only capital city where there was no fall in the number of births in 2023 compared to 2019.

“CPI growth in Canberra has been slightly subdued compared to that in other major cities, and the economic outlook has remained strong,” Mr Rawnsley said. “This means families have not been hurting as much as those in other capital cities, and in turn, we’ve seen a stabilisation of births in the ACT.”

This stylish family home combines a classic palette and finishes with a flexible floorplan

Just 55 minutes from Sydney, make this your creative getaway located in the majestic Hawkesbury region.