Why the Recession Is Always Six Months Away

Continued strong hiring and consumer spending are complicating Federal Reserve Chair Jerome Powell’s campaign to tame inflation.

The next economic downturn has become the most anticipated recession in recent U.S. history. It also keeps getting postponed.

Recent strong hiring and consumer spending are the latest evidence that the pandemic and the unprecedented policy measures that followed are interfering with the Federal Reserve’s campaign to tame inflation.

The government’s stimulus measures left household and business finances in unusually strong shape. Shortages of materials and workers mean companies are still struggling to satisfy demand for rate-sensitive goods, such as homes and autos. And Americans are splurging on labor-intensive activities they avoided in recent years, including dining out, travel and live entertainment.

Wall Street economists began 2023 broadly anticipating a recession by mid-year caused by the weight of the Fed’s rapid interest-rate increases. Some still expect that could happen. Many now think it will take longer to cool the economy and will lead the central bank to raise rates to higher-than-expected levels.

“It’s the ‘Godot’ recession,” said Ray Farris, chief economist at Credit Suisse. Mr. Farris found himself among a small minority of economists last fall who predicted the economy would narrowly skirt a downturn this year. Every six months, economists have predicted a recession six months later, he said. “By the middle of the year, people will still be expecting a recession in six months’ time.”

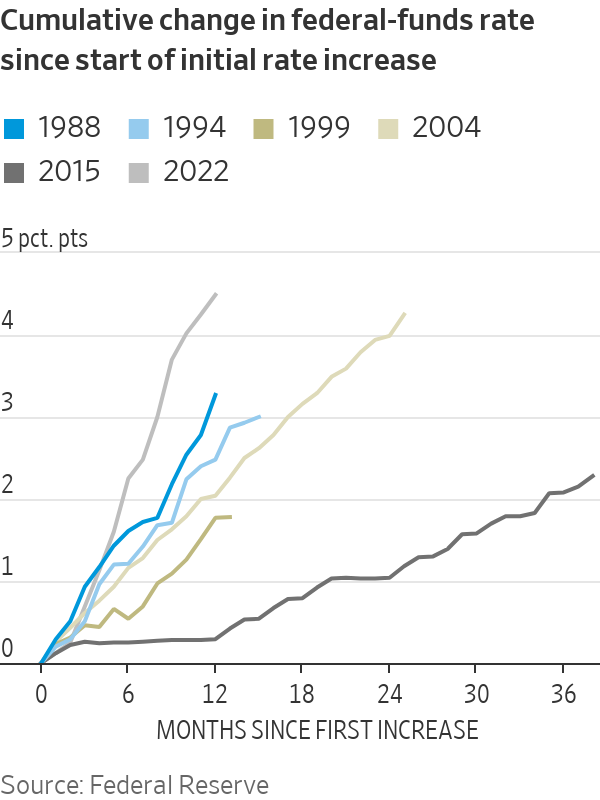

The Fed has been trying to slow investment, spending and hiring to combat inflation by raising rates, which makes it more expensive to borrow and can push down the price of assets such as stocks and real estate. After holding the benchmark federal-funds rate near zero during and after the pandemic, officials lifted the rate more over the past 12 months than any time since the early 1980s, most recently to between 4.5% and 4.75% last month.

The economy’s recent pickup will delay Fed officials’ deliberations about when to pause rate increases. Investors are instead looking for clues about whether they will raise rates by a quarter-percentage-point, as they did last month, or a half-point, as they did in December, at their next meeting, March 21-22.

Fed Chair Jerome Powell is set to begin two days of congressional testimony Tuesday, where he’ll have an opportunity to explain the central bank’s most likely response to a more resilient economy. In December, most Fed officials expected to lift rates this year to between 5% and 5.5%, and officials have indicated those projections could rise at their next meeting.

The economy remains weird

Three factors illustrate the peculiar nature of today’s economic recovery.

First, Washington’s reaction to the initial shock of Covid-19 in March 2020, including holding interest rates at very low levels and showering the economy with cash, left household, business, and local government finances in unusually strong shape.

Through last June, U.S. households had around $1.7 trillion more in savings accumulated through mid-2021 than if income and spending had grown in line with the pre pandemic economy, according to estimates by Fed economists. Even after it is spent, money can still slosh through the economy (one person’s spending is, after all, someone else’s income).

“We are going through the second, third, and fourth-round effects of the initial savings spurred by all these transfer payments during the pandemic,” said Peter Berezin, chief global strategist at BCA Research in Montreal. Rate increases can slow the economy more immediately when expansions are fuelled by credit growth, as opposed to incomes and stimulus, the big drivers of the post-pandemic recovery.

Businesses were able to lock in lower borrowing costs as interest rates plumbed new lows in 2020 and 2021. Just 8% of junk bonds, or those issued by companies without investment-grade ratings, mature over the next two years, according to Goldman Sachs.

Secondly, shortages of materials and workers have made the rate-sensitive housing and auto markets more resilient to higher interest rates—for now. Home builders are resorting heavily to what’s known as buydowns, where they pay to lower the buyer’s mortgage rate for the first year or two. Many current owners are reluctant to sell because they’d have to give up a much lower rate, a phenomenon that is holding for-sale inventories at historically low levels.

Typically when the Fed raises interest rates, demand for housing and cars fall, leading builders and automakers to cut production and lay off workers. This time around, companies are still playing catch-up.

Construction employment hasn’t fallen despite a severe slump in home sales. Builders are still completing homes and apartments started before the Fed increased interest rates. Supply-chain disruptions have extended the amount of time it takes to complete construction. In addition, apartment building ramped up sharply after the pandemic, and those take longer to finish.

In the auto sector, brands of popular fuel-efficient cars are benefitting from pent-up demand after shortages of semiconductor chips kept inventories of new cars at very low levels.

That could make the usual rate-induced slowdown in autos and housing more gradual, said Eric Rosengren, who was president of the Federal Reserve Bank of Boston from 2007 until 2021. “It may take higher interest rates or interest rates higher for longer to get supply and demand back in alignment.”

Thirdly, U.S. consumers, throwing off their pandemic caution, have ramped up spending on services that require lots of workers—think dining out and travel—another example of pent-up demand interfering with the typical business and interest-rate cycle.

Those sectors are often among the first to see demand fall, prompting job cuts, when consumers worry about losing theirs. The easiest way for households to reduce their expenses is to stop eating out and taking vacations.

Consumer spending has enjoyed a rebound in recent months thanks to lower gasoline prices and an additional boost in January from bigger Social Security checks, which are indexed to prior-year inflation. Gas prices jumped last spring after Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. They then steadily declined over the second half last year, easing a cash-crunch for some households that may have offset higher rates on auto loans, credit cards, and mortgages, said economists at Morgan Stanley in a recent report.

Economists at Goldman Sachs said Sunday the Fed could end up raising rates to just below 6% this year if consumer spending runs at higher-than-anticipated levels. That could extend a string of quarter-point rate increases into September.

Labor market conundrum

The labor market sits at the centre of Mr. Powell’s worries about inflation. That’s because steady income growth will sustain consumer spending power and allow companies to keep raising prices.

In the 2000s, then-Fed Chairman Alan Greenspan called it a conundrum that longer-dated bond yields stubbornly refused to rise as the Fed increased rates. For Mr. Powell, the labor market’s strength represents his version of the conundrum. Recession calls keep getting delayed because companies keep hiring and holding on to workers rather than letting them go.

Employers added 517,000 jobs in January, a big figure that shocked economists who were anticipating a slowdown, and pushed the unemployment rate down to 3.4%, a 53-year low. Revisions to earlier reports also pointed to less weakness than initially thought.

The Labor Department’s report on February hiring, due for release Friday, will offer clues as to whether January’s was a one-off blip or a sign of an economy that’s accelerating. A separate report Wednesday could show whether workers continue to quit their jobs at historically high rates, which can indicate greater confidence in their ability to find new jobs with better pay.

Economists at Morgan Stanley estimate that staffing levels across the U.S. are still slightly below what would have been if the pandemic hadn’t hit. They expect that gap to close this year, which could lead hiring rates to slow.

M. Keith Waddell, chief executive of recruiting firm Robert Half International Inc., highlighted a disconnect between a resilient labor market and business surveys that point to signs of easing demand for workers. “Having said that, orders have not dried up,” he said on a Jan. 26 earnings call. “It’s just taking longer to get them closed. Our clients are less urgent. They’re taking more steps. They want to see more candidates.”

Fed officials are in a race to slow down the economy before inflation becomes entrenched. They are also trying to guard against raising rates too much and causing unnecessary economic pain.

Some Fed officials say it could take time to see the effects of their moves, because they had pursued such ultra-stimulative policies until a year ago. Because interest rates have only very recently reached levels that could be considered restrictive, “there is a plausible case to suggest that we’re going to see” more slowing to come, Atlanta Fed President Raphael Bostic told reporters last week.

Business owners report confidence about their own prospects but unease about the broader economic backdrop, said Mr. Bostic. “Everyone is wondering if and when the shoe will drop, but they’re all expecting it to drop for somebody else,” he said.

The need for speed

Uncertainty over when and how much the economy will slow is due in large part to Mr. Powell’s decision to raise interest rates rapidly. The Fed previously spaced out increases, such as in the periods 2004 to 2006 and 2015 to 2018, when lower inflation allowed officials to move more gradually.

The strategy appeared to work because it prevented households and businesses from expecting higher future inflation, which would have kicked off a destructive price spiral, said Kristin Forbes, a professor at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and former member of the Bank of England’s monetary policy committee. Now, the downsides of that strategy are coming into view.

“If you front-load hikes, it makes it harder to tell whether you need to wait a little longer to see the effects, or whether the economy is just more resilient,” she said.

Officials slowed the pace of rises in December and again last month to have more time to study the effects of their past moves. Despite reports of hotter growth and inflation over the past month, Mr. Rosengren sees the slower rate-rise pace as appropriate. “You still are waiting for information about when the previous tightenings are going to have more of an impact,” he said. The timing of a recession “is impossible to predict, but the likelihood remains quite high,” he said.

Since October, the Fed has faced a challenge in which bond investors began to anticipate inflation would fall quickly without a serious downturn. As a result, they expected the Fed would cut rates sooner and faster than central bank officials said they anticipated.

That risked an unhelpful feedback loop for the Fed. While the central bank controls short-term interest rates, long-term rates are influenced by broader market conditions, and they ticked lower between October and February, leading borrowing costs to ease slightly. The 30-year fixed rate mortgage slid to around 6% from 7% last fall.

That has led to a perverse sequence where expectations that the economy will slump are holding down long-term rates, which can stimulate economic activity and make it harder for the economy to slump.

Long-term Treasury yields have since ticked up as investors become more concerned about inflation and stopped believing the Fed would cut rates anytime soon. A big question is whether the run-up in yields will be enough to shift the economy into the slower gear the Fed seeks.

“The Fed needs to get long-term yields high enough to slow the economy,” said Mr. Berezin. “There won’t be a recession until more people are convinced that there won’t be a recession.”

Copyright 2020, Dow Jones & Company, Inc. All Rights Reserved Worldwide. LEARN MORE

Copyright 2020, Dow Jones & Company, Inc. All Rights Reserved Worldwide. LEARN MORE

This stylish family home combines a classic palette and finishes with a flexible floorplan

Just 55 minutes from Sydney, make this your creative getaway located in the majestic Hawkesbury region.

Continued stagflation and cost of living pressures are causing couples to think twice about starting a family, new data has revealed, with long term impacts expected

Australia is in the midst of a ‘baby recession’ with preliminary estimates showing the number of births in 2023 fell by more than four percent to the lowest level since 2006, according to KPMG. The consultancy firm says this reflects the impact of cost-of-living pressures on the feasibility of younger Australians starting a family.

KPMG estimates that 289,100 babies were born in 2023. This compares to 300,684 babies in 2022 and 309,996 in 2021, according to the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS). KPMG urban economist Terry Rawnsley said weak economic growth often leads to a reduced number of births. In 2023, ABS data shows gross domestic product (GDP) fell to 1.5 percent. Despite the population growing by 2.5 percent in 2023, GDP on a per capita basis went into negative territory, down one percent over the 12 months.

“Birth rates provide insight into long-term population growth as well as the current confidence of Australian families,” said Mr Rawnsley. “We haven’t seen such a sharp drop in births in Australia since the period of economic stagflation in the 1970s, which coincided with the initial widespread adoption of the contraceptive pill.”

Mr Rawnsley said many Australian couples delayed starting a family while the pandemic played out in 2020. The number of births fell from 305,832 in 2019 to 294,369 in 2020. Then in 2021, strong employment and vast amounts of stimulus money, along with high household savings due to lockdowns, gave couples better financial means to have a baby. This led to a rebound in births.

However, the re-opening of the global economy in 2022 led to soaring inflation. By the start of 2023, the Australian consumer price index (CPI) had risen to its highest level since 1990 at 7.8 percent per annum. By that stage, the Reserve Bank had already commenced an aggressive rate-hiking strategy to fight inflation and had raised the cash rate every month between May and December 2022.

Five more rate hikes during 2023 put further pressure on couples with mortgages and put the brakes on family formation. “This combination of the pandemic and rapid economic changes explains the spike and subsequent sharp decline in birth rates we have observed over the past four years,” Mr Rawnsley said.

The impact of high costs of living on couples’ decision to have a baby is highlighted in births data for the capital cities. KPMG estimates there were 60,860 births in Sydney in 2023, down 8.6 percent from 2019. There were 56,270 births in Melbourne, down 7.3 percent. In Perth, there were 25,020 births, down 6 percent, while in Brisbane there were 30,250 births, down 4.3 percent. Canberra was the only capital city where there was no fall in the number of births in 2023 compared to 2019.

“CPI growth in Canberra has been slightly subdued compared to that in other major cities, and the economic outlook has remained strong,” Mr Rawnsley said. “This means families have not been hurting as much as those in other capital cities, and in turn, we’ve seen a stabilisation of births in the ACT.”

This stylish family home combines a classic palette and finishes with a flexible floorplan

Just 55 minutes from Sydney, make this your creative getaway located in the majestic Hawkesbury region.