How Hello Kitty Took Over the World

Investors in Sanrio have made 10 times their money as the iconic Japanese brand expands digitally

Hello Kitty is celebrating her 50th birthday this year. Sanrio , the Japanese company behind the iconic character, has much to cheer about too.

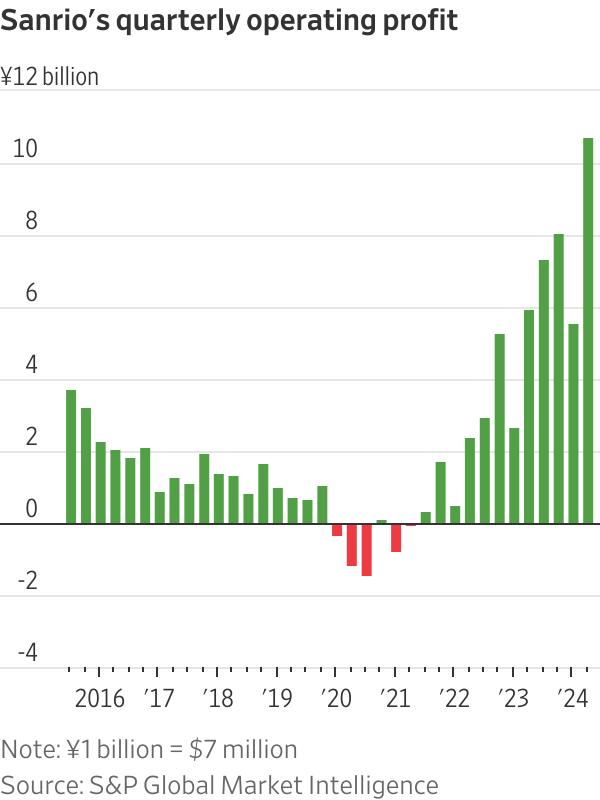

Sanrio’s share price is at a record high after surging 10-fold from its trough in 2020. The company is delivering record profits with strong revenue growth. Operating profit last quarter rose 80% from a year earlier.

Sanrio’s young chief executive, Tomokuni Tsuji —14 years younger than Hello Kitty—probably deserves some applause. He took over the helm from his grandfather in 2020. Sales and profit had been sliding for years when the pandemic arrived. Sanrio had created some of the best-known franchises around the world, but it wasn’t harnessing the full potential of its large portfolio of cute characters.

Tsuji has put younger management in place and finally expanded into the digital world. That includes marketing its characters through social media and other online platforms and ramping up its e-commerce business. It is also expanding its high-margin licensing business, with Sanrio’s characters now gracing products from microwave ovens to sneakers. The licensing business not only is more profitable but also allows more local designs and creates more contact points in overseas markets.

As a result, Sanrio’s business outside of Japan is booming, particularly in China and the U.S. Its profit contribution from abroad, including royalties payment from overseas subsidiaries to the parent company, nearly doubled year on year in the June quarter. Sanrio struck a deal with China’s e-commerce giant Alibaba in 2022 to license its characters in the country. But the U.S. is among its fastest-growing markets: Sales in the Americas grew 141% year on year last quarter. The younger generation is increasingly familiar with Sanrio’s characters given the company’s strong presence on social media.

And the company has also managed to diversify itself away from reliance on Hello Kitty. She has long been Sanrio’s most recognizable character, but the company has developed new characters and done a better job of promoting some existing ones. Hello Kitty accounted for around 30% of Sanrio’s gross profit in product sales and licensing in the fiscal year ended March, compared with 76% a decade earlier. Cinnamoroll, a puppy with white fluffy fur, was voted Sanrio’s top character in an online poll by the company.

The company is also using different types of media to market its characters. It has a Netflix show called “Aggretsuko,” which features an angry red panda struggling with office life, that has been airing for five seasons. A Hello Kitty movie with Warner Bros. is in the making.

Sanrio’s stock now trades at 34 times forward earnings, which isn’t cheap at face value. But if the company can manage to continue its overseas expansion with new characters, it could bring not just cuteness overload, but profit overload too.

Copyright 2020, Dow Jones & Company, Inc. All Rights Reserved Worldwide. LEARN MORE

Copyright 2020, Dow Jones & Company, Inc. All Rights Reserved Worldwide. LEARN MORE

A divide has opened in the tech job market between those with artificial-intelligence skills and everyone else.

A 30-metre masterpiece unveiled in Monaco brings Lamborghini’s supercar drama to the high seas, powered by 7,600 horsepower and unmistakable Italian design.

A divide has opened in the tech job market between those with artificial-intelligence skills and everyone else.

There has rarely, if ever, been so much tech talent available in the job market. Yet many tech companies say good help is hard to find.

What gives?

U.S. colleges more than doubled the number of computer-science degrees awarded from 2013 to 2022, according to federal data. Then came round after round of layoffs at Google, Meta, Amazon, and others.

The Bureau of Labor Statistics predicts businesses will employ 6% fewer computer programmers in 2034 than they did last year.

All of this should, in theory, mean there is an ample supply of eager, capable engineers ready for hire.

But in their feverish pursuit of artificial-intelligence supremacy, employers say there aren’t enough people with the most in-demand skills. The few perceived as AI savants can command multimillion-dollar pay packages. On a second tier of AI savvy, workers can rake in close to $1 million a year .

Landing a job is tough for most everyone else.

Frustrated job seekers contend businesses could expand the AI talent pipeline with a little imagination. The argument is companies should accept that relatively few people have AI-specific experience because the technology is so new. They ought to focus on identifying candidates with transferable skills and let those people learn on the job.

Often, though, companies seem to hold out for dream candidates with deep backgrounds in machine learning. Many AI-related roles go unfilled for weeks or months—or get taken off job boards only to be reposted soon after.

Playing a different game

It is difficult to define what makes an AI all-star, but I’m sorry to report that it’s probably not whatever you’re doing.

Maybe you’re learning how to work more efficiently with the aid of ChatGPT and its robotic brethren. Perhaps you’re taking one of those innumerable AI certificate courses.

You might as well be playing pickup basketball at your local YMCA in hopes of being signed by the Los Angeles Lakers. The AI minds that companies truly covet are almost as rare as professional athletes.

“We’re talking about hundreds of people in the world, at the most,” says Cristóbal Valenzuela, chief executive of Runway, which makes AI image and video tools.

He describes it like this: Picture an AI model as a machine with 1,000 dials. The goal is to train the machine to detect patterns and predict outcomes. To do this, you have to feed it reams of data and know which dials to adjust—and by how much.

The universe of people with the right touch is confined to those with uncanny intuition, genius-level smarts or the foresight (possibly luck) to go into AI many years ago, before it was all the rage.

As a venture-backed startup with about 120 employees, Runway doesn’t necessarily vie with Silicon Valley giants for the AI job market’s version of LeBron James. But when I spoke with Valenzuela recently, his company was advertising base salaries of up to $440,000 for an engineering manager and $490,000 for a director of machine learning.

A job listing like one of these might attract 2,000 applicants in a week, Valenzuela says, and there is a decent chance he won’t pick any of them. A lot of people who claim to be AI literate merely produce “workslop”—generic, low-quality material. He spends a lot of time reading academic journals and browsing GitHub portfolios, and recruiting people whose work impresses him.

In addition to an uncommon skill set, companies trying to win in the hypercompetitive AI arena are scouting for commitment bordering on fanaticism .

Daniel Park is seeking three new members for his nine-person startup. He says he will wait a year or longer if that’s what it takes to fill roles with advertised base salaries of up to $500,000.

He’s looking for “prodigies” willing to work seven days a week. Much of the team lives together in a six-bedroom house in San Francisco.

If this sounds like a lonely existence, Park’s team members may be able to solve their own problem. His company, Pickle, aims to develop personalised AI companions akin to Tony Stark’s Jarvis in “Iron Man.”

Overlooked

James Strawn wasn’t an AI early adopter, and the father of two teenagers doesn’t want to sacrifice his personal life for a job. He is beginning to wonder whether there is still a place for people like him in the tech sector.

He was laid off over the summer after 25 years at Adobe , where he was a senior software quality-assurance engineer. Strawn, 55, started as a contractor and recalls his hiring as a leap of faith by the company.

He had been an artist and graphic designer. The managers who interviewed him figured he could use that background to help make Illustrator and other Adobe software more user-friendly.

Looking for work now, he doesn’t see the same willingness by companies to take a chance on someone whose résumé isn’t a perfect match to the job description. He’s had one interview since his layoff.

“I always thought my years of experience at a high-profile company would at least be enough to get me interviews where I could explain how I could contribute,” says Strawn, who is taking foundational AI courses. “It’s just not like that.”

The trouble for people starting out in AI—whether recent grads or job switchers like Strawn—is that companies see them as a dime a dozen.

“There’s this AI arms race, and the fact of the matter is entry-level people aren’t going to help you win it,” says Matt Massucci, CEO of the tech recruiting firm Hirewell. “There’s this concept of the 10x engineer—the one engineer who can do the work of 10. That’s what companies are really leaning into and paying for.”

He adds that companies can automate some low-level engineering tasks, which frees up more money to throw at high-end talent.

It’s a dynamic that creates a few handsomely paid haves and a lot more have-nots.

A cluster of century-old warehouses beneath the Harbour Bridge has been transformed into a modern workplace hub, now home to more than 100 businesses.

A divide has opened in the tech job market between those with artificial-intelligence skills and everyone else.