Does Sustainable Investing Really Help the Environment?

Experts argue whether green investing is benefitting Wall Street or the planet.

Sustainable investing has been a wild success. For Wall Street, at least.

Mutual funds and exchange-traded funds that focus on ESG (environmental, social, and governance issues) have made a lot of money for investment firms. Investors worried about climate change, in particular, have poured money into such funds, even though the funds charge higher fees than standard funds. More money is expected to flow in. The Labor Department has proposed a rule that would make it easier for investors to buy ESG funds in their 401(k) plans.

For some investors, it is purely a financial bet on a popular sector. Many others are hoping that the billions of dollars flowing into ESG will create positive change for the environment and other causes. But whether Wall Street or Mother Nature will be the ultimate beneficiary of all of these ESG dollars is a difficult question to answer.

We asked two experts to weigh in.

Tariq Fancy, chief executive officer of the Rumie Initiative, an education-technology nonprofit, has been a critic of ESG investing since leaving his job as chief investment officer for sustainable investing at BlackRock. Mr. Fancy says that much needs to be done to address climate change and prevent environmental disasters in the future. He says he doesn’t believe that ESG investing and financial products associated with it are a real help in achieving those goals. In his writings, including an online essay in August, “The Secret Diary of a Sustainable Investor,” he argues that funds that focus on ESG issues are profitable for Wall Street—but amount to a “dangerous placebo” that doesn’t cure the planet’s problems.

Alex Edmans, professor of finance at London Business School and an adviser on responsible investing to Royal London Asset Management and other investment firms, disagrees that the investing efforts represented by ESG funds and other private-investment-based strategies are as pointless as Mr. Fancy says. Dr. Edmans says that while he sees merit in some of Mr. Fancy’s criticisms, they are more sweeping and blanket than justified.

Here are edited excerpts of their discussion, conducted by email:

WSJ:You both have been advocates of sustainable investing, though you disagree about Wall Street’s role. Overall, do you feel better about the fate of the planet now that Wall Street has carved a niche for ESG?

MR. FANCY: Unfortunately, I feel worse about it. Is ESG good for the industry? Undoubtedly yes. It presents a lucrative new opportunity to raise funds and fees. And as an added bonus, it keeps government regulation to address the climate crisis at bay through feeding us yet another narrative in which our answers are solved by the “free market” magically self-correcting.

But good for the planet? I think even Alex would agree that there is no compelling empirical evidence that ESG investing mitigates climate change. Outside of a very small minority of private, long-term funds, such as venture-capital funds that back promising technological solutions to the climate crisis, the vast majority of funds marketed as ESG and sustainable funds today—as well as the nonbinding practice of ESG integration into existing investment processes—can’t point to any real-world impact that would not have otherwise occurred.

DR. EDMANS: I feel modestly better about it. Only modestly better, because Tariq is right that divestment has a negligible effect on company behaviour. But still better, because Tariq’s essay in August ignored the key mechanism through which sustainable investing has impact—engaging with companies on ESG issues. We’ve seen such impact with upstart hedge fund Engine No. 1 getting three climate-conscious directors appointed to Exxon’s board, and this isn’t just an isolated case. Indeed, careful research shows that engagement by index funds, hedge funds and investor collective-action groups creates shared value for both shareholders and society. In particular, activism on ESG issues creates shareholder value as a byproduct, and activism to enhance long-term shareholder value ends up improving ESG.

MR. FANCY: Given the scale of the challenge presented by the climate crisis, we need to stay focused on the bigger picture: The ESG industry may be developing data sets, standards, and ushering in a wave of talented young people to work with them, but these tools are clearly not being combined in the right way right now—given that ESG assets and marketing spin are increasing rapidly alongside carbon emissions, inequality and a host of problems they’re meant to do something about. Are there a few isolated areas where ESG can create win-wins? Sure. But overall, the ESG industry today consists of products that have higher fees but little or no impact and narratives that mislead the public and delay the government reforms we need.

The small wins that Alex highlights, insofar as they exist, are nowhere near sufficient to rapidly decarbonize our economy on the timeline required, which only governments can catalyze through rapidly adjusting the incentives of all the players in the system, for example through a price on carbon. I refer to ESG’s small, mainly marketing wins as “giving wheatgrass to a cancer patient.” And there is now evidence emerging that they may be a giant societal placebo that lowers the likelihood of us following expert recommendations to address the climate crisis. In that sense, the wheatgrass isn’t harmless; it’s delaying the chemotherapy that science tells us we need immediately.

If you sell people a win-win fantasy, they’re less likely to accept the truth: Fighting climate change is going to require an economic transformation that will of course 100% involve the private sector, but must be sparked by government, including through taxes and regulation, and is going to be very difficult and cost us a lot of money.

WSJ:Dr. Edmans, you seem to have more faith than Mr. Fancy in the role of investors in helping the planet.

DR. EDMANS: Tariq is correct that government intervention is key. However, it’s not either/or. Investors launching sustainable funds does not prevent government action; in contrast, doing so encourages action by shifting the so-called Overton window—the range of ideas that is currently acceptable in the political mainstream. Moreover, many investors directly call for government action. In July, investors representing over $6 trillion in assets called for a global carbon price.

MR. FANCY: The only people shifting the Overton window toward a robust response to the climate crisis are brave activists, climate scientists, climate economists and other experts who are telling us that saving the planet will involve taking sacrifices, and needs to happen quickly. The Overton window wasn’t shifted by the ESG industry; on the contrary, today it’s unfortunately being wasted by it by diverting the growing momentum for climate action into yet another dodgy free-markets-self-correct fable.

WSJ: Mr. Fancy in his August essay made the analogy that capitalism is like a basketball game: Each is a competition to score (whether points or profits), and sportsmanship happens only when it’s required under the rules. The implication is that Wall Street doesn’t really have its heart in helping the planet.

DR. EDMANS: Many ESG advocates immediately got on the defensive and started arguing why Tariq’s essay is wrong. But we should first consider the possibility that it might be right. Relying on companies/investors to do the right thing without government action is as naive as having a professional basketball league without rules or referees, but clubs writing glossy purpose statements promising to play fair.

However, the analogy is imperfect in two ways. First, basketball is a zero-sum game. One team can only win if the other loses, and so instances of sportsmanship will be limited. But, in many cases, business is a positive-sum game. Rigorous evidence shows that “sportsmanship” to your stakeholders can also benefit shareholders, so it’s in investors’ own interest to take stakeholders seriously. For example, companies that treat their employees well outperformed their peers in total shareholder returns by a range of 2.3 to 3.8 percentage points a year over a 28-year period—that’s 89 points to 184 compounded. Similar results hold for companies that deliver value to customers, the environment and material stakeholders. Second, many key ESG dimensions can’t be regulated, such as corporate culture—hence the role for investors to hold companies to account.

There are certainly institutional investors who claim that their sustainability actions are a substitute for government action, and who launch ESG products with bold claims of impact to dupe unsuspecting clients to pay fat fees for them. Tariq’s essay has a lot of value in calling them out. However, most true ESG investors don’t do this. They don’t make unsupported claims of impact; their marketing argues that ESG’s main effect is to improve long-term returns rather than change company behaviour. Investors who are late to the ESG game are suddenly jumping on the bandwagon and making a lot of noise in a desperate attempt to play catch-up. Tariq is right to expose them, just like those who promote faddish weight-loss programs should be exposed—but this doesn’t mean the entire weight-loss industry is a ruse.

MR. FANCY: There are indeed areas where small win-wins exist, and where shareholder value can be enhanced by serving all stakeholders. I used to eagerly trumpet these areas in my previous role in sustainable investing. I’ve received an avalanche of messages from people thanking me for saying something they also felt needed to be said. Yet few want to say that out loud themselves, which I understand: I couldn’t have said the same things while I was still in the industry.

I think the ESG industry has the potential to move from serving as a dangerous placebo to playing a leading role in this change, but that requires us having an open and honest debate about how to arrive at a more rigorous and honest ESG 2.0.

Copyright 2020, Dow Jones & Company, Inc. All Rights Reserved Worldwide. LEARN MORE

Copyright 2020, Dow Jones & Company, Inc. All Rights Reserved Worldwide. LEARN MORE

This stylish family home combines a classic palette and finishes with a flexible floorplan

Just 55 minutes from Sydney, make this your creative getaway located in the majestic Hawkesbury region.

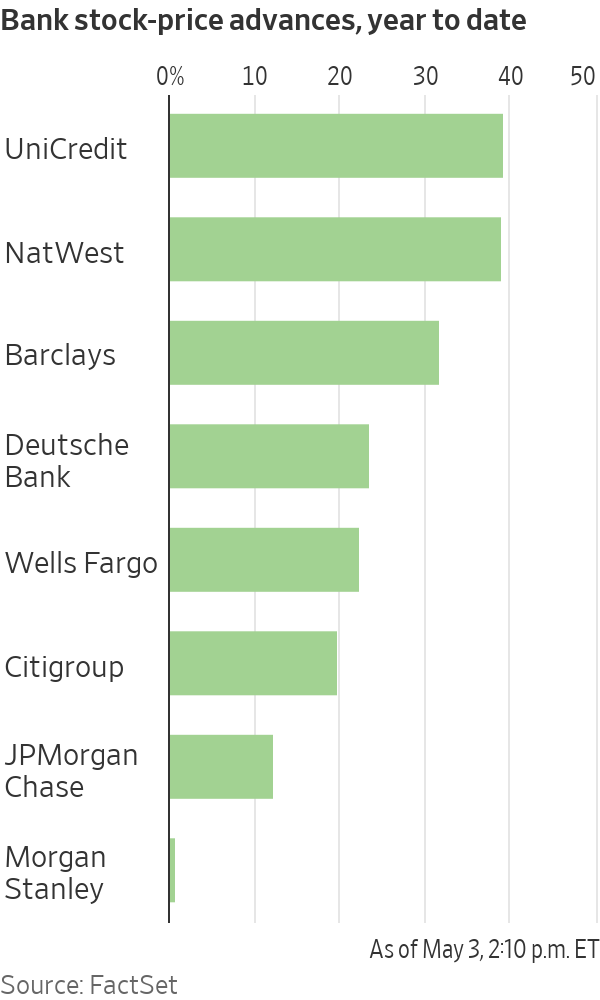

Shares in European banks such as UniCredit have been on a tear

After years in the doldrums, European banks have cleaned up their balance sheets, cut costs and started earning more on loans.

The result: Stock prices have surged and lenders are preparing to hand back some $130 billion to shareholders this year. Even dealmaking within the sector, long a taboo topic, is back, with BBVA of Spain resurrecting an approach for smaller rival Sabadell .

The resurgence is enriching a small group of hedge funds and others who started building contrarian bets on European lenders when they were out of favour. Beneficiaries include hedge-fund firms such as Basswood Capital Management and so-called value investors such as Pzena Investment Management and Smead Capital Management.

It is also bringing in new investors, enticed by still-depressed share prices and promising payouts.

“There’s still a lot of juice left to squeeze,” said Bennett Lindenbaum, co-founder of Basswood, a hedge-fund firm based in New York that focuses on the financial sector.

Basswood began accumulating positions around 2018. European banks were plagued by issues including political turmoil in Italy and money-laundering scandals . Meanwhile, negative interest rates had hammered profits.

Still, Basswood’s team figured valuations were cheap, lenders had shored up capital and interest rates wouldn’t stay negative forever. The firm set up a European office and scooped up stock in banks such as Deutsche Bank , UniCredit and BNP Paribas .

Fast forward to 2024, and European banking stocks are largely beating big U.S. banks this year. Shares in many, such as Germany’s largest lender Deutsche Bank , have hit multiyear highs .

A long-only version of Basswood’s European banks and financials strategy—which doesn’t bet on stocks falling—has returned approximately 18% on an annualised basis since it was launched in 2021, before fees and expenses, Lindenbaum said.

The industry’s turnaround reflects years spent cutting costs and jettisoning bad loans, plus tougher operating rules that lifted capital levels. That meant banks were primed to profit when benchmark interest rates turned positive in 2022.

On a key measure of profitability, return on equity, the continent’s 20 largest banks overtook U.S. counterparts last year for the first time in more than a decade, Deutsche Bank analysts say.

Reflecting their improved health, European banks could spend almost as much as 120 billion euros, or nearly $130 billion, on dividends and share buybacks this year, according to Bank of America analysts.

If bank mergers pick up, that could mean takeover offers at big premiums for investors in smaller lenders. European banks were so weak for so long, dealmaking stalled. Acquisitive larger banks like BBVA could reap the rewards of greater scale and cost efficiencies, assuming they don’t overpay.

“European banks, in general, are cheaper, better capitalised, more profitable and more shareholder friendly than they have been in many years. It’s not surprising there’s a lot of new investor interest in identifying the winners in the sector,” said Gustav Moss, a partner at the activist investor Cevian Capital, which has backed institutions including UBS .

As central banks move to cut interest rates, bumper profits could recede, but policy rates aren’t likely to return to the negative levels banks endured for almost a decade. Stock prices remain modest too, with most far below the book value of their assets.

Among the biggest winners are investors in UniCredit . Shares in the Italian lender have more than quadrupled since Andrea Orcel became chief executive in 2021, reaching their highest levels in more than a decade.

Under the former UBS banker, UniCredit has boosted earnings and started handing large sums back to shareholders , after convincing the European Central Bank the business was strong enough to make large payouts.

Orcel said European banks are increasingly attracting investors like hedge funds with a long-term view, and with more varied portfolios, like pension funds.

He said that investor-relations staff initially advised him that visiting U.S. investors was important to build relationships—but wasn’t likely to bear fruit, given how they viewed European banks. “Now Americans ask you for meetings,” Orcel said.

UniCredit is the second-largest position in Phoenix-based Smead Capital’s $126 million international value fund. It started investing in August 2022, when UniCredit shares traded around €10. They now trade at about €35.

Cole Smead , the firm’s chief executive, said the stock has further to run, partly because UniCredit can now consider buying rivals on the cheap.

Sentiment has shifted so much that for some investors, who figure the biggest profits are to be made betting against the consensus, it might even be time to pull back. A recent Bank of America survey found regional investors had warmed to European banks, with 52% of respondents judging the sector attractive.

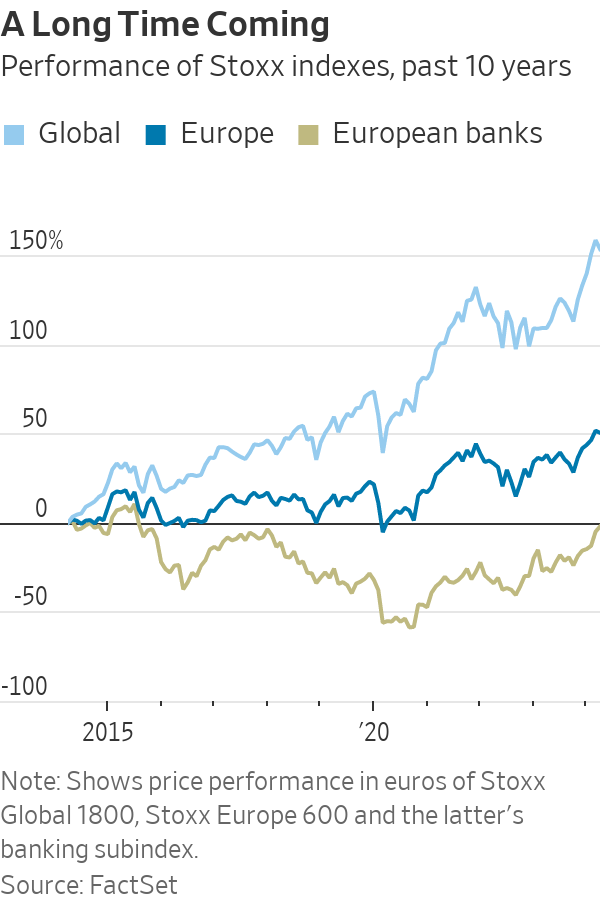

And while bets on banks are now paying off, trying to bottom-fish in European banking stocks has burned plenty of investors over the past decade. Investments have tied up money that could have made far greater returns elsewhere.

Deutsche Bank, for instance, underwent years of scandals and big losses before stabilising under Chief Executive Christian Sewing . Rewarding shareholders, he said, is now the bank’s priority.

U.S. private-equity firm Cerberus Capital Management built stakes in Deutsche Bank and domestic rival Commerzbank in 2017, only to sell a chunk when shares were down in 2022. The investor struggled to make changes at Commerzbank.

A Cerberus spokesman said it remains “bullish and committed to the sector,” with bank investments in Poland and France. It retains shares in both Deutsche and Commerzbank, and is an investor in another German lender, the unlisted Hamburg Commercial Bank.

Similarly, Capital Group also invested in both Deutsche Bank and Commerzbank, only to sell roughly 5% stakes in both banks in 2022—at far below where they now trade. Last month, Capital Group disclosed buying shares again in Deutsche Bank, lifting its holding above 3%. A spokeswoman declined to comment.

U.S.-based Pzena, which manages some $64 billion in assets, has backed banks such as UBS and U.K.-listed HSBC , NatWest and Barclays .

Pzena reckoned balance sheets, capital positions and profitability would all eventually improve, either through higher interest rates or as business models shifted. Still, some changes took longer than expected. “I don’t think anyone would have thought the ECB would keep rates negative for eight or nine years,” said portfolio manager Miklos Vasarhelyi.

Some Pzena investments date as far back as 2009 and 2010, Vasarhelyi said. “We’ve been waiting for this to turn for a long time.”

This stylish family home combines a classic palette and finishes with a flexible floorplan

Consumers are going to gravitate toward applications powered by the buzzy new technology, analyst Michael Wolf predicts