Americans in Their Prime Are Flooding Into the Job Market

Share of people between 25 and 54 working or seeking jobs rose this year to highest level since 2002

The core of the American labour force is back.

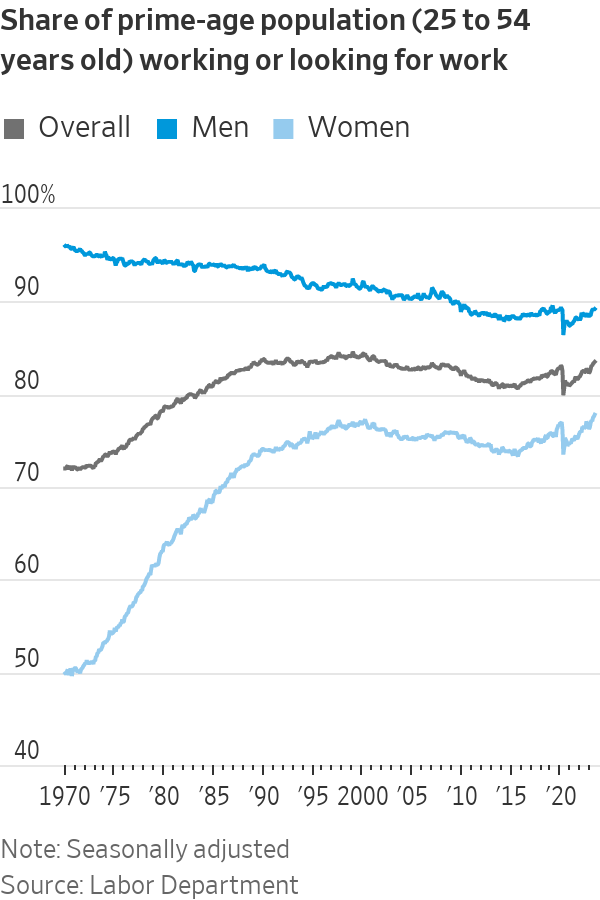

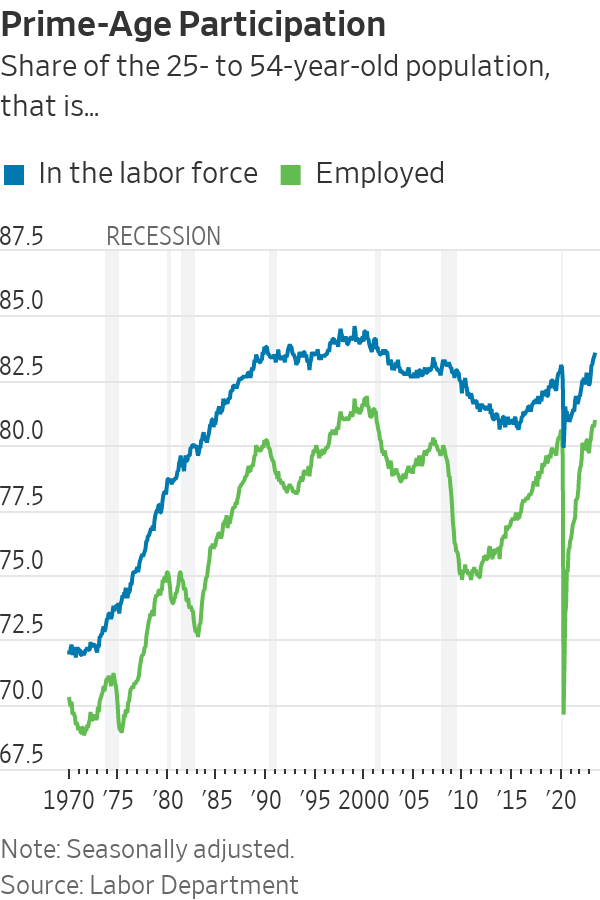

Americans between 25 and 54 years of age are either employed or looking for jobs at rates not seen in two decades, a trend helping to counter the exodus of older baby boomers from the workforce. Economists define that age range as in their prime working years—when most Americans are done with their formal education, aren’t ready to retire and tend to be most attached to the labor force.

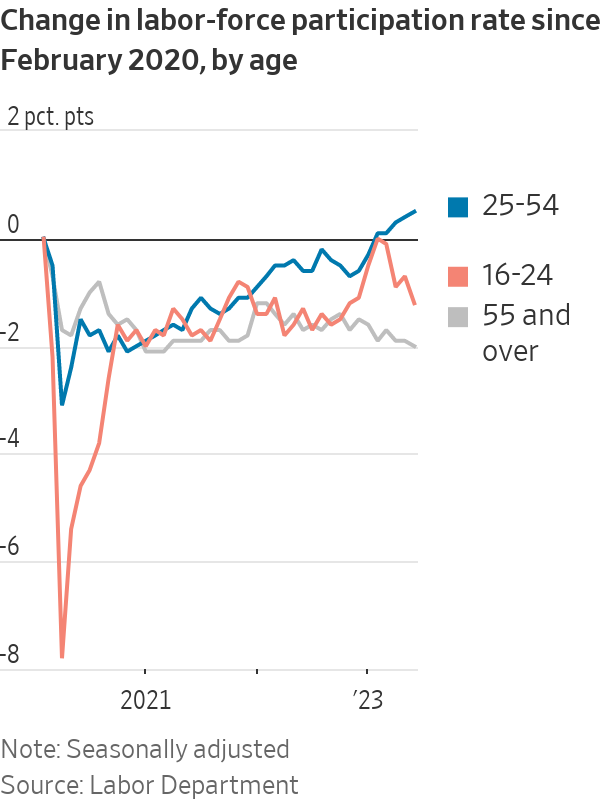

In the first months of the pandemic, nearly four million prime-age workers left the labor market, pushing participation in early 2020 to the lowest level since 1983—before women had become as much of a force in the workplace. Prime-age workers now exceed pre pandemic levels by almost 2.2 million.

That growth is taking a little heat out of the job market and could help the Federal Reserve’s efforts to tamp down inflation by keeping wage growth in check.

Women lead the way

The resurgence of mid career workers is driven by women taking jobs.

The labor-force participation rate for prime-age women was the highest on record, 77.8% in June. That is well up from 73.5% in April 2020.

Men, however, tend to be employed at higher rates. The overall prime-age participation rate rose in June to 83.5%, the highest since 2002.

The big draw: a tight labor market. The unemployment rate has hovered near a half-century low for more than a year, and job openings outnumber the ranks of unemployed. Employers can’t be as choosy or selective, William Rodgers, vice president and director of the Institute for Economic Equity at the St. Louis Fed, said earlier this month.

Employers “are more apt to be willing to work with candidates—in this case it’s working with moms, or parents in general,” he said. “Tight labor markets can help to punish those who discriminate in hiring and compensation.”

Other factors are also at play. Women aren’t having as many children—there were about 3.66 million births in 2022, 655,000 fewer than the peak in 2007—so child-care responsibilities have decreased.

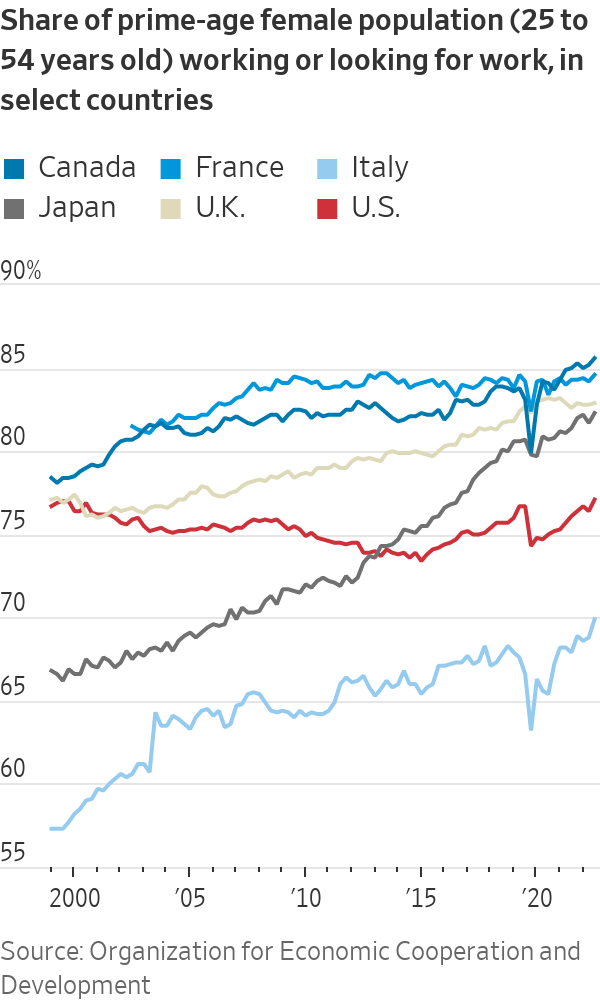

Julia Pollak, chief economist at ZipRecruiter, said it is possible for women’s participation to rise further if employers adopt or the government requires additional family-friendly policies. U.S. female participation lags behind that of other industrialised economies in part because of the cost of child care, which is subsidised elsewhere.

Rising wages lure workers, counter demographic shifts

Employers raised wages, offered employees more flexibility and improved benefits in recent years.

Average wage gains remain elevated this year and have recently surpassed inflation. And Americans are logging more hours of work from home than they did before the pandemic.

Employer recruitment efforts helped offset some broader demographic shifts, including an ageing population and rise in retirements.

The share of the population age 55 and over in the labor force climbed steadily from the mid-1990s through the 2008 financial crisis and remained elevated for more than a decade. The Covid-19 pandemic pushed many out of the workforce, and some older workers haven’t returned, particularly those over 65.

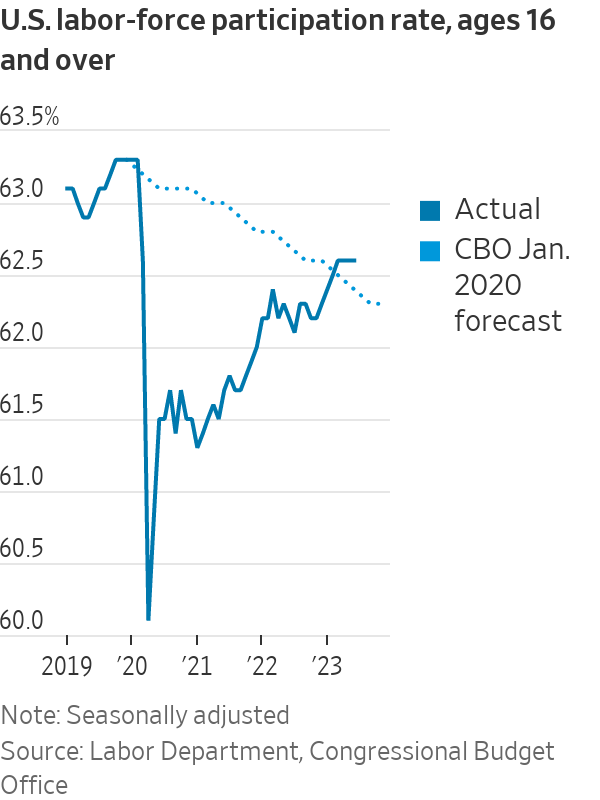

Much of the decline in the overall participation rate was anticipated as baby boomers aged out of the workforce, but the rise in prime-age workers meant the drop wasn’t as steep.

The Congressional Budget Office in January 2020, just before the pandemic hit, forecast the overall participation rate to deteriorate steadily through the 2020s, moving down to 62.4% in the second quarter of this year.

Instead, the rate was a couple of ticks higher in June at 62.6%, supported by prime-age workers.

“It seems like there is almost no cap on the supply of workers, only a speed limit on how fast we can bring them in,” Pollak said, referring to both rising prime-age participation and an influx of immigrants into the workforce.

Trends could turn if the economy cools

There are concerns that the Fed’s campaign to bring down inflation through higher interest rates will cause unemployment to rise too much and push some of the most vulnerable workers back to the sidelines.

The median forecast among Fed officials shows the unemployment rate rising to 4.1% by the end of this year and 4.5% next year from 3.6% in June, suggesting the economy will shed tens of thousands of jobs.

Labor-force participation tends to be cyclical, rising when the economy is strong and falling during downturns. A weaker labor market combined with structural barriers to employment could cap further gains.

With “current strength of labor demand set to fade, further progress from here will probably be more gradual,” Andrew Hunter, deputy chief U.S. economist at Capital Economics, said in a research note.

Copyright 2020, Dow Jones & Company, Inc. All Rights Reserved Worldwide. LEARN MORE

Copyright 2020, Dow Jones & Company, Inc. All Rights Reserved Worldwide. LEARN MORE

This stylish family home combines a classic palette and finishes with a flexible floorplan

Just 55 minutes from Sydney, make this your creative getaway located in the majestic Hawkesbury region.

Continued stagflation and cost of living pressures are causing couples to think twice about starting a family, new data has revealed, with long term impacts expected

Australia is in the midst of a ‘baby recession’ with preliminary estimates showing the number of births in 2023 fell by more than four percent to the lowest level since 2006, according to KPMG. The consultancy firm says this reflects the impact of cost-of-living pressures on the feasibility of younger Australians starting a family.

KPMG estimates that 289,100 babies were born in 2023. This compares to 300,684 babies in 2022 and 309,996 in 2021, according to the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS). KPMG urban economist Terry Rawnsley said weak economic growth often leads to a reduced number of births. In 2023, ABS data shows gross domestic product (GDP) fell to 1.5 percent. Despite the population growing by 2.5 percent in 2023, GDP on a per capita basis went into negative territory, down one percent over the 12 months.

“Birth rates provide insight into long-term population growth as well as the current confidence of Australian families,” said Mr Rawnsley. “We haven’t seen such a sharp drop in births in Australia since the period of economic stagflation in the 1970s, which coincided with the initial widespread adoption of the contraceptive pill.”

Mr Rawnsley said many Australian couples delayed starting a family while the pandemic played out in 2020. The number of births fell from 305,832 in 2019 to 294,369 in 2020. Then in 2021, strong employment and vast amounts of stimulus money, along with high household savings due to lockdowns, gave couples better financial means to have a baby. This led to a rebound in births.

However, the re-opening of the global economy in 2022 led to soaring inflation. By the start of 2023, the Australian consumer price index (CPI) had risen to its highest level since 1990 at 7.8 percent per annum. By that stage, the Reserve Bank had already commenced an aggressive rate-hiking strategy to fight inflation and had raised the cash rate every month between May and December 2022.

Five more rate hikes during 2023 put further pressure on couples with mortgages and put the brakes on family formation. “This combination of the pandemic and rapid economic changes explains the spike and subsequent sharp decline in birth rates we have observed over the past four years,” Mr Rawnsley said.

The impact of high costs of living on couples’ decision to have a baby is highlighted in births data for the capital cities. KPMG estimates there were 60,860 births in Sydney in 2023, down 8.6 percent from 2019. There were 56,270 births in Melbourne, down 7.3 percent. In Perth, there were 25,020 births, down 6 percent, while in Brisbane there were 30,250 births, down 4.3 percent. Canberra was the only capital city where there was no fall in the number of births in 2023 compared to 2019.

“CPI growth in Canberra has been slightly subdued compared to that in other major cities, and the economic outlook has remained strong,” Mr Rawnsley said. “This means families have not been hurting as much as those in other capital cities, and in turn, we’ve seen a stabilisation of births in the ACT.”

This stylish family home combines a classic palette and finishes with a flexible floorplan

Just 55 minutes from Sydney, make this your creative getaway located in the majestic Hawkesbury region.