America’s Hot Labour Market Fuels Job Growth in Unexpected Places

Payroll increase extends to building, home selling and auto making

The U.S. labor market is showing surprising pockets of strength as companies directly in the crosshairs of rising interest rates hold on to or add workers.

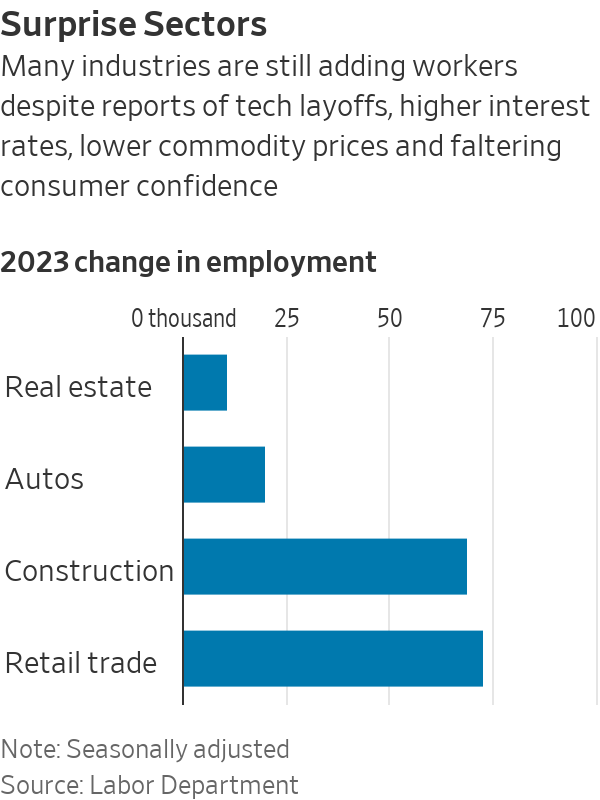

Builders, architects and engineers, real-estate agents, vehicle manufacturers and other businesses typically sensitive to higher borrowing costs have increased employment during the opening months of 2023.

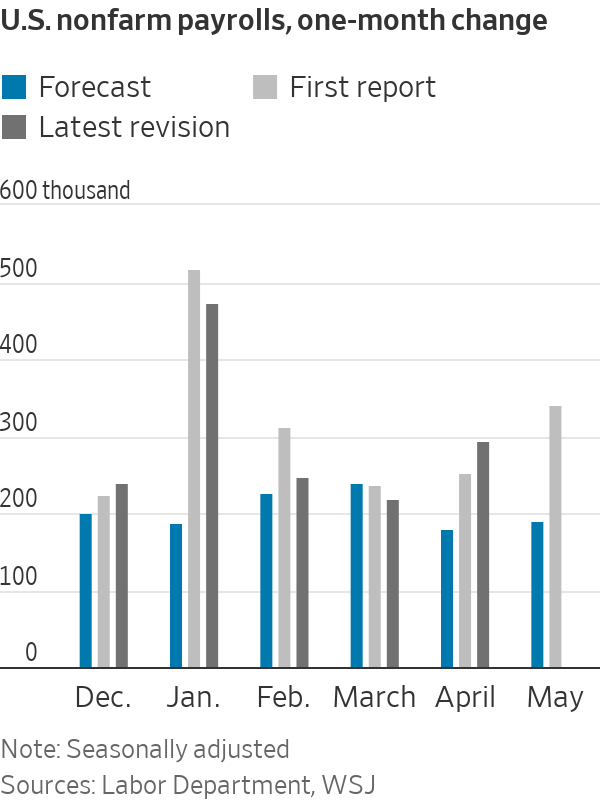

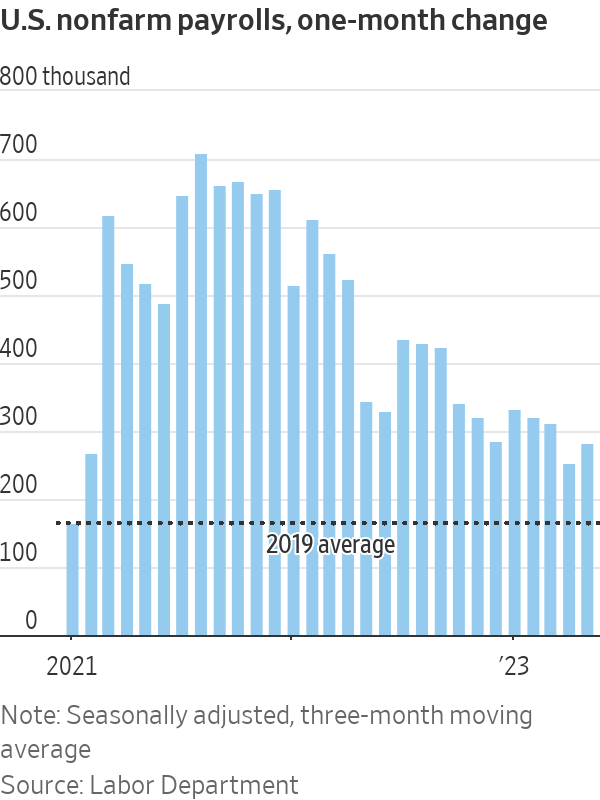

Those job gains, along with much larger increases in industries still trying to claw back workers lost during the pandemic, have added up to almost 1.6 million jobs in the first five months of 2023, outpacing economists’ forecasts.

The Labor Department will release June jobs figures on Friday.

“The labor market has continually surprised,” said Daniel Zhao, lead economist for the research team at Glassdoor, an online employment site.

Robust hiring defies theFederal Reserve

The strong job gains come despite companies and consumers facing higher borrowing costs.

The Federal Reserve raised interest rates to a 16-year high in 2023. And it is expected to increase them further later this year as part of a campaign to slow the economy, cool the labor market and tamp down inflation that is running too hot.

Some industries are defying the Fed’s efforts.

Construction employment has been one of the biggest surprises in recent months. In the past, builders have been hit especially hard when interest rates rose.

But employment in residential construction has merely levelled off in 2023, while industrial and infrastructure businesses gallop ahead.

Projects related to electric-vehicle batteries and semiconductors are driving much of the growth, spurred in part by the Chips and Science Act of 2022, which set aside $52.7 billion for financial assistance for the construction and expansion of semiconductor manufacturing facilities and other programs.

“Many of these were announced or broke ground before the Chips Act, but that added fuel to the bonfire,” said Kenneth Simonson, chief economist at Associated General Contractors of America.

Architectural and engineering firms have also added workers. The real-estate industry hasn’t shed any jobs this year despite a slowdown in single-family home sales.

American factories also often get caught in the Fed’s crosshairs when costs go up for auto loans and other personal loans. But auto and parts manufacturers have added almost 20,000 workers so far in 2023, helping to offset losses at makers of furniture, plastics and paper products.

According to Commerce Department data, car sales are still below pre pandemic levels, held back by limited supplies and high prices. But figures from the Fed show factories are trying to catch up. Auto and light-truck assemblies were above an annual pace of 11 million in April and May, the first time that number has been topped in back-to-back months since 2018.

Some employers stabilise, others heat up

The story is similar in other corners of the economy. Home-improvement and furniture stores have shed workers, for example, but department stores and warehouse clubs have added them. The final result: Overall retail employment has grown slightly so far this year.

The financial sector has also posted growth despite banking sector turmoil, with gains at insurers, brokers and financial advisers outpacing losses in banking.

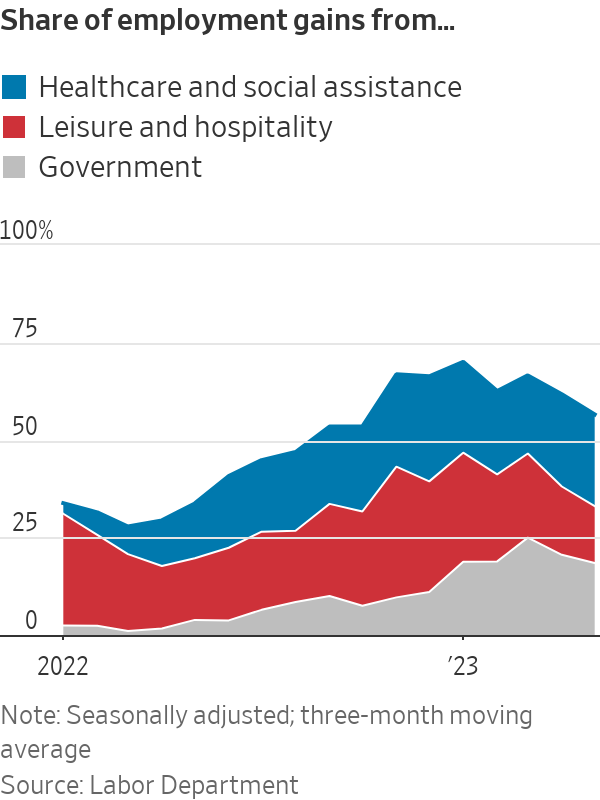

Other sectors aren’t merely holding up—they are rapidly hiring. Government, leisure and hospitality and healthcare account for about 60% of all employment gains so far in 2023. The first two categories are still playing Covid-19 catch-up: Employment at restaurants, hotels, schools and in other municipal services are still below pre pandemic levels.

The picture isn’t entirely rosy.

Tech layoffs are well documented. Some economists worry that residential construction employment could be headed for a fall as a big run-up in apartment projects leads to an oversupply of units and signs of falling rents.

The number of hours people are spending on the job is declining, a possible sign that employers have less work for them. Wage growth remains strong but has eased, suggesting that demand for workers is cooling. And job growth has become more concentrated in fewer industries, possibly indicating that the breadth of the economic expansion is also narrowing.

“There are signals on the periphery that the labor market is slowing,” said Brett Ryan, senior U.S. economist at Deutsche Bank.

Copyright 2020, Dow Jones & Company, Inc. All Rights Reserved Worldwide. LEARN MORE

Copyright 2020, Dow Jones & Company, Inc. All Rights Reserved Worldwide. LEARN MORE

This stylish family home combines a classic palette and finishes with a flexible floorplan

Just 55 minutes from Sydney, make this your creative getaway located in the majestic Hawkesbury region.

Impact investing is becoming more mainstream as larger, institutional asset owners drive more money into the sector, according to the nonprofit Global Impact Investing Network in New York.

In the GIIN’s State of the Market 2024 report, published late last month, researchers found that assets allocated to impact-investing strategies by repeat survey responders grew by a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of 14% over the last five years.

These 71 responders to both the 2019 and 2024 surveys saw their total impact assets under management grow to US$249 billion this year from US$129 billion five years ago.

Medium- and large-size investors were largely responsible for the strong impact returns: Medium-size investors posted a median CAGR of 11% a year over the five-year period, and large-size investors posted a median CAGR of 14% a year.

Interestingly, the CAGR of assets held by small investors dropped by a median of 14% a year.

“When we drill down behind the compound annual growth of the assets that are being allocated to impact investing, it’s largely those larger investors that are actually driving it,” says Dean Hand, the GIIN’s chief research officer.

Overall, the GIIN surveyed 305 investors with a combined US$490 billion under management from 39 countries. Nearly three-quarters of the responders were investment managers, while 10% were foundations, and 3% were family offices. Development finance institutions, institutional asset owners, and companies represented most of the rest.

The majority of impact strategies are executed through private-equity, but public debt and equity have been the fastest-growing asset classes over the past five years, the report said. Public debt is growing at a CAGR of 32%, and public equity is growing at a CAGR of 19%. That compares to a CAGR of 17% for private equity and 7% for private debt.

According to the GIIN, the rise in public impact assets is being driven by larger investors, likely institutions.

Private equity has traditionally served as an ideal way to execute impact strategies, as it allows investors to select vehicles specifically designed to create a positive social or environmental impact by, for example, providing loans to smallholder farmers in Africa or by supporting fledging renewable energy technologies.

Future Returns: Preqin expects managers to rely on family offices, private banks, and individual investors for growth in the next six years

But today, institutional investors are looking across their portfolios—encompassing both private and public assets—to achieve their impact goals.

“Institutional asset owners are saying, ‘In the interests of our ultimate beneficiaries, we probably need to start driving these strategies across our assets,’” Hand says. Instead of carving out a dedicated impact strategy, these investors are taking “a holistic portfolio approach.”

An institutional manager may want to address issues such as climate change, healthcare costs, and local economic growth so it can support a better quality of life for its beneficiaries.

To achieve these goals, the manager could invest across a range of private debt, private equity, and real estate.

But the public markets offer opportunities, too. Using public debt, a manager could, for example, invest in green bonds, regional bank bonds, or healthcare social bonds. In public equity, it could invest in green-power storage technologies, minority-focused real-estate trusts, and in pharmaceutical and medical-care company stocks with the aim of influencing them to lower the costs of care, according to an example the GIIN lays out in a separate report on institutional strategies.

Influencing companies to act in the best interests of society and the environment is increasingly being done through such shareholder advocacy, either directly through ownership in individual stocks or through fund vehicles.

“They’re trying to move their portfolio companies to actually solving some of the challenges that exist,” Hand says.

Although the rate of growth in public strategies for impact is brisk, among survey respondents investments in public debt totaled only 12% of assets and just 7% in public equity. Private equity, however, grabs 43% of these investors’ assets.

Within private equity, Hand also discerns more evidence of maturity in the impact sector. That’s because more impact-oriented asset owners invest in mature and growth-stage companies, which are favored by larger asset owners that have more substantial assets to put to work.

The GIIN State of the Market report also found that impact asset owners are largely happy with both the financial performance and impact results of their holdings.

About three-quarters of those surveyed were seeking risk-adjusted, market-rate returns, although foundations were an exception as 68% sought below-market returns, the report said. Overall, 86% reported their investments were performing in line or above their expectations—even when their targets were not met—and 90% said the same for their impact returns.

Private-equity posted the strongest results, returning 17% on average, although that was less than the 19% targeted return. By contrast, public equity returned 11%, above a 10% target.

The fact some asset classes over performed and others underperformed, shows that “normal economic forces are at play in the market,” Hand says.

Although investors are satisfied with their impact performance, they are still dealing with a fragmented approach for measuring it, the report said. “Despite this, over two-thirds of investors are incorporating impact criteria into their investment governance documents, signalling a significant shift toward formalising impact considerations in decision-making processes,” it said.

Also, more investors are getting third-party verification of their results, which strengthens their accountability in the market.

“The satisfaction with performance is nice to see,” Hand says. “But we do need to see more about what’s happening in terms of investors being able to actually track both the impact performance in real terms as well as the financial performance in real terms.”

This stylish family home combines a classic palette and finishes with a flexible floorplan

Just 55 minutes from Sydney, make this your creative getaway located in the majestic Hawkesbury region.