China’s Inflation Problem? It Has None

Falling prices at the factory gate and subdued increases in the costs of consumer goods contrast with searing inflation in many countries

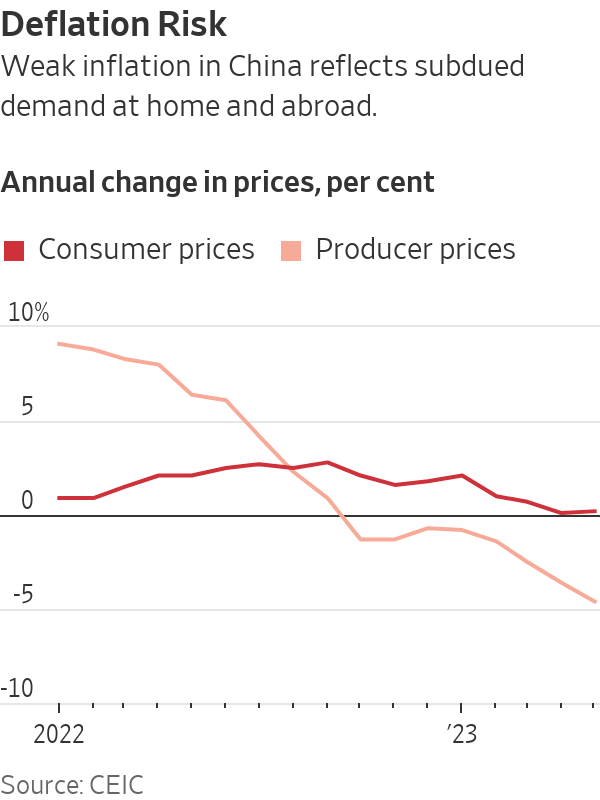

SINGAPORE—As Western central banks continue to jack up interest rates in an effort to douse stubbornly high inflation, China faces a growing risk of the opposite problem—deflation.

Prices charged by Chinese factories tumbled in May at their steepest annual pace in seven years, while consumer prices barely budged, fresh signs of the challenges faced by the world’s second-largest economy both at home and abroad.

Economists say the absence of inflationary pressure means China could experience a spell of deflation—a widespread fall in prices—if the economy doesn’t pick up soon.

Persistent deflation tends to throttle growth and can be difficult to escape. While a prolonged period of falling prices probably isn’t in the cards, Chinese policy makers will nonetheless need to do more to stave off that risk and get the economy motoring again, economists say, perhaps by trimming interest rates, weakening the currency or offering cash or other spending inducements to households and businesses.

Ting Lu, chief China economist at Nomura in Hong Kong, said in a note to clients Friday that he expects local banks to cut key lending rates as soon as next week.

In remarks made at a meeting Wednesday and published by China’s central bank after the release of monthly inflation data Friday, central-bank Gov. Yi Gang said he expects consumer-price inflation to edge up in the second half of the year and exceed 1% in December. He said the People’s Bank of China would use its tools to support the economy and promote employment.

Falling prices in China aren’t necessarily bad news for the global economy, as lower costs to import Chinese goods should help bring down inflation rates that for many economies are still uncomfortably high.

“In a sense, China is already exporting deflation to the world,” said Carlos Casanova, senior Asia economist at Union Bancaire Privée in Hong Kong. That could help ease the pressure on the U.S. Federal Reserve and other central banks that are battling to bring down inflation, he said.

China’s producer prices—what companies charge at the factory gate—fell 4.6% from a year earlier in May, the weakest reading since early 2016 and the eighth straight month of declines.

Consumer prices rose just 0.2%, China’s National Bureau of Statistics said Friday, slightly higher than the 0.1% annual gain recorded in April but still well below the 3% ceiling for annual inflation set by the government and central bank.

In the U.S., consumer-price inflation in April slowed to a 4.9% annual rate, but that was still more than double the Federal Reserve’s 2% goal. In the 20 nations that use the euro, annual inflation was 6.1% in May.

After soaring last year in the wake of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, prices of crude oil, food and some other commodities have pulled back, partly leading to China’s subdued inflation.

But also behind China’s predicament, which stands in contrast to the experience of most other economies as they emerged from the Covid-19 pandemic, is a shortfall in spending both domestically and from overseas.

Chinese factories are cutting prices because foreigners aren’t buying their goods with the same gusto as before central banks started ratcheting up borrowing costs. A hoped for consumer spending binge that was supposed to propel growth in China hasn’t materialised. Real estate is in the doldrums, crushing investment.

Western policy makers and economists are exploring whether fat corporate profit margins are stoking inflation in their economies. In China, industrial profits are sinking.

The inflation data adds to a string of disappointing signals on the strength of China’s recovery, which had been expected to power global growth this year after Beijing ditched its draconian Covid controls at the close of 2022.

Chinese exports fell in May from a year earlier, the first annual decline in overseas shipments in three months. Business surveys showed factory activity shrank in May and services-sector activity softened. More than a fifth of young people are unemployed.

Still, most economists think China will meet or exceed the government’s goal of growing the economy by 5% or more this year, given the weak base of comparison with 2022, when sporadic lockdowns in major cities hammered the economy.

Zichun Huang, China economist at Capital Economics, said she doesn’t think China will experience broad deflation and expects consumer price growth to pick up in the coming months thanks to support from policy makers and an improving labor market.

—Grace Zhu in Beijing contributed to this article.

Copyright 2020, Dow Jones & Company, Inc. All Rights Reserved Worldwide. LEARN MORE

Copyright 2020, Dow Jones & Company, Inc. All Rights Reserved Worldwide. LEARN MORE

This stylish family home combines a classic palette and finishes with a flexible floorplan

Just 55 minutes from Sydney, make this your creative getaway located in the majestic Hawkesbury region.

Continued stagflation and cost of living pressures are causing couples to think twice about starting a family, new data has revealed, with long term impacts expected

Australia is in the midst of a ‘baby recession’ with preliminary estimates showing the number of births in 2023 fell by more than four percent to the lowest level since 2006, according to KPMG. The consultancy firm says this reflects the impact of cost-of-living pressures on the feasibility of younger Australians starting a family.

KPMG estimates that 289,100 babies were born in 2023. This compares to 300,684 babies in 2022 and 309,996 in 2021, according to the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS). KPMG urban economist Terry Rawnsley said weak economic growth often leads to a reduced number of births. In 2023, ABS data shows gross domestic product (GDP) fell to 1.5 percent. Despite the population growing by 2.5 percent in 2023, GDP on a per capita basis went into negative territory, down one percent over the 12 months.

“Birth rates provide insight into long-term population growth as well as the current confidence of Australian families,” said Mr Rawnsley. “We haven’t seen such a sharp drop in births in Australia since the period of economic stagflation in the 1970s, which coincided with the initial widespread adoption of the contraceptive pill.”

Mr Rawnsley said many Australian couples delayed starting a family while the pandemic played out in 2020. The number of births fell from 305,832 in 2019 to 294,369 in 2020. Then in 2021, strong employment and vast amounts of stimulus money, along with high household savings due to lockdowns, gave couples better financial means to have a baby. This led to a rebound in births.

However, the re-opening of the global economy in 2022 led to soaring inflation. By the start of 2023, the Australian consumer price index (CPI) had risen to its highest level since 1990 at 7.8 percent per annum. By that stage, the Reserve Bank had already commenced an aggressive rate-hiking strategy to fight inflation and had raised the cash rate every month between May and December 2022.

Five more rate hikes during 2023 put further pressure on couples with mortgages and put the brakes on family formation. “This combination of the pandemic and rapid economic changes explains the spike and subsequent sharp decline in birth rates we have observed over the past four years,” Mr Rawnsley said.

The impact of high costs of living on couples’ decision to have a baby is highlighted in births data for the capital cities. KPMG estimates there were 60,860 births in Sydney in 2023, down 8.6 percent from 2019. There were 56,270 births in Melbourne, down 7.3 percent. In Perth, there were 25,020 births, down 6 percent, while in Brisbane there were 30,250 births, down 4.3 percent. Canberra was the only capital city where there was no fall in the number of births in 2023 compared to 2019.

“CPI growth in Canberra has been slightly subdued compared to that in other major cities, and the economic outlook has remained strong,” Mr Rawnsley said. “This means families have not been hurting as much as those in other capital cities, and in turn, we’ve seen a stabilisation of births in the ACT.”

This stylish family home combines a classic palette and finishes with a flexible floorplan

Just 55 minutes from Sydney, make this your creative getaway located in the majestic Hawkesbury region.