Crypto’s Onetime Fans Are Calling It Quits After FTX Collapse

Debacle is last straw for many who embraced crypto during pandemic

Buying crypto was so much fun when it was going up. Now, many onetime fans are getting out.

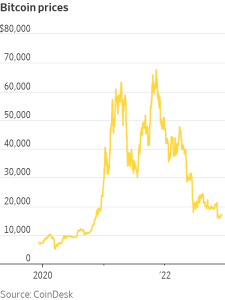

This year has brought crisis after crisis, raising questions about the industry’s long-term prospects. Two major lenders, Voyager Digital and Celsius Network, filed for bankruptcy this summer. The price of bitcoin has plunged some 75% from its peak late last year. For some traders, the recent collapse of the crypto exchange FTX—which is dragging down other firms—was the last straw.

Crypto fund asset managers saw investors withdraw almost $20 billion in November, or nearly 15% of total assets under management, according to the research firm CryptoCompare. That brought the fund managers’ collective AUM to its lowest point in nearly two years. By contrast, many small-time investors continue to stay in the relatively boring stock market, despite losses there as well.

Dennis Drent, a former executive at a pet-insurance company, said he waded into the crypto market last December, when the world felt very different. He was growing anxious that the stock market’s record run would soon sputter and was frustrated by how little his bond investments were generating.

Around that time, he caught an appearance by a bitcoin proponent, Michael Saylor, with Fox News’s Tucker Carlson.

“He had me convinced that you can’t lose,” said Mr. Drent, who lives in Southern California.

A few weeks later, he poured about $25,000 into Grayscale Bitcoin Trust. He even had a nod from his financial adviser, he said.

It didn’t work. Mr. Drent cashed out in May, taking about a 50% loss. By then, crypto prices were falling fast. But so were stocks and bonds, an unusual coupling that reflected broad uncertainty.

Mr. Drent said he should have known to avoid a market that was so lightly regulated and that he didn’t fully understand: “I wasn’t cautious enough.”

Mr. Saylor didn’t respond to a request for comment.

Crypto use exploded over the past few years and so did crypto prices, with bitcoin soaring from roughly $9,000 in early March 2020 to about $68,000 at its peak in November 2021.

Rookie traders stuck at home during pandemic lockdowns downloaded apps that made it easy to buy crypto with a few taps on their phones. Some embraced active trading, darting in and out of different cryptocurrencies. Others thought they were taking a safer route by parking their crypto holdings at companies that offered eye-popping yields in return.

The share of U.S. households that have ever transferred funds into a crypto-related account jumped to 13% as of June 2022, up from 3% before 2020, according to data from the JPMorgan Chase Institute. It estimates that many new investors flocked to crypto for the first time last year, with activity among new users peaking around the time bitcoin prices did in November. Since then, activity has tumbled.

While crypto prices soared, financial-services companies rolled out new products and services to allow everyday investors to add crypto to their nest eggs. Some of that enthusiasm has waned.

“New customer additions have slowed…because the trust of the industry has been damaged,” said Chris Kline, co-founder of Bitcoin IRA, which allows investors to trade crypto through retirement accounts.

Making matters worse, many people followed the herd and bought crypto only when prices rose.

JPMorgan estimates that many investors who transferred money to crypto accounts did so when prices were much higher than they are now. That means many investors are likely sitting on losses.

Of course, plenty of crypto traders say they are holding on or trying to buy the dip in cryptocurrencies. Some are doing so because they believe in crypto as a conduit to change global finance. Others just don’t need the money soon.

Stephen Jones, 28 years old, said he started buying cryptocurrencies when he was in college. Mr. Jones notched some wins but started having doubts over the past year, so he sold out of some positions. Getting married in June pushed him to take another closer look at his finances, he said.

Finally, he decided to cash out his remaining holdings in October. When he saw FTX collapse shortly afterward, he was relieved that he had already dumped his crypto.

FTX “definitely opened my eyes a little bit,” said Mr. Jones, who works in finance and is based in Houston. “I’m not really seeing as much value-added activity as was initially promised.”

Nick Torrico, 26, had about $10,000 in mainly bitcoin, Ethereum and VeChain at Voyager when it filed for bankruptcy in July, and he doesn’t know if he will see all of that money again.

After diving into cryptocurrencies a few years ago, he has pulled back on some of his trading, especially in smaller coins.

Mr. Torrico said he is glad that he has diversified his holdings and didn’t pour all of his money into crypto. He is holding more in cash in his investment account. He has made some stock trades with borrowed money and could face margin calls if shares of some of his companies fall farther.

Still, Mr. Torrico, who works in finance, said he remains optimistic about blockchain technology and expects more regulation of crypto, which he thinks will help the industry. He still holds bitcoin and ether, the two biggest cryptocurrencies, and plans to keep buying regularly.

“A lot of bad actors have been exposed,” Mr. Torrico said. “My biggest lesson is to be patient and not try to make fast money.”

—David Benoit contributed to this article.

Copyright 2020, Dow Jones & Company, Inc. All Rights Reserved Worldwide. LEARN MORE

Copyright 2020, Dow Jones & Company, Inc. All Rights Reserved Worldwide. LEARN MORE

This stylish family home combines a classic palette and finishes with a flexible floorplan

Just 55 minutes from Sydney, make this your creative getaway located in the majestic Hawkesbury region.

Continued stagflation and cost of living pressures are causing couples to think twice about starting a family, new data has revealed, with long term impacts expected

Australia is in the midst of a ‘baby recession’ with preliminary estimates showing the number of births in 2023 fell by more than four percent to the lowest level since 2006, according to KPMG. The consultancy firm says this reflects the impact of cost-of-living pressures on the feasibility of younger Australians starting a family.

KPMG estimates that 289,100 babies were born in 2023. This compares to 300,684 babies in 2022 and 309,996 in 2021, according to the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS). KPMG urban economist Terry Rawnsley said weak economic growth often leads to a reduced number of births. In 2023, ABS data shows gross domestic product (GDP) fell to 1.5 percent. Despite the population growing by 2.5 percent in 2023, GDP on a per capita basis went into negative territory, down one percent over the 12 months.

“Birth rates provide insight into long-term population growth as well as the current confidence of Australian families,” said Mr Rawnsley. “We haven’t seen such a sharp drop in births in Australia since the period of economic stagflation in the 1970s, which coincided with the initial widespread adoption of the contraceptive pill.”

Mr Rawnsley said many Australian couples delayed starting a family while the pandemic played out in 2020. The number of births fell from 305,832 in 2019 to 294,369 in 2020. Then in 2021, strong employment and vast amounts of stimulus money, along with high household savings due to lockdowns, gave couples better financial means to have a baby. This led to a rebound in births.

However, the re-opening of the global economy in 2022 led to soaring inflation. By the start of 2023, the Australian consumer price index (CPI) had risen to its highest level since 1990 at 7.8 percent per annum. By that stage, the Reserve Bank had already commenced an aggressive rate-hiking strategy to fight inflation and had raised the cash rate every month between May and December 2022.

Five more rate hikes during 2023 put further pressure on couples with mortgages and put the brakes on family formation. “This combination of the pandemic and rapid economic changes explains the spike and subsequent sharp decline in birth rates we have observed over the past four years,” Mr Rawnsley said.

The impact of high costs of living on couples’ decision to have a baby is highlighted in births data for the capital cities. KPMG estimates there were 60,860 births in Sydney in 2023, down 8.6 percent from 2019. There were 56,270 births in Melbourne, down 7.3 percent. In Perth, there were 25,020 births, down 6 percent, while in Brisbane there were 30,250 births, down 4.3 percent. Canberra was the only capital city where there was no fall in the number of births in 2023 compared to 2019.

“CPI growth in Canberra has been slightly subdued compared to that in other major cities, and the economic outlook has remained strong,” Mr Rawnsley said. “This means families have not been hurting as much as those in other capital cities, and in turn, we’ve seen a stabilisation of births in the ACT.”

This stylish family home combines a classic palette and finishes with a flexible floorplan

Just 55 minutes from Sydney, make this your creative getaway located in the majestic Hawkesbury region.