Disney Goes All In on Sports Betting

After years of internal debate, the entertainment giant did a deal with a gambling company and will launch an ESPN betting app next month. Can it draw a bigger sports crowd without alienating Mickey’s fans?

In early 2019, an analyst asked Disney Chief Executive Bob Iger if sports betting could coexist with the House of Mouse’s brand. He said he didn’t see the company facilitating gambling in any way.

Just four years later, the world’s most beloved name in family entertainment is going all-in on sports betting.

In August, the company struck a 10-year deal with sports-betting company Penn Entertainment to bring gambling to Disney’s ESPN sports network. Sports fans will be able to wager on games on their phones through a new app called ESPN Bet that accepts bets through Penn’s sportsbook.

The idea of gambling under the same roof as Disney has roiled some company executives and employees who feel it will damage the brand that is synonymous with princesses and talking cartoon ducks. In the last year, at least one large investor warned Disney that it might have to sell some of its Disney stake if the company embraced betting.

But for ESPN President Jimmy Pitaro and Iger, who saw his two adult sons glued to gambling apps on their smartphones, the chance to engage a younger male audience, and the money, were eventually too good to pass up. Penn will pay Disney $1.5 billion in cash while ESPN will receive warrants worth about $500 million to purchase shares in the gambling company. Penn will operate the app and Disney will help market it.

This is how sports in America works. Fans watch and they bet—particularly young men between the ages of 18 and 34—often making multiple complicated bets during a live sporting event. They can wager on how many 3-pointers a basketball player will sink or who will catch the final fly ball in a baseball game. It is huge on college campuses.

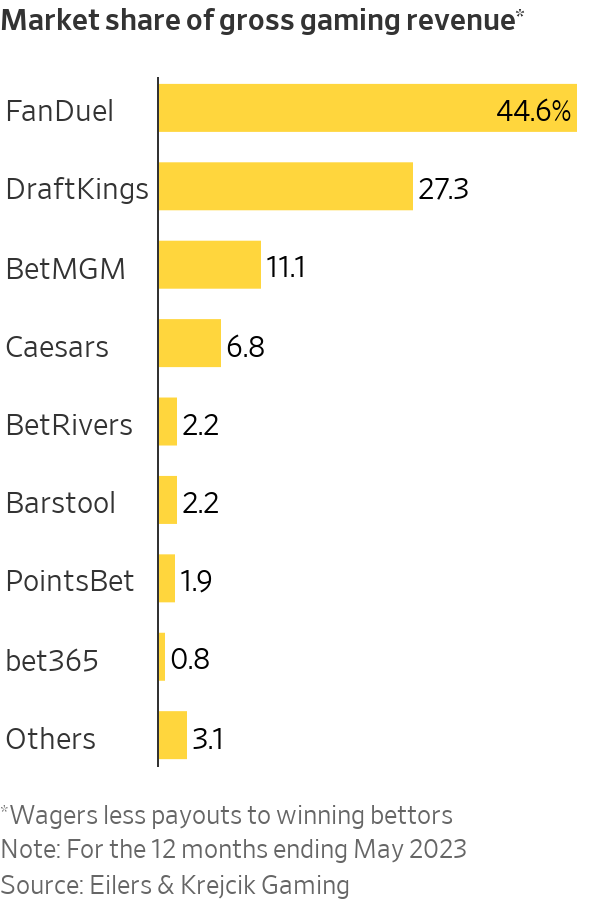

Wagering on games ballooned after a 2018 Supreme Court ruling cleared the way for states to adopt it. It is legal in 38 states and the District of Columbia. Last year, online sports gambling generated $7.6 billion in revenue—the amount companies received after paying out winning bets. Next year, revenue is expected to grow to $11.8 billion, according to Eilers & Krejcik Gaming, an industry consulting firm.

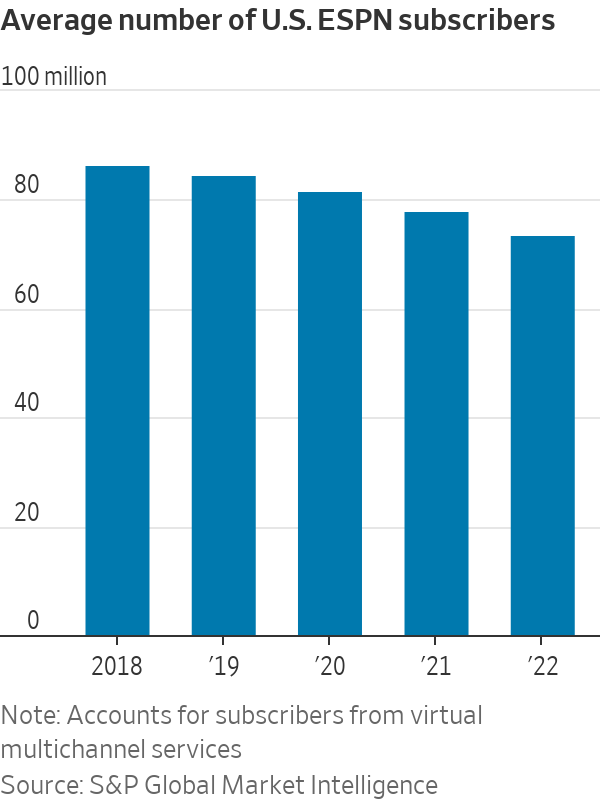

ESPN, like more traditional TV networks, is struggling with the decline in cable TV subscribers and the rising cost of sports-broadcasting rights. Sports leagues and legions of startups have embraced gambling, while large media companies have homed in on betting as one of the best ways to expand.

But Disney employees, more than most other workers, feel that their company stands for a set of wholesome ideals—something more than making money.

In mid-2022, Jenny Cohen, a Disney veteran who had been promoted to head of corporate social responsibility a year earlier, raised concerns about a potential foray into sports betting to top executives at Disney’s Burbank, Calif., headquarters and leaders at ESPN, urging them to reconsider their plan to strike a deal with a sports-betting operator.

She told her colleagues, and Disney’s CEO at the time, Bob Chapek, that sports betting would tarnish the Disney brand, according to people familiar with the discussions. Consumers could start associating Disney with gambling addiction, she argued. As this discussion brewed, Disney was already managing a crisis with many employees who felt their employer didn’t take enough of a stand against a Florida bill that prohibits instruction on sexual orientation or gender identity for young students, known by its opponents as the “Don’t Say Gay” legislation.

Around the same time, BlackRock, the investment giant which uses socially-conscious environmental, social and governance—or ESG—criteria to guide some of its investing decisions, contacted Disney’s investor relations staff. It warned Disney that if the company did a deal with a sportsbook, ESG rules may require some of its European funds to reduce their Disney stakes, people familiar with the matter said.

Disney is also contending with a fresh push by activist investor Nelson Peltz’s Trian Fund Management to secure multiple board seats, The Journal reported this week. Trian thinks Disney’s stock is undervalued and that Disney needs a board that is more focused and accountable. It is unclear what other changes the hedge fund plans to seek. Peltz and Trian haven’t publicly taken a position on ESPN and gambling.

There are Disney fans, Disney+ subscribers and theme park visitors that likely have no idea that ESPN is part of Disney, but internally, Disney’s businesses are perceived as interconnected parts of one overarching corporate brand: a place where dreams come true. The ESPN+ streaming service is offered as part of Disney’s streaming bundle, and ESPN promotes shows from other Disney-owned networks during its broadcasts, and vice versa. This week, for example, ABC late-night host Jimmy Kimmel appeared on ESPN2’s football show the “Manningcast.”

“My job is to protect the brand at all costs,” said Pitaro, in an interview. “I am the custodian of the ESPN brand, and we needed to make sure that whoever we went with on this journey was someone that we could trust.”

Disney first began flirting with sports betting in March 2019, when it completed its $71.3 billion acquisition of Fox’s major entertainment assets, which included a 6% stake in sports betting company DraftKings.

At the time, some of Iger’s top lieutenants urged him to take a bigger ownership stake in the gambling company, but Iger resisted, arguing that betting wasn’t on-brand for Disney.

Without his blessing, sports-betting discussions stalled until Iger stepped down as CEO in February of 2020, and the board named his veteran head of parks, Chapek, to replace him.

Chapek had a much different view of gambling. He told associates that he was “not that precious about the Disney brand,” compared with his predecessor when it came to sports betting.

He began exploring a potential partnership with a sportsbook, and Disney started up talks with DraftKings, which now has more than 30% share of the sports-betting market. At the time, DraftKings had a marketing arrangement with ESPN, by which it would link ESPN.com readers to make online bets through DraftKings.

Despite Cohen’s objections, Disney signalled that it was seeking a new deal worth around $3 billion over a decade, and Chapek and Pitaro gave news interviews, saying that ESPN customers wanted a “seamless” betting option as part of the sports-viewing experience. ESPN had already embraced sports betting within its programming, including in its “Daily Wager” show, which analyses odds for sports matchups.

Pitaro intensified his matchmaking efforts with DraftKings, but from the outset, the two companies were far apart. Disney asked for tens of millions of dollars a year more than DraftKings was willing to pay, according to a person familiar with the matter.

Eventually, DraftKings offered around $100 million a year for ESPN to use its sportsbook, but DraftKings wanted its brand included on any app or marketing as part of the deal. That was a nonstarter for Pitaro. He wanted solo ESPN branding.

His team began negotiating with Rush Street Interactive, a smaller, Chicago-based gambling company. RSI offered ESPN more than $100 million a year, but a deal never came together.

Pitaro felt pressure to secure ESPN’s future, particularly among young male fans who increasingly expect betting to be a seamlessly-integrated part of the sports-watching experience. By this time, Iger had returned to Disney as its CEO after the board ousted Chapek in November of last year, and the company was hard at work on plans to remake ESPN as a streaming-focused platform. Iger had told interviewers that he had seen the writing on the wall for the traditional TV business, which was showing signs of being on its deathbed.

Overall, Disney was struggling. Its foundering share price had drawn attacks from activist investors including both Peltz and Dan Loeb’s Third Point, its streaming business was bleeding cash and its whole traditional television business, more than just ESPN, was suffering as more people dropped their cable TV subscriptions in favour of streaming. Disney is currently exploring potential strategic partners for ESPN and has had talks with major sports leagues about it.

Iger quickly set about trimming fat, announcing $5.5 billion in budget cuts and the elimination of 7,000 positions, around 3% of Disney’s total global workforce.

Soon, Iger warmed up to sports betting. His adult sons’ use of sports-betting apps opened his eyes to its popularity with a younger audience, he told associates. He said that it is “inevitable” that sports-watching and sports-betting will go hand-in-hand, and he blessed Pitaro’s efforts to find Disney a partner. Getting involved with gambling was the only way to ensure that ESPN is able to continue to attract younger audiences, he reasoned.

Along came Penn, the Wyomissing, Pa.-based casino operator turned sports-betting company that also needed a makeover after it got into regulatory and reputational trouble over its ownership of sports-media company Barstool Sports, founded by Dave Portnoy. Several women have accused Portnoy of sexual misconduct—allegations he has denied.

Penn runs casinos and racetracks in smaller regional markets like Lake Charles, La., Biloxi, Miss., and York, Pa., and its CEO Jay Snowden wanted to remake the company into a digital gambling powerhouse.

Snowden first met Pitaro in his office for about a 90-minute meeting earlier this year. Pitaro left thinking Snowden was “a straight shooter” who knew what he was doing, the ESPN executive said.

Pitaro quickly deployed teams working on ESPN’s sports-betting, tech, strategy and marketing into parallel talks with Penn to flesh out what a potential partnership could look like. He said Penn’s technology, including the functionality and design of the app, stood out. In addition, Disney views Penn’s tiny market share as an advantage because ESPN can have more control over branding the app and not have to share the spotlight with a better-established player, according to people familiar with Disney’s stance.

There was a key requirement to move forward with a Disney deal. Penn had to dump Barstool.

When Penn began acquiring Barstool in a series of transactions starting in 2020, the gambling company hoped it would help it build a young customer base. Barstool runs an extensive sports-content operation that has drawn criticism for sexism and some of its employees’ crude behaviour. Gambling regulators ultimately fined Penn for violating rules about marketing to people under the age of 21 and scrutinised advertisements that appeared to promise financial success. Barstool said it was being sarcastic.

Pitaro informed Iger of the talks in an early June meeting, and the CEO liked the idea of a partnership with Penn. Pitaro had long held out hope that Disney could fashion a deal with DraftKings, a market-leading online gambling company that was seen by some inside Disney as a natural fit, but the negotiations had become bogged down.

Pitaro suggested that they end talks with DraftKings. Iger, who felt that the negotiations had gone on too long and DraftKings’ demands weren’t reasonable, agreed. Besides, Penn was offering a better price. It was time to move on.

In June, Pitaro presented the Penn deal to Disney’s board at a meeting in Anaheim, Calif., and in early August, the day before Disney was set to announce third-quarter financial results, Disney announced the $2 billion deal.

Penn needed to rebrand the Barstool Sportsbook app into ESPN Bet under the new deal. To quickly make room for Disney, the company sold Barstool back to Portnoy for $1, just six months after fully acquiring the company. Penn kept the database of 1.5 million online betting customers it has accrued, which the company aims to retain under the ESPN name.

ESPN and Penn have the option to walk away from the partnership in three years if the venture hasn’t captured a minimum market share target. Snowden declined to say the exact target, but said it was around 10%.

“There’s only one ESPN,” Snowden said. “If we were going to make a pivot, there was really one option to do that, and that was with what is the only name that is truly synonymous with sports in the United States.”

ESPN sports programming won’t be pushed into the betting app when it launches in November so as not to slow down the betting experience, Snowden said. Instead, the goal is for ESPN viewers and readers to easily switch back and forth between sports and the betting app.

Pitaro said that many on-air stars are eager to get involved with ESPN Bet, and the company plans to announce an expanded talent lineup to host and promote its gambling-related products and shows. ESPN forged a partnership with former NFL punter and foul-mouthed YouTube star Pat McAfee, who is known for hosting broadcasts in sleeveless T-shirts and making occasional off-colour jokes. He will promote ESPN Bet to his audience.

ESPN is also considering alternative broadcasts of games focused on betting, similar to the popular version of Monday Night Football hosted by former NFL stars and brothers Eli and Peyton Manning that airs on ESPN2 and ESPN+, and plans to promote betting to its growing fantasy-sports audience. Pitaro said its fantasy platform is expected to reach more than 12 million users this year, a 10% increase from the previous year.

“Getting into sports betting is a perceived business necessity for ESPN,” said John Kosner, a former ESPN executive who now runs Kosner Media. “I think this decision has to do more with ESPN’s manifest destiny than Disney’s position on branding.”

Copyright 2020, Dow Jones & Company, Inc. All Rights Reserved Worldwide. LEARN MORE

Copyright 2020, Dow Jones & Company, Inc. All Rights Reserved Worldwide. LEARN MORE

This stylish family home combines a classic palette and finishes with a flexible floorplan

Just 55 minutes from Sydney, make this your creative getaway located in the majestic Hawkesbury region.

Continued stagflation and cost of living pressures are causing couples to think twice about starting a family, new data has revealed, with long term impacts expected

Australia is in the midst of a ‘baby recession’ with preliminary estimates showing the number of births in 2023 fell by more than four percent to the lowest level since 2006, according to KPMG. The consultancy firm says this reflects the impact of cost-of-living pressures on the feasibility of younger Australians starting a family.

KPMG estimates that 289,100 babies were born in 2023. This compares to 300,684 babies in 2022 and 309,996 in 2021, according to the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS). KPMG urban economist Terry Rawnsley said weak economic growth often leads to a reduced number of births. In 2023, ABS data shows gross domestic product (GDP) fell to 1.5 percent. Despite the population growing by 2.5 percent in 2023, GDP on a per capita basis went into negative territory, down one percent over the 12 months.

“Birth rates provide insight into long-term population growth as well as the current confidence of Australian families,” said Mr Rawnsley. “We haven’t seen such a sharp drop in births in Australia since the period of economic stagflation in the 1970s, which coincided with the initial widespread adoption of the contraceptive pill.”

Mr Rawnsley said many Australian couples delayed starting a family while the pandemic played out in 2020. The number of births fell from 305,832 in 2019 to 294,369 in 2020. Then in 2021, strong employment and vast amounts of stimulus money, along with high household savings due to lockdowns, gave couples better financial means to have a baby. This led to a rebound in births.

However, the re-opening of the global economy in 2022 led to soaring inflation. By the start of 2023, the Australian consumer price index (CPI) had risen to its highest level since 1990 at 7.8 percent per annum. By that stage, the Reserve Bank had already commenced an aggressive rate-hiking strategy to fight inflation and had raised the cash rate every month between May and December 2022.

Five more rate hikes during 2023 put further pressure on couples with mortgages and put the brakes on family formation. “This combination of the pandemic and rapid economic changes explains the spike and subsequent sharp decline in birth rates we have observed over the past four years,” Mr Rawnsley said.

The impact of high costs of living on couples’ decision to have a baby is highlighted in births data for the capital cities. KPMG estimates there were 60,860 births in Sydney in 2023, down 8.6 percent from 2019. There were 56,270 births in Melbourne, down 7.3 percent. In Perth, there were 25,020 births, down 6 percent, while in Brisbane there were 30,250 births, down 4.3 percent. Canberra was the only capital city where there was no fall in the number of births in 2023 compared to 2019.

“CPI growth in Canberra has been slightly subdued compared to that in other major cities, and the economic outlook has remained strong,” Mr Rawnsley said. “This means families have not been hurting as much as those in other capital cities, and in turn, we’ve seen a stabilisation of births in the ACT.”

This stylish family home combines a classic palette and finishes with a flexible floorplan

Just 55 minutes from Sydney, make this your creative getaway located in the majestic Hawkesbury region.