‘Envy of the World’—U.S. Economy Expected to Keep Powering Higher

Economists lift their growth forecasts in latest Wall Street Journal survey

It has been two years since forecasters felt this good about the economic outlook.

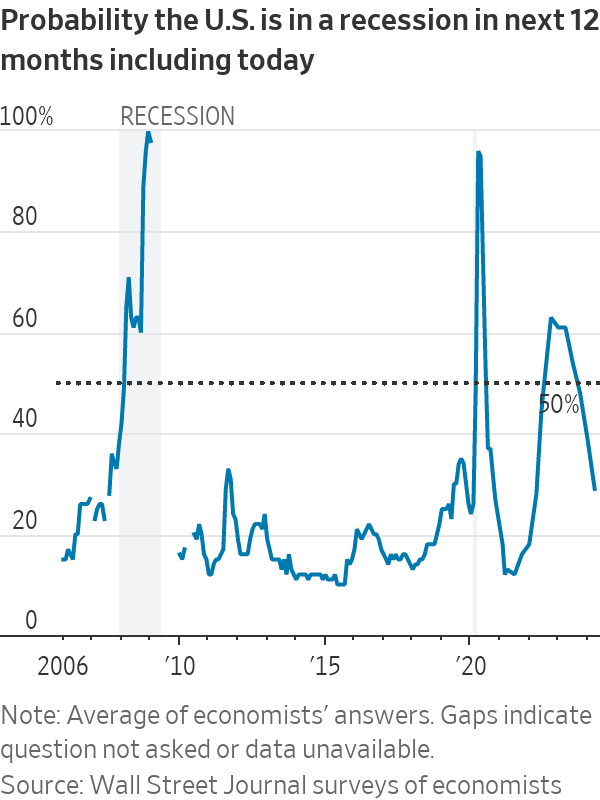

In the latest quarterly survey by The Wall Street Journal, business and academic economists lowered the chances of a recession within the next year to 29% from 39% in the January survey . That was the lowest probability since April 2022, when the chances of a recession were set at 28%.

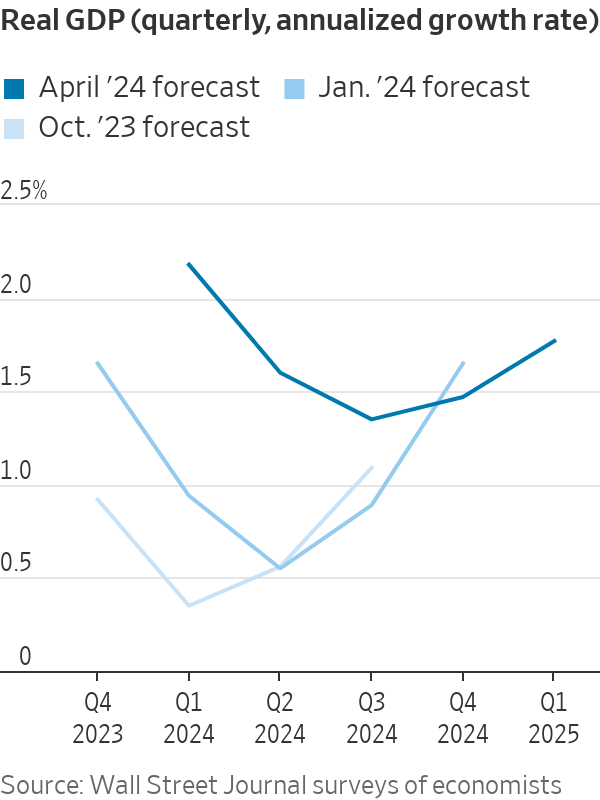

Economists, in fact, don’t think the economy will get even close to a recession. In January, they on average forecast sub-1% growth in each of the first three quarters of this year. Now, they expect growth to bottom out this year at an inflation-adjusted 1.4% in the third quarter.

Just 10% of survey respondents think the economy will experience at least one quarter of negative growth over the next 12 months, down from 33% in January.

The Wall Street Journal survey was conducted from April 5 to 9, just before the release of March consumer-price index data showing inflation running hotter than economists had anticipated.

The U.S. economy has far outperformed expectations over the past year and a half. Instead of stumbling under the weight of the Federal Reserve’s most aggressive interest-rate-raising campaign in four decades, it has continued expanding at a robust clip.

Few think that the economy can do quite as well as last year’s 3.1% growth, as measured by the seasonally adjusted fourth-quarter change from a year earlier. That figure might have been boosted by one-time factors such as federal infrastructure and semiconductor legislation and an uptick in immigration , which also might not last.

Still, economists have had to rethink forecasts for a major slowdown as more time has passed and one still doesn’t seem imminent. Economists on average think the economy grew at a 2.2% rate in the first three months of the year, up from a 0.9% forecast in January.

“The U.S. economy is performing very well,” EconForecaster economist James Smith said in the survey. “We’re truly the envy of the world.”

Much has changed since economists were last this optimistic. Two years ago, the Fed’s benchmark federal-funds rate was set between 0.25% and 0.5%. Inflation was high but economists still generally thought that it could come down without too much help from the Fed. They forecast steady growth and the midpoint of the range for the fed-funds rate topping out at just above 2.5%.

Now, the fed-funds rate is sitting between 5.25% and 5.5%, and economists don’t see a bunch of cuts coming soon. Many analysts trimmed their rate-cut forecasts after last week’s hot inflation report. But even before the report, survey respondents predicted that rates would end the year at 4.67%, implying three cuts. In January, their responses suggested that they thought four or five cuts were likely.

Economists now think the economy can withstand higher rates than they did not long ago.

They expect the 10-year Treasury yield—a key borrowing benchmark that was around 4.4% at the time of the survey—to end 2024 at 3.97%. Looking further into the future, they expect the yield to end 2026 at 3.78%. That is slightly above even their forecast last October, when the yield was higher than it is now.

Many economists have long thought that the economy can handle higher interest rates when it is capable of growing faster, and particularly when worker productivity has increased.

To that end, economists expect the Labor Department’s measure of productivity to rise at an annual rate of 1.9% over the next decade. That matches the annual increase in productivity over the last 40 years. But it is above the 1.2% pace of the 2010s, when the 10-year Treasury yield was typically stuck between 1.5% and 2.5%.

Some economists are now enthusiastic about the economy’s longer-term potential.

“We think that the American economy has entered a virtuous cycle where strong productivity results in growth above the long-term trend, inflation between 2% and 2.5% and an unemployment rate between 3.5% and 4%,” RSM US chief economist Joe Brusuelas said in the survey.

Many aren’t quite as optimistic. One downside of a better growth outlook is that a stronger economy could make it harder for inflation to fall all the way back to the Fed’s 2% target.

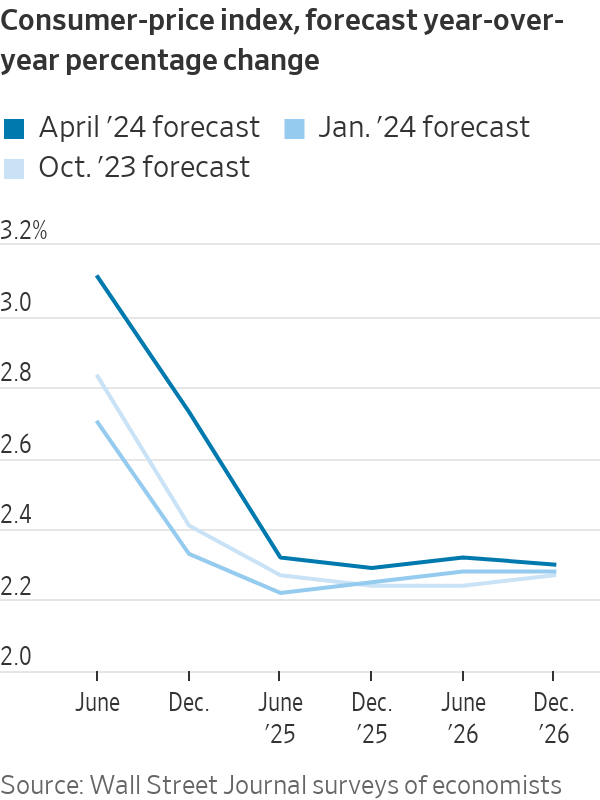

An inflation gauge that is closely watched by the Fed, the core personal-consumption expenditures price index, was 2.8% in February, its most recent reading. Economists now expect it to end the year at 2.5%, after having forecast 2.3% in January.

Economists, on average, believe that core PCE inflation will fall to 2.1% by the end of next year without a recession. However, their projections might already have ticked higher after last week’s price data, and some continue to worry that the Fed’s efforts to control inflation still present a major threat to the economy.

“The risks are clearly skewed toward more hawkish Fed outcomes, which could drag on our growth forecasts,” Deutsche Bank economists Brett Ryan and Matthew Luzzetti said in the survey.

The Wall Street Journal survey was answered by 69 economists. Not every economist responded to every question.

Copyright 2020, Dow Jones & Company, Inc. All Rights Reserved Worldwide. LEARN MORE

Copyright 2020, Dow Jones & Company, Inc. All Rights Reserved Worldwide. LEARN MORE

This stylish family home combines a classic palette and finishes with a flexible floorplan

Just 55 minutes from Sydney, make this your creative getaway located in the majestic Hawkesbury region.

Continued stagflation and cost of living pressures are causing couples to think twice about starting a family, new data has revealed, with long term impacts expected

Australia is in the midst of a ‘baby recession’ with preliminary estimates showing the number of births in 2023 fell by more than four percent to the lowest level since 2006, according to KPMG. The consultancy firm says this reflects the impact of cost-of-living pressures on the feasibility of younger Australians starting a family.

KPMG estimates that 289,100 babies were born in 2023. This compares to 300,684 babies in 2022 and 309,996 in 2021, according to the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS). KPMG urban economist Terry Rawnsley said weak economic growth often leads to a reduced number of births. In 2023, ABS data shows gross domestic product (GDP) fell to 1.5 percent. Despite the population growing by 2.5 percent in 2023, GDP on a per capita basis went into negative territory, down one percent over the 12 months.

“Birth rates provide insight into long-term population growth as well as the current confidence of Australian families,” said Mr Rawnsley. “We haven’t seen such a sharp drop in births in Australia since the period of economic stagflation in the 1970s, which coincided with the initial widespread adoption of the contraceptive pill.”

Mr Rawnsley said many Australian couples delayed starting a family while the pandemic played out in 2020. The number of births fell from 305,832 in 2019 to 294,369 in 2020. Then in 2021, strong employment and vast amounts of stimulus money, along with high household savings due to lockdowns, gave couples better financial means to have a baby. This led to a rebound in births.

However, the re-opening of the global economy in 2022 led to soaring inflation. By the start of 2023, the Australian consumer price index (CPI) had risen to its highest level since 1990 at 7.8 percent per annum. By that stage, the Reserve Bank had already commenced an aggressive rate-hiking strategy to fight inflation and had raised the cash rate every month between May and December 2022.

Five more rate hikes during 2023 put further pressure on couples with mortgages and put the brakes on family formation. “This combination of the pandemic and rapid economic changes explains the spike and subsequent sharp decline in birth rates we have observed over the past four years,” Mr Rawnsley said.

The impact of high costs of living on couples’ decision to have a baby is highlighted in births data for the capital cities. KPMG estimates there were 60,860 births in Sydney in 2023, down 8.6 percent from 2019. There were 56,270 births in Melbourne, down 7.3 percent. In Perth, there were 25,020 births, down 6 percent, while in Brisbane there were 30,250 births, down 4.3 percent. Canberra was the only capital city where there was no fall in the number of births in 2023 compared to 2019.

“CPI growth in Canberra has been slightly subdued compared to that in other major cities, and the economic outlook has remained strong,” Mr Rawnsley said. “This means families have not been hurting as much as those in other capital cities, and in turn, we’ve seen a stabilisation of births in the ACT.”

This stylish family home combines a classic palette and finishes with a flexible floorplan

Just 55 minutes from Sydney, make this your creative getaway located in the majestic Hawkesbury region.