European Central Bank Raises Key Interest Rate to Record High

Central bank signals this might be enough to combat inflation, but doesn’t rule out further increases

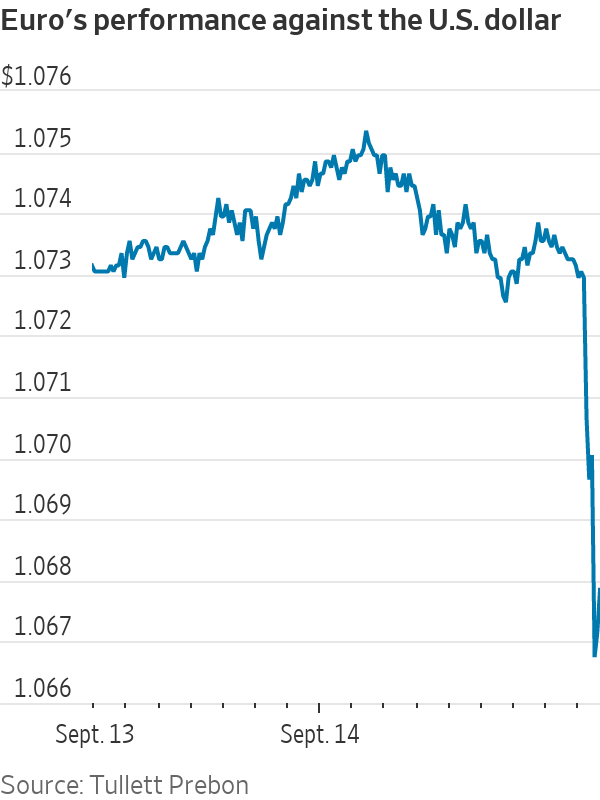

FRANKFURT—The European Central Bank raised interest rates by a quarter percentage point to a record high but signalled that eurozone borrowing costs may have peaked, sending the euro tumbling.

In a split decision, ECB officials raised the bank’s deposit rate to 4%, the 10th increase in a row and a vertiginous rise from below zero last year.

At a news conference, ECB President Christine Lagarde signalled that Thursday’s rate increase might be the last, although she didn’t rule out further hikes if economic data disappoint.

ECB officials judge that rates “have reached levels that, maintained for a sufficiently long duration, will make a substantial contribution” to reducing inflation to their 2% target, Lagarde said, repeating language used in the bank’s policy statement.

The comment prompted investors to downgrade their expectations for future ECB rates, sending the euro down by almost a cent against the dollar to below $1.07, its lowest level since March. Bond yields slid, with yields on the benchmark 10-year government bonds of Germany, France and Italy down between 0.05 and 0.10 percentage point. European stocks rallied, with the benchmark Stoxx Europe 600 index rising more than 1%.

The eurozone still has lower interest rates than the U.S., as well as higher inflation and a struggling economy that contrasts with relatively healthy economic growth in the U.S.—all factors that are weighing on the euro.

“In all likelihood the ECB is done,” said Frederik Ducrozet, head of macroeconomic research at Pictet Wealth Management in Geneva.

Major central banks including the Federal Reserve are signalling a possible halt to a historic series of interest-rate increases over the past 18 months aimed at tackling a surge in inflation unseen since the 1970s.

Ending rate increases would favour borrowers amid uncertainty in the global economy, declining international trade and faltering industrial output. However, signalling a peak in interest rates now risks letting excessive inflation on both sides of the Atlantic become entrenched. Some central banks, including those of Australia and Canada, signalled a pause in recent months, only to start raising rates again.

Recent market movements suggest investors are now betting that rates will peak and even start falling as early as next spring as inflation and economic growth both come down.

They expect the ECB to hold interest rates at about 4% through next summer before starting to cut them, according to data from Refinitiv. They think the Fed will hold rates steady in a range between 5.25% and 5.5% at its meeting next week, and to start cutting rates early next year. The Bank of England is expected to increase interest rates at least once more this year before cutting them later next year.

Investors had been unusually divided before Thursday’s decision over whether the ECB would pause already or unveil one last rate increase. That disagreement reflects uncertainty over how much a slowdown in eurozone growth, together with the ECB’s past rate increases, will cool the region’s inflation rate, which stood at 5.3% in August, unchanged from a month earlier.

Lagarde said some of the central bank’s governors would have preferred to hold rates steady at this month’s meeting. However, a “solid majority” of them agreed on the decision to take rates higher, she said.

New economic forecasts published by the ECB Thursday suggested that eurozone growth will slow significantly more than previously expected this year and next, while inflation will remain markedly above the ECB’s target of 2% through next year. The bank raised its forecast for inflation next year from 3% to 3.2%, mainly to reflect “a higher path for energy prices.”

Asked about the prospect of rate cuts, Lagarde replied that “is not even a word we have pronounced.”

“The longer they can keep interest rates at elevated levels, the more insurance they buy against a downturn down the road,” said Robert Dishner, a senior portfolio manager at Neuberger Berman. “If they end up cutting too soon, they risk reigniting inflation.”

Central banks in Europe face a particularly daunting challenge because while recent interest rate rises have weighed heavily on lending and probably lowered economic growth, they have yet to show a marked effect on underlying inflation. This contrasts with the U.S., where the Fed has taken interest rates higher than the ECB and underlying inflation has fallen significantly while the nation’s growth remains robust. Underlying inflation in August was 5.3% in the eurozone and 4.3% in the U.S.

Recent data and business surveys signal a darkening economic outlook for Europe amid weak growth in China and a decline in global manufacturing. The eurozone economy has largely stagnated since late last year, and industrial production declined in July, dragged down by weakness in Germany, the region’s largest economy.

Lagarde warned that Europe is currently going through a phase of very sluggish growth and suggested that the ECB’s rate hikes are filtering through to the economy. “We are beginning to see weakness in the volume of hires particularly in the services sector that is related to manufacturing,” she said.

Meanwhile, a recent increase in oil prices is pushing inflation in the wrong direction. The euro has slumped against the dollar in recent weeks, to around $1.07 from $1.12 in July, as the eurozone’s economic prospects have soured. That increases the cost of imported goods, making the ECB’s job harder.

Matthew Ryan, head of market strategy at financial-services firm Ebury, said the ECB would likely start cutting rates later, and possibly at a more gradual pace, than the Fed, which should support the euro.

Some of the economic weakening is as intended. The ECB expects its rate increases to slow the region’s economy by weighing on asset prices and demand for loans. However, it isn’t clear if inflation is starting to fall because of the ECB’s actions or because of other factors, such as the fact natural-gas prices are dramatically lower compared with last year, when Russia throttled Europe’s gas supplies. This makes it hard to predict if the region’s economic slowdown will push inflation all the way down to 2%.

Market confidence in the ECB’s ability to achieve its objectives is gradually eroding, with the closely watched five-year, five-year inflation swap—a gauge of expected inflation over a 10-year horizon—standing at 2.6%, according to Franck Dixmier, global chief investment officer for fixed income at Allianz Global Investors.

High current and expected future inflation could mean that investors are underestimating the potential for further ECB rate increases, Dixmier said.

Copyright 2020, Dow Jones & Company, Inc. All Rights Reserved Worldwide. LEARN MORE

Copyright 2020, Dow Jones & Company, Inc. All Rights Reserved Worldwide. LEARN MORE

This stylish family home combines a classic palette and finishes with a flexible floorplan

Just 55 minutes from Sydney, make this your creative getaway located in the majestic Hawkesbury region.

Continued stagflation and cost of living pressures are causing couples to think twice about starting a family, new data has revealed, with long term impacts expected

Australia is in the midst of a ‘baby recession’ with preliminary estimates showing the number of births in 2023 fell by more than four percent to the lowest level since 2006, according to KPMG. The consultancy firm says this reflects the impact of cost-of-living pressures on the feasibility of younger Australians starting a family.

KPMG estimates that 289,100 babies were born in 2023. This compares to 300,684 babies in 2022 and 309,996 in 2021, according to the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS). KPMG urban economist Terry Rawnsley said weak economic growth often leads to a reduced number of births. In 2023, ABS data shows gross domestic product (GDP) fell to 1.5 percent. Despite the population growing by 2.5 percent in 2023, GDP on a per capita basis went into negative territory, down one percent over the 12 months.

“Birth rates provide insight into long-term population growth as well as the current confidence of Australian families,” said Mr Rawnsley. “We haven’t seen such a sharp drop in births in Australia since the period of economic stagflation in the 1970s, which coincided with the initial widespread adoption of the contraceptive pill.”

Mr Rawnsley said many Australian couples delayed starting a family while the pandemic played out in 2020. The number of births fell from 305,832 in 2019 to 294,369 in 2020. Then in 2021, strong employment and vast amounts of stimulus money, along with high household savings due to lockdowns, gave couples better financial means to have a baby. This led to a rebound in births.

However, the re-opening of the global economy in 2022 led to soaring inflation. By the start of 2023, the Australian consumer price index (CPI) had risen to its highest level since 1990 at 7.8 percent per annum. By that stage, the Reserve Bank had already commenced an aggressive rate-hiking strategy to fight inflation and had raised the cash rate every month between May and December 2022.

Five more rate hikes during 2023 put further pressure on couples with mortgages and put the brakes on family formation. “This combination of the pandemic and rapid economic changes explains the spike and subsequent sharp decline in birth rates we have observed over the past four years,” Mr Rawnsley said.

The impact of high costs of living on couples’ decision to have a baby is highlighted in births data for the capital cities. KPMG estimates there were 60,860 births in Sydney in 2023, down 8.6 percent from 2019. There were 56,270 births in Melbourne, down 7.3 percent. In Perth, there were 25,020 births, down 6 percent, while in Brisbane there were 30,250 births, down 4.3 percent. Canberra was the only capital city where there was no fall in the number of births in 2023 compared to 2019.

“CPI growth in Canberra has been slightly subdued compared to that in other major cities, and the economic outlook has remained strong,” Mr Rawnsley said. “This means families have not been hurting as much as those in other capital cities, and in turn, we’ve seen a stabilisation of births in the ACT.”

This stylish family home combines a classic palette and finishes with a flexible floorplan

Just 55 minutes from Sydney, make this your creative getaway located in the majestic Hawkesbury region.