Stressed-Out Americans Plan to Buy Fewer Christmas Gifts, Donate Less to Charity

Inflation is souring the holiday season, a crucial time when companies, charities and nonprofits typically collect their biggest haul of the year

Households, retailers and charities nationwide, feeling the pinch of inflation, are bracing for a humbug holiday season.

U.S. consumers and businesses have trimmed spending plans for gifts, charitable contributions and holiday events, data show. The penny-pinching threatens to spoil the year-end for many, especially firms and nonprofits that tally their largest share of sales and donations in November and December.

“We’re hopeful for a strong giving season, but we’re not counting on it,” said Thomas Tighe, chief executive of Direct Relief, a medical-assistance nonprofit that takes in around $2 billion a year in donated medicine, supplies and cash to deliver help around the world.

Opal Holt-Philip’s children—ages 5, 9 and 12—will be among those taking the brunt of rising prices. Ms. Holt-Philip has always made sure the children woke on Christmas to piles of presents under the tree, just as she did growing up. Ms. Holt-Philip and her husband, Anthony Philip, typically save for months and shop early to check off wish lists. In past years, that meant more than 20 small presents per child. Not this time.

Rent on the family’s two-bedroom Miami apartment rose to $2,600 a month this spring from $1,365 when they arrived in 2020. With the added pressure of trying to save for a house, Ms. Holt-Philip, a 33-year-old wellness blogger, said she asked her children to settle on one “really good gift” apiece. She and her husband agreed to skip gifts for each other this year.

It all feels wrong, Ms. Holt-Philip said, but “we have to eat.”

Consumer prices have risen faster than wages this year, and high inflation has proved more persistent than many policy makers expected. The high cost of living has unnerved consumers, despite a strong job market, a cushion of household savings built up during the Covid-19 pandemic and a few signs that inflation is slowing.

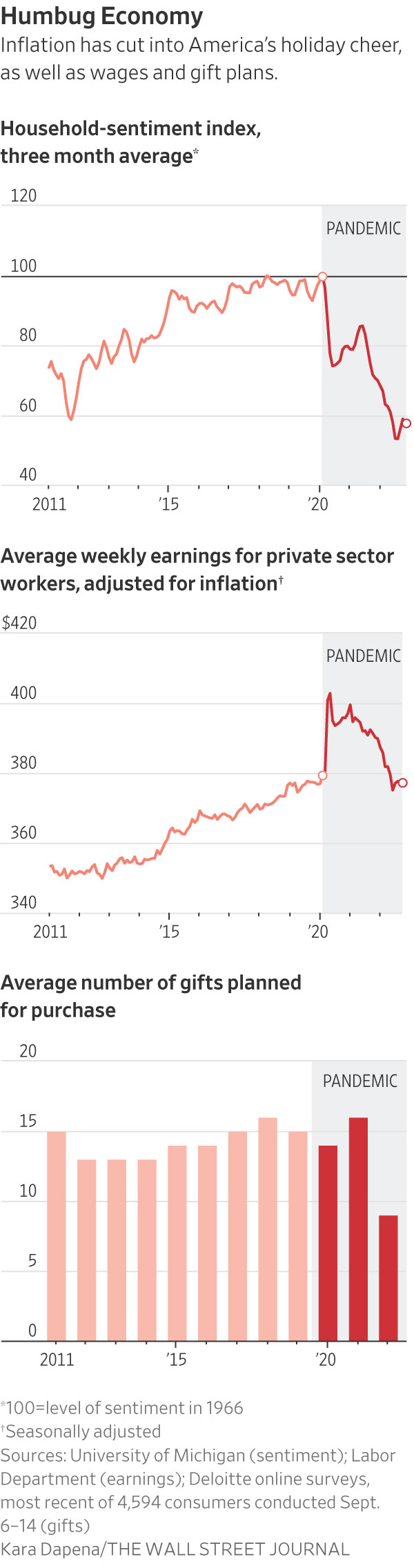

The University of Michigan estimated that household sentiment in the past six months is comparable to late 2008 and early 2009, when the financial system verged on economic disaster and unemployment was soaring. The index also echoes wary levels of the 1970s, when inflation climbed to double digits.

A Census Bureau survey of households in early October found that 41% of Americans, around 95 million people, said they were having difficulty paying for essential household expenses, compared with 29% a year earlier.

People plan to buy an average of nine gifts this year compared with 16 last year, according to Deloitte consulting’s 37th annual holiday shopping survey of 5,000 respondents in September. Total anticipated spending per household was $1,455, down from $1,463 a year ago, Deloitte said. People in the survey said they also planned to spend less time shopping than they did last year.

The Conference Board, a nonprofit research organization that surveys household confidence each month, said individuals had cut gift spending plans to $613 this year from $648 in 2021. Home décor, furniture, appliances, jewelry and tools are among the categories facing the biggest cuts.

In an August survey of 2,415 adults by Bankrate, the consumer finance website, 84% of holiday shoppers said they would pursue money-saving tactics this year—relying on coupons and discounts, buying fewer items, shopping for cheaper gifts and cheaper brands or making presents themselves.

Of course, the outlook might shift. Economists have found that households don’t always do what they say on survey answers. A drop in gasoline and food prices or a bump in the stock market could boost holiday spending. A recent government report showed retail sales picked up in October, in part because of higher prices.

The best news would likely be a measure of relief from inflation.

‘Mom guilt’

After raising prices for months, some firms are betting that markdowns will buck up sales and clear inventory.

The Toy Association, which represents companies responsible for 96% of all toys sold in the U.S., forecasts a season of price cuts. Apparel prices also are headed down, according to DataWeave Inc., an analytics company that tracks online prices for thousands of retail items. Gap Inc. is offering discounts as high as 60%, a level of savings virtually impossible to find during last year’s holiday season, when supply-chain problems left retailers short of inventory.

Target Corp. executives said last week that consumers have pulled back on spending, sapping sales and profits, and prompting the company to plan discounts to clear out unwanted inventory during the holidays.

Many independent stores can’t afford deep discounts. Keri Piehl, owner of Color Wheel Toys in Albuquerque, N.M., said she had strong sales last year but worries about customers shopping online or at big-box retailers this year. To cut costs, she stopped ordering large paper bags for customer purchases, and, to save on shipping, she is buying more items in bulk. Ms. Piehl said she was storing the extra merchandise in her home office.

High inflation seemed to restrain holiday-season shopping over the past eight decades. Eleven times since World War II, the consumer-price index has equaled or exceeded 6% around holiday time; this year it was at 7.7% as of October. Consumer spending had an average growth rate of 1.2% in those years, compared with a rate of 3.4% in years with lower inflation, Commerce Department data show.

American consumer spending has been on a downward trend for months. After jumping by more than 8% last year, adjusted for inflation, consumer spending grew less than 2% during the first nine months of this year.

“I’m not canceling Christmas. I’m not the Grinch,” Richard House, chief executive of FlexShopper Inc., a Boca Raton, Fla.-based online retailer serving consumers with low credit ratings, told analysts this month. “But we’re cautious regarding the amount of volume that may be there.”

Michael Liersch, a financial planning specialist at Wells Fargo, guides the bank’s army of local advisers in branches around the U.S. He said he was struck by the number of families talking about scaling back this year.

Some are taking children to stores to learn exactly what they want. “No surprises, really keeping it very practical,” Mr. Liersch said. “If you recall 10, 20 to 30 years ago, there was a notion where families had relatives give essential items. Moving back into that. Less discretionary items, more needs.”

Maggie Enriquez, a single mother in Austin, Texas, spent about $1,000 on gifts last year for her 2-year-old daughter, Lela, and her extended family. This year, she plans to wrap toy dinosaurs and games that Lela’s older half-brother doesn’t use anymore for her daughter to open on Christmas.

Ms. Enriquez, 37, is a digital-ad sales development representative at a social-media company, a job she supplements working weekends as an Uber driver to pay for daycare, rent and groceries. Her digital-sales contract is up in March, and she is worried about company budget cuts.

In past years, Ms. Enriquez has contributed to online Christmas wish-list sites and toy drives for children in need. This year, she worries she might have to apply as a recipient rather than a donor.

“I am feeling a bit bereft that I can’t give the way I want to this year,” she said. “I take a lot of pride in being able to provide for my daughter, and when I can’t, I feel really inadequate, and the mom guilt kicks in.”

Tough choices

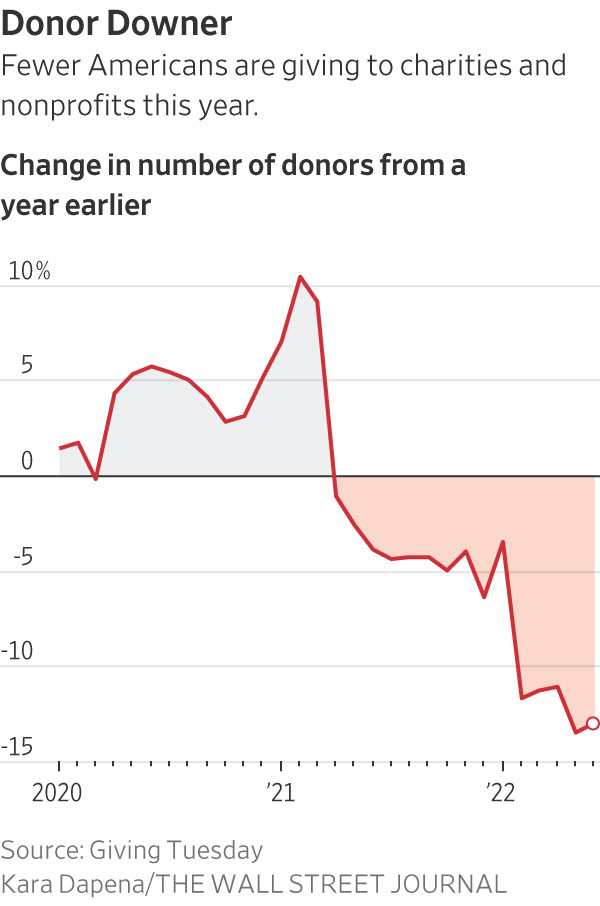

The month between Thanksgiving and Christmas accounts for between 20% and 30% of charitable donations, according to the Giving USA Foundation.

Leaders of the Salvation Army, whose bell-ringing volunteers collect donations from passersby, are worried. Many people are facing a tough holiday season, Commissioner Kenneth G. Hodder said, “particularly those who have to make choices between buying toys, putting food on the table or paying utilities.”

Requests for assistance from people in need in various spots around the U.S. are up 25% to 50% from last year, Mr. Hodder said, and he expects fewer coins and bills getting dropped into the Salvation Army’s red kettles.

Crowdfunding platform Kiva surveyed 2,000 Americans and found that many planned to give less to charity compared with last year: 44% blamed a lack of funds, 42% said donating was “for the privileged.”

GivingTuesday, a nonprofit, and the Association of Fundraising Professionals said the number of donors nationwide fell steeply in the second quarter, driven by declines in donations of less than $500. Fundraising totals were up 6.2% during that time but didn’t keep pace with the second quarter’s inflation rate of more than 8%.

Holiday work parties also are looking less festive. Avital Ungar, a party planner who works with Fortune 500 companies and startups in New York City, San Francisco and Los Angeles, said many clients, facing hiring freezes or layoffs, don’t have the budget for elaborate events this year.

Restaurants around the country are feeling the fallout.

Mani Bhushan, who owns four Mexican restaurants in the Dallas area, said that in prepandemic times he would have received dozens of catering orders for 100-plus person Christmas events by this time in the holiday season. He currently has none. Large-group reservations, he said, are down 95% from 2019.

Overall sales numbers are up, Mr. Bhushan said, but he is barely breaking even because of the rising cost of rent, labor and ingredients. A pound of chicken breast is $4.33 compared with $2.99 a year ago. “I used to pay $14 for a good cook,” he said, and now it is $18 an hour for even a marginal cook.

Ms. Holt-Philip, the Miami wellness blogger, is looking on the bright side. She hopes that her family’s limited budget for gifts will keep the focus on the true meaning of the holidays: spending time together.

For the first time, she, her husband and their three children plan to spend Christmas with a dozen or so relatives at a family cabin in Doniphan, Mo. They will roast marshmallows and play Family Feud in front of the fireplace, Ms. Holt-Philip said. With any luck, the children will see their first snowfall.

“Honestly, if this goes as planned,” she said, “a reduced gift-giving Christmas might become our new normal.”

Copyright 2020, Dow Jones & Company, Inc. All Rights Reserved Worldwide. LEARN MORE

Copyright 2020, Dow Jones & Company, Inc. All Rights Reserved Worldwide. LEARN MORE

This stylish family home combines a classic palette and finishes with a flexible floorplan

Just 55 minutes from Sydney, make this your creative getaway located in the majestic Hawkesbury region.

Continued stagflation and cost of living pressures are causing couples to think twice about starting a family, new data has revealed, with long term impacts expected

Australia is in the midst of a ‘baby recession’ with preliminary estimates showing the number of births in 2023 fell by more than four percent to the lowest level since 2006, according to KPMG. The consultancy firm says this reflects the impact of cost-of-living pressures on the feasibility of younger Australians starting a family.

KPMG estimates that 289,100 babies were born in 2023. This compares to 300,684 babies in 2022 and 309,996 in 2021, according to the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS). KPMG urban economist Terry Rawnsley said weak economic growth often leads to a reduced number of births. In 2023, ABS data shows gross domestic product (GDP) fell to 1.5 percent. Despite the population growing by 2.5 percent in 2023, GDP on a per capita basis went into negative territory, down one percent over the 12 months.

“Birth rates provide insight into long-term population growth as well as the current confidence of Australian families,” said Mr Rawnsley. “We haven’t seen such a sharp drop in births in Australia since the period of economic stagflation in the 1970s, which coincided with the initial widespread adoption of the contraceptive pill.”

Mr Rawnsley said many Australian couples delayed starting a family while the pandemic played out in 2020. The number of births fell from 305,832 in 2019 to 294,369 in 2020. Then in 2021, strong employment and vast amounts of stimulus money, along with high household savings due to lockdowns, gave couples better financial means to have a baby. This led to a rebound in births.

However, the re-opening of the global economy in 2022 led to soaring inflation. By the start of 2023, the Australian consumer price index (CPI) had risen to its highest level since 1990 at 7.8 percent per annum. By that stage, the Reserve Bank had already commenced an aggressive rate-hiking strategy to fight inflation and had raised the cash rate every month between May and December 2022.

Five more rate hikes during 2023 put further pressure on couples with mortgages and put the brakes on family formation. “This combination of the pandemic and rapid economic changes explains the spike and subsequent sharp decline in birth rates we have observed over the past four years,” Mr Rawnsley said.

The impact of high costs of living on couples’ decision to have a baby is highlighted in births data for the capital cities. KPMG estimates there were 60,860 births in Sydney in 2023, down 8.6 percent from 2019. There were 56,270 births in Melbourne, down 7.3 percent. In Perth, there were 25,020 births, down 6 percent, while in Brisbane there were 30,250 births, down 4.3 percent. Canberra was the only capital city where there was no fall in the number of births in 2023 compared to 2019.

“CPI growth in Canberra has been slightly subdued compared to that in other major cities, and the economic outlook has remained strong,” Mr Rawnsley said. “This means families have not been hurting as much as those in other capital cities, and in turn, we’ve seen a stabilisation of births in the ACT.”

This stylish family home combines a classic palette and finishes with a flexible floorplan

Just 55 minutes from Sydney, make this your creative getaway located in the majestic Hawkesbury region.