The Art Market Is Tanking. Sotheby’s Has Even Bigger Problems.

The auction house, owned by highly leveraged billionaire Patrick Drahi, is pushing off payments, awaiting a financial lifeline from an Abu Dhabi fund

The art market is grinding through a rough patch, and no one is feeling the pain more than Sotheby’s.

The sales downturn, driven in part by China’s economic slowdown, wars and volatile U.S. elections, has hit at a crunchtime for the auction house’s highly leveraged billionaire owner, Patrick Drahi , who is fighting fires amid restructuring in his broader telecom empire, Altice .

Sotheby’s had been riding a rollicking art market wave in recent years, bringing in at least $7 billion in sales annually and setting record-level prices for trophies by Gustav Klimt and René Magritte.

Now, amid signs cash is running low, it is pushing off payments to its art shippers and conservators by as much as six months. Several former and current employees said Sotheby’s this spring gave senior staffers IOUs instead of their incentive pay. And at a meeting this month of higher-ranking executives, some executives expressed worries about whether the company would be able to keep paying its employees on time, according to a person familiar with the discussion.

Drahi has at the same time been under pressure to slash the crushing debt of roughly $60 billion at Altice. The conglomerate’s French arm is now going through restructuring talks with creditors, with the U.S. arm expected to enter restructuring talks later. Some Wall Street analysts had hoped Drahi might sell part of Sotheby’s to help bolster Altice.

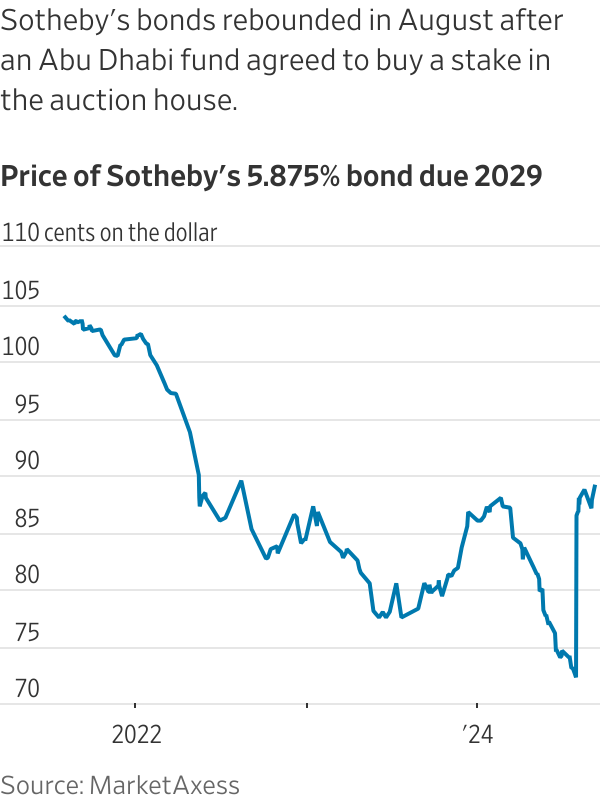

Sotheby’s itself carries $1.8 billion in debt, almost double the level it had before the Franco-Israeli billionaire purchased it in 2019. The value of its bonds swooned in the first half of the year as investors worried that declining sales and higher interest rates would choke off the company’s cash flow.

The auction house received a lifeline with a $1 billion deal to sell a stake to Abu Dhabi sovereign-wealth fund ADQ , announced Aug. 9 but not expected to close until later this year. At the time, Drahi said he would contribute an undisclosed amount as part of the deal.

As it awaits the funds, Sotheby’s is toeing a high-wire act with an uncertain outcome.

Charles Stewart , Sotheby’s chief executive, dismissed fears about Sotheby’s financial standing as overblown, and the company disputed the meeting with higher-ranking executives occurred. Stewart said the company’s bonds, which have rebounded in price since the ADQ rescue was announced, are proof that Sotheby’s has smoothed over any worries. He said the ADQ investment will position the house for growth moving forward. “It’s a massive credit positive,” he said.

A Sotheby’s spokeswoman said: “Under Mr. Drahi’s ownership, Sotheby’s is significantly larger, more diversified and more profitable than ever before. During this period, we have invested hundreds of millions to enhance our facilities, technology and expand our offerings to clients.”

ADQ declined to comment.

The crisis at Sotheby’s comes at a time when the entire art market is reeling . Over the past year, collectors who see art as a financial asset have winced as higher interest rates and inflation made it more expensive to trade art. Contemporary art buyers have also suffered sticker shock after years of paying ever-higher prices for emerging artists—who may never pay off. Some smaller galleries, who rely on collectors to vouch for unknown artists, have shuttered, while dealers have reported lacklustre sales at art fairs.

Those factors have hurt collectors’ overall confidence. “I don’t feel like there’s a bunch of collectors waiting out there to save the day this time,” said Dallas collector Howard Rachofsky.

Growing debt load

Drahi, 61 years old, is famous for taking on a mountain of debt to build telecommunications empire Altice, which operates in the U.S. and Europe. He borrowed from Wall Street when interest rates were low, but now that rates have risen sharply, he has started selling off chunks of his companies to lower his debt burden. Last month, his Altice UK sold a 24.5% stake in its BT Group to the Indian international investment arm of Bharti Enterprises in a deal valued at roughly $4 billion.

Drahi used a similar high-debt strategy to buy Sotheby’s in 2019 for $2.7 billion. Drahi issued $1.1 billion in new bonds and loans to finance the deal, and separately also assumed some portion of Sotheby’s existing $1 billion debt.

He has since spent lavishly, including signing a deal to pay at least $100 million for New York’s Breuer building, a Madison Avenue showpiece once home to the Whitney Museum of American Art and temporarily used by both the Metropolitan Museum of Art and Frick Collection. The company is planning to move in at the end of next year and to lease out part of its current glassy headquarters closer to the East River in Manhattan. Sotheby’s has spent tens of millions more to renovate new luxury-retail-style spaces in Paris and Hong Kong.

Drahi also expanded Sotheby’s ability to auction multimillion-dollar homes by buying a chunk of real-estate seller Concierge, and added RM Sotheby’s, an entity that sells high-end cars.

At the same time, the owner has pulled funds out of the company via dividends. In total since the purchase, Sotheby’s has paid out $1.2 billion of dividends to a parent company controlled by Drahi, according to New Street Research.

The ballooning debt didn’t draw much attention during flush years when an influx of newly wealthy collectors from across China, Russia, the Middle East and even the world of cryptocurrency were clamouring after Sotheby’s offerings.

That changed when the market cooled. Sotheby’s told its bondholders the auction portion of the business had a loss of $115 million in the first half of the year, compared to a $3 million profit in the first half of 2023, according to a copy of Sotheby’s unaudited financials for the first half of the year reviewed by The Wall Street Journal.

Rival Christie’s, owned by luxury magnate François Pinault , has also taken a hit, with its auction sales dropping nearly a quarter during the first half of the year.

Sotheby’s adjusted operating free cash flow fell to $144 million in the 12 months ended June 30, a 43% decline from the same time last year, according to data from New Street Research. The figure measures whether a company is making enough money to pay its bills and turn a profit.

Credit rating firm Moody’s Investors Service in February knocked down the ratings for Sotheby’s bonds to B3, one of its lowest categories of junk debt, specifically citing the dividends paid out. “The downgrade also reflects governance considerations, particularly the company’s decision to continue dividend payments out of its credit group in 2023 despite its operating performance deterioration,” Moody’s said in its decision. S&P downgraded the debt into deep junk territory in June.

Stewart said the company’s credit rating has been lower since the Drahi purchase. He said its updates to bondholders revolve around its auction performance only and don’t include fees from the company’s real-estate holdings or financial-services arm, which Stewart said remain in the black. He declined to divulge the company’s full financial figures.

Stewart also said the dividends remain in the Sotheby’s ecosystem and aren’t being redirected to shore up Drahi or his other businesses.

Drahi’s arrival

Sotheby’s was flush with cash but lagging behind Christie’s in 2018 when Tad Smith, the auction house’s then-CEO, suggested to his board that it find a buyer. The company had been public for three decades, but Smith believed the demands for public shareholder returns hampered its ability to go toe-to-toe with the bigger and privately held Christie’s.

In early 2019, the board let Smith make overtures to prospective buyers, including an entity connected to Abu Dhabi’s royal family that expressed interest, according to a person familiar with the negotiations. Drahi moved more quickly and emerged as the winner.

At first, the art establishment didn’t know much about Drahi. The self-made billionaire was born in Morocco, educated in France and has homes in Switzerland and Israel. He was familiar to Sotheby’s staffers in their Tel Aviv office but wasn’t widely known in art circles.

At the time, he was a traditional collector of 19th- and 20th-century artists rather than trendier, contemporary ones, owning pieces by Pablo Picasso, Henri Matisse and Marc Chagall. But he didn’t sit on major museum boards or pop up regularly on the art-fair circuit.

The Sotheby’s purchase marked Drahi’s first foray into luxury. The art world wondered if he would manage a house that started off auctioning books in London in 1744 the same way he ran his broadband communications companies, where he was known for aggressively cutting costs and using debt to fuel ambitious expansions.

Drahi told Sotheby’s he saw the company as an investment for his family, regularly dismissing rumors he was teeing up Sotheby’s to be resold. In 2021, Sotheby’s promoted his son Nathan, then 26, to run Sotheby’s operations in Asia, a key market.

As part of the sale, Sotheby’s divided its various endeavors—such as its real-estate arm and its financial services arm, which lends against people’s art collections—into affiliated but separate entities from the main unit, which handles Sotheby’s auctions and private art sales.

Stewart said Drahi’s move was intended to keep each division nimble.

The art-world ecosystem noticed Drahi’s arrival in other ways. Soon after the sale, a network of smaller companies that auction houses typically enlist to conserve, frame, crate and ship its art around the world said they got word that the house would be lengthening its pay schedules, from a typical month to two or more. One conservator said payments started to arrive six months after a job was completed.

Sotheby’s also started paying sellers more slowly than its rivals. In the past, both Sotheby’s and Christie’s asked winning bidders to pay for their pieces within 30 business days of a sale, and then paid sellers five days later. Sotheby’s changed its contracts to allow it to pay sellers 15 days later, according to sellers familiar with the house’s contracts. The move allowed the house to hold the funds in its coffers longer.

Sotheby’s said its processing deadlines have been in place for many years to allow the company to adequately process payments.

Pay for top talent

When the pandemic hit, Drahi and his management team reoriented the company to sell art online, a pivot Sotheby’s is credited with embracing faster than its rivals.

Sotheby’s also started laying off staff during the lockdown, and continued to do so after the pandemic. When the ever-swirling calendar of fairs and museum openings and biennials got under way again, advisers including Philip Hoffman of the Fine Art Group said they noticed fewer Sotheby’s staffers turned up. The company would send one or two rainmakers, not a whole team.

Stewart confirmed the pandemic-related staff cuts “like many other companies” and winnowed travel were meant to make the company more efficient, though he said it remains “mission critical” to put its top specialists in front of collectors.

Drahi needed Sotheby’s key dealmakers to remain in place. High-end art deals at auction houses are wrangled primarily by a handful of executives and specialists able to cultivate an air-kiss closeness with collectors. They also must be able to discern a fake Picasso from a real one, and price it to sell well in good markets and bad.

In 2021, Drahi revised the incentive pay program for these top performers. In exchange for accepting an immediate pay cut of up to 20%, employees were told they could expect a cash payout in three years based on the company’s performance and representing up to half of their total compensation.

Some powerful executives still left, dealing a blow to the auction house. Patti Wong , Sotheby’s former international chairman for Asia, now works as a private adviser, and Brooke Lampley , its former global chairman of fine art, is now a senior director at the blue-chip gallery Gagosian.

When the delayed payout came due, staff were told in conference calls—some say last fall and others say in March—that it needed to be postponed; enrollees were issued promissory notes this spring instead, according to several former and current specialists. Specialists said they now are hoping to get paid by year’s end with a portion of the Abu Dhabi funds.

The company disputed the description of the incentive program but declined to give further details.

New fees for sellers

In February, Sotheby’s shocked the art world when it fundamentally restructured the way it collects fees for works that it auctions.

Both Sotheby’s and Christie’s, in efforts to bring sellers to their doors, often waived their fees. They even shared with sellers increasingly fatter slices of the fees they charge buyers—which can add up to roughly 27% to a work’s winning price.

At the same time, buyers have bristled over the fees they pay. Rachofsky, the Dallas collector, said he has long agitated that “auction fees are unsustainably high.”

Sotheby’s new fee plan, which went live in late May, now charges buyers a flat 20% for anything it sells for $6 million or less, and 10% for anything it sells for more. For sellers, Sotheby’s charges a fee of 10% on the first $500,000 of anything it sells for $5 million or less. Terms for larger deals continue to be negotiated.

Christie’s and smaller house Phillips said they also charge an undisclosed seller’s commission, but their fee is negotiable.

Stewart said the goal is to create a system that is “simpler and fairer.”

It’s too soon to tell if Sotheby’s new fee structure will help or hamper its effort to win consignments. Sotheby’s has landed the prized estate of the season, an estimated $200 million collection amassed by Palm Beach beauty mogul Sydell Miller that includes a Claude Monet water lily scene estimated to sell for $60 million. The collection will headline the November sales.

Art adviser Anthony Grant said one of his collectors reasons that Sotheby’s might hustle harder to find bidders for each work now that they’re charging sellers a fee to do so. But Grant said he worries the change could also steer sellers of midmarket pieces to other houses who may not charge them extra for anything.

“It’s one more thing that’s gotten harder for them,” he said of Sotheby’s, where he once worked.

Asia is expected to play a crucial role in Sotheby’s prospects. In recent years, newly wealthy bidders in Asia—spanning mainland China to Seoul to Singapore—have been relied upon to mop up art at the highest levels even when collectors elsewhere held back. Now, China’s economy has slowed, sparking fears about its buyers’ willingness to splurge on blue-chip art.

Instead of scaling back, the major auction houses are all doubling down on the region. Sotheby’s and Christie’s both just opened luxurious new spaces in Hong Kong. Sotheby’s Maison space in Hong Kong’s Central neighborhood, opened in late July, said it has already had 300,000 visitors.

This month, on the eve of what was supposed to be its inaugural fall sale series in Hong Kong, the house announced it was pushing back these sales to November. Advisers who work in the region said the move left the impression that the house had failed to gather enough marquee material.

Sotheby’s said the calendar shift gives it more time to organise shows and a sale lineup, and said the delay wasn’t because the art was too tough to source. It cited its plan to sell an estimated $30 million Mark Rothko from 1954, “Untitled (Yellow and Blue),” in Hong Kong later this year.

Collector and dealer Hong Gyu Shin initially consigned an Oscar Wilde manuscript of “The Picture of Dorian Gray” to Sotheby’s to offer in its Hong Kong sales, he said, but he later changed his mind. He said he wanted the auction house to revel in the piece, which contains Wilde’s own handwritten edits, and he wanted to brainstorm the best way to position it to buyers. Instead, there was little conversation after the paperwork was signed.

“Specialists used to be so excited,” he said, “but now they just slap an estimate on it. When you have historical work, it’s a form of art to sell it.”

Copyright 2020, Dow Jones & Company, Inc. All Rights Reserved Worldwide. LEARN MORE

Copyright 2020, Dow Jones & Company, Inc. All Rights Reserved Worldwide. LEARN MORE

A long-standing cultural cruise and a new expedition-style offering will soon operate side by side in French Polynesia.

The pandemic-fuelled love affair with casual footwear is fading, with Bank of America warning the downturn shows no sign of easing.

The pandemic-fuelled love affair with casual footwear is fading, with Bank of America warning the downturn shows no sign of easing.

The boom in casual footware ushered in by the pandemic has ended, a potential problem for companies such as Adidas that benefited from the shift to less formal clothing, Bank of America says.

The casual footwear business has been on the ropes since mid-2023 as people began returning to office.

Analyst Thierry Cota wrote that while most downcycles have lasted one to two years over the past two decades or so, the current one is different.

It “shows no sign of abating” and there is “no turning point in sight,” he said.

Adidas and Nike alone account for almost 60% of revenue in the casual footwear industry, Cota estimated, so the sector’s slower growth could be especially painful for them as opposed to brands that have a stronger performance-shoe segment. Adidas may just have it worse than Nike.

Cota downgraded Adidas stock to Underperform from Buy on Tuesday and slashed his target for the stock price to €160 (about $187) from €213. He doesn’t have a rating for Nike stock.

Shares of Adidas listed on the German stock exchange fell 4.5% Tuesday to €162.25. Nike stock was down 1.2%.

Adidas didn’t immediately respond to a request for comment.

Cota sees trouble for Adidas both in the short and long term.

Adidas’ lifestyle segment, which includes the Gazelles and Sambas brands, has been one of the company’s fastest-growing business, but there are signs growth is waning.

Lifestyle sales increased at a 10% annual pace in Adidas’ third quarter, down from 13% in the second quarter.

The analyst now predicts Adidas’ organic sales will grow by a 5% annual rate starting in 2027, down from his prior forecast of 7.5%.

The slower revenue growth will likewise weigh on profitability, Cota said, predicting that margins on earnings before interest and taxes will decline back toward the company’s long-term average after several quarters of outperforming. That could result in a cut to earnings per share.

Adidas stock had a rough 2025. Shares shed 33% in the past 12 months, weighed down by investor concerns over how tariffs, slowing demand, and increased competition would affect revenue growth.

Nike stock fell 9% throughout the period, reflecting both the company’s struggles with demand and optimism over a turnaround plan CEO Elliott Hill rolled out in late 2024.

Investors’ confidence has faded following Nike’s December earnings report, which suggested that a sustained recovery is still several quarters away. Just how many remains anyone’s guess.

But if Adidas’ challenges continue, as Cota believes they will, it could open up some space for Nike to claw back any market share it lost to its rival.

Investors should keep in mind, however, that the field has grown increasingly crowded in the past five years. Upstarts such as On Holding and Hoka also present a formidable challenge to the sector’s legacy brands.

Shares of On and Deckers Outdoor , Hoka’s parent company, fell 11% and 48%, respectively, in 2025, but analysts are upbeat about both companies’ fundamentals as the new year begins.

The battle of the sneakers is just getting started.

With two waterfronts, bushland surrounds and a $35 million price tag, this Belongil Beach retreat could become Byron’s most expensive home ever.

Australia’s market is on the move again, and not always where you’d expect. We’ve found the surprise suburbs where prices are climbing fastest.