The World Tied $3.5 Trillion-Plus of Debt to Inflation. The Costs Are Now Adding Up.

With roughly $770 billion of borrowings linked to retail prices, Britain is feeling the pinch

Governments and companies around the world spent decades loading up on trillions of dollars of debt whose interest costs rise and fall alongside inflation. But what served as cheap funding when prices were stagnant has rapidly become more expensive.

The inflation-linked headache echoes the broader challenges arising at the end of more than a decade of global easy money, in which debtors borrowed vast amounts at very low, and sometimes negative, interest rates. Investors are on alert for financial vulnerabilities after a crisis in U.S. regional banks this year, and with strains emerging in commercial property.

Borrowing costs of all sorts have risen sharply for governments, businesses and consumers, as central banks have raised key interest rates to combat price pressures. Rates have surged on inflation-linked borrowings, but these aren’t the only source of pain.

As standard bonds with fixed rates mature, they need to be replaced with more expensive new debt. Meanwhile, interest rates on loans are often floating, meaning they quickly reflect changes in policy rates.

Yields on benchmark 10-year fixed-rate bonds, a proxy for government borrowing costs, have climbed to about 4.3% for the U.K. and 3.9% for the U.S. Both were below 1% during the pandemic.

Governments will pay roughly $2.2 trillion in overall debt interest this year, Fitch Ratings estimates. The U.S. Treasury’s interest cost grew 25% to $652 billion in the nine months through June. Germany’s debt-servicing bill is expected to soar to 30 billion euros this year, or some $33.2 billion, from €4 billion in 2021.

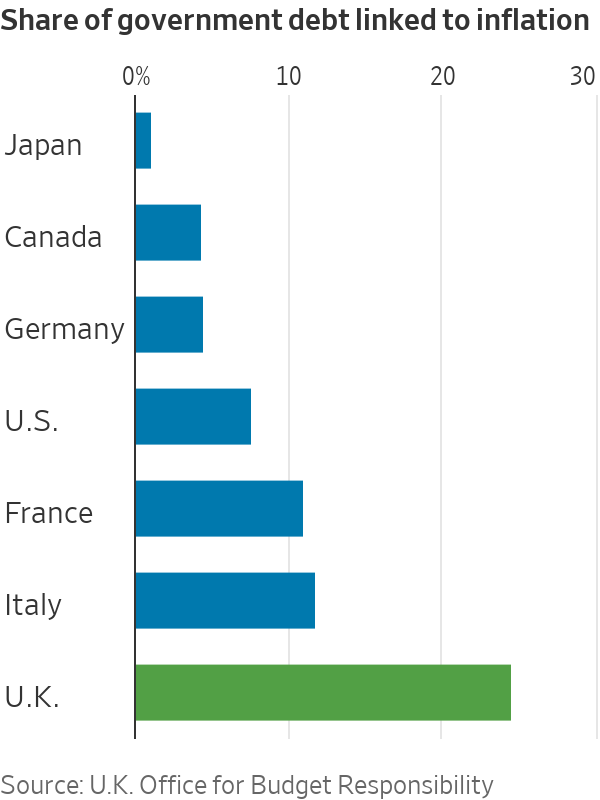

Governments had $3.5 trillion in outstanding inflation-linked debt at the end of 2022, according to the Bank for International Settlements, equivalent to about 11% of their total borrowings.

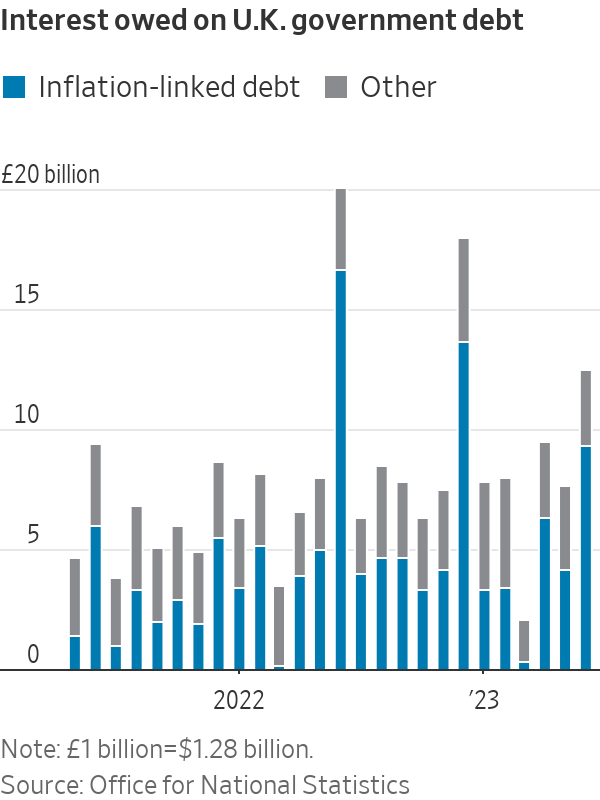

The poster child for the inflation-linked problem is Britain, which has experienced the fastest rise in debt costs in the Group of Seven advanced democracies. The U.K. first embraced such debt under Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher and in 1981 became one of the first developed economies to issue inflation-linked debt: securities that are known as linkers there and Treasury Inflation-Protected Securities, or TIPS, in the U.S. Both the amount due to investors once the bonds mature and the regular interest payments they receive move with inflation.

About a quarter of U.K. debt is now tied to inflation, trailing only a handful of emerging markets with a history of runaway prices such as Uruguay, Brazil and Chile.

“We stick out like a sore thumb,” said Sanjay Raja, chief U.K. economist at Deutsche Bank.

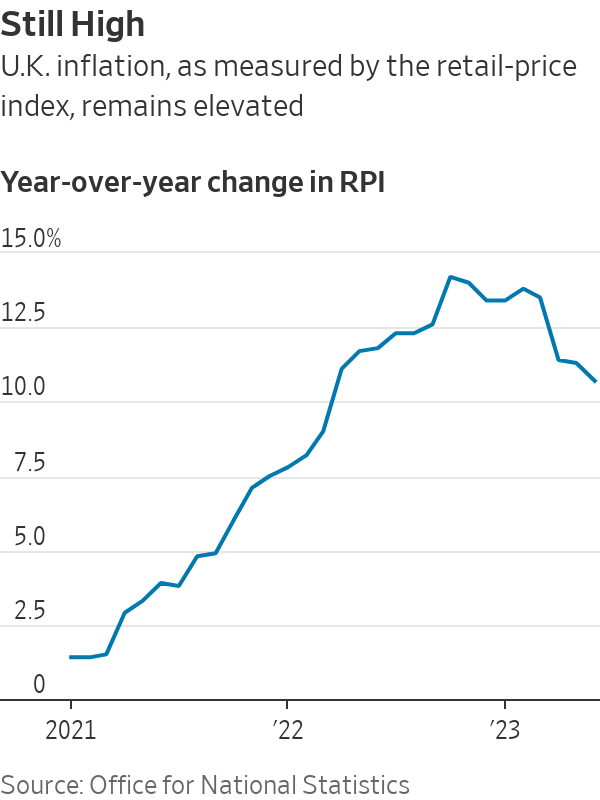

The U.K.’s debt woes are complicated by its longstanding reliance on a measure of price increases that has fallen out of favour: the retail price index, or RPI. Some 600 billion pounds, equivalent to roughly $770 billion, of bonds are linked to this gauge, which has consistently risen faster than more widely used consumer-price indexes. London has pledged to phase out RPI by 2030.

Inflation as measured by the RPI topped 14% in October and was still 11% in June compared with a year earlier. Economists expect U.K. inflation to keep falling this year, albeit more slowly than in other major economies.

In theory, higher interest payouts should be balanced by rising revenue. While higher inflation means bigger payouts to bondholders, it should also bring in more taxes.

That logic holds especially true in markets like the U.K., where inflation gauges are deeply embedded in the economy. Tax thresholds, pension and welfare payments, rail fares and cellphone bills are often linked to price indexes.

But the energy shock that fuelled recent inflation upended that math, since higher energy bills drove up RPI even as earnings and consumer spending lagged behind. The U.K. is experiencing the “wrong sort of inflation,” the U.K.’s Office for Budget Responsibility said this month. The sensitivity of U.K. debt to inflation was unprecedented, the watchdog said.

The U.K.’s debt sustainability is a focus for investors after a market meltdown last fall, triggered by then-Prime Minister Liz Truss’s tax-cutting plans.

Her successor Rishi Sunak and his Chancellor Jeremy Hunt have sought to restore market confidence with pledges to contain inflation and bring down debt. As the U.K.’s interest costs climb, and with debt now surpassing 100% of gross domestic product, those promises are getting harder to keep while maintaining investor confidence.

The debt burden also undermines Sunak’s hopes to woo voters and revive the economy with tax cuts and spending measures ahead of a general election expected to take place next year.

“We could quickly be in a situation where we’re facing some renewed sense of crisis, particularly with an economic backdrop of stagflation with really weak growth and overshooting inflation,” said Mark Dowding, chief investment officer at RBC BlueBay Asset Management in London. “Further policy missteps could easily be punished by the market.”

Higher bond yields and stickier inflation will add an extra £30 billion to the U.K.’s annual government debt bill, estimates Bank of America economist Robert Wood.

“The government has three options: You can plan for weaker spending, you could raise taxes or you could borrow more,” he said. “Certainly one could say that this rise in debt-interest costs is incompatible with cutting taxes.”

The U.K. is selling fewer linkers, which are likely to make up 11% of bond issuance this fiscal year, down from above 20% throughout the 2010s.

One veteran U.K. central banker said linkers had largely done their job as envisioned in the 1980s.

“We were coming out of a decade in which inflation had been extremely high. People were very skeptical about the ability of any government, particularly the Conservative government, to bring inflation down to a low and stable rate,” said Charles Goodhart, who was an adviser at the Bank of England between 1969 and 1985.

Fears that linkers would lead to fresh wage-price spirals as unions demanded inflation-linked increases, didn’t play out, he said. Thatcher, who called inflation “the destroyer of all,” saw linkers as “sleeping policemen,” ensuring the government wasn’t tempted to let inflation run to help inflate debt away.

“It makes the current fiscal position more difficult. But that’s what Mrs. Thatcher actually wanted,” said Goodhart. “She wanted governments to resist inflation more strongly.”

Companies are also feeling the pressure from inflation-linked borrowing. The U.K.’s largest water company, Thames Water, nearly collapsed in recent weeks as investors questioned its ability to repay £14 billion in debt, about half of which is linked to inflation. Thames Water’s debt is RPI-linked, but customer prices now track CPI, which lags behind the RPI by about 3 percentage points more slowly.

Copyright 2020, Dow Jones & Company, Inc. All Rights Reserved Worldwide. LEARN MORE

Copyright 2020, Dow Jones & Company, Inc. All Rights Reserved Worldwide. LEARN MORE

This stylish family home combines a classic palette and finishes with a flexible floorplan

Just 55 minutes from Sydney, make this your creative getaway located in the majestic Hawkesbury region.

Continued stagflation and cost of living pressures are causing couples to think twice about starting a family, new data has revealed, with long term impacts expected

Australia is in the midst of a ‘baby recession’ with preliminary estimates showing the number of births in 2023 fell by more than four percent to the lowest level since 2006, according to KPMG. The consultancy firm says this reflects the impact of cost-of-living pressures on the feasibility of younger Australians starting a family.

KPMG estimates that 289,100 babies were born in 2023. This compares to 300,684 babies in 2022 and 309,996 in 2021, according to the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS). KPMG urban economist Terry Rawnsley said weak economic growth often leads to a reduced number of births. In 2023, ABS data shows gross domestic product (GDP) fell to 1.5 percent. Despite the population growing by 2.5 percent in 2023, GDP on a per capita basis went into negative territory, down one percent over the 12 months.

“Birth rates provide insight into long-term population growth as well as the current confidence of Australian families,” said Mr Rawnsley. “We haven’t seen such a sharp drop in births in Australia since the period of economic stagflation in the 1970s, which coincided with the initial widespread adoption of the contraceptive pill.”

Mr Rawnsley said many Australian couples delayed starting a family while the pandemic played out in 2020. The number of births fell from 305,832 in 2019 to 294,369 in 2020. Then in 2021, strong employment and vast amounts of stimulus money, along with high household savings due to lockdowns, gave couples better financial means to have a baby. This led to a rebound in births.

However, the re-opening of the global economy in 2022 led to soaring inflation. By the start of 2023, the Australian consumer price index (CPI) had risen to its highest level since 1990 at 7.8 percent per annum. By that stage, the Reserve Bank had already commenced an aggressive rate-hiking strategy to fight inflation and had raised the cash rate every month between May and December 2022.

Five more rate hikes during 2023 put further pressure on couples with mortgages and put the brakes on family formation. “This combination of the pandemic and rapid economic changes explains the spike and subsequent sharp decline in birth rates we have observed over the past four years,” Mr Rawnsley said.

The impact of high costs of living on couples’ decision to have a baby is highlighted in births data for the capital cities. KPMG estimates there were 60,860 births in Sydney in 2023, down 8.6 percent from 2019. There were 56,270 births in Melbourne, down 7.3 percent. In Perth, there were 25,020 births, down 6 percent, while in Brisbane there were 30,250 births, down 4.3 percent. Canberra was the only capital city where there was no fall in the number of births in 2023 compared to 2019.

“CPI growth in Canberra has been slightly subdued compared to that in other major cities, and the economic outlook has remained strong,” Mr Rawnsley said. “This means families have not been hurting as much as those in other capital cities, and in turn, we’ve seen a stabilisation of births in the ACT.”

This stylish family home combines a classic palette and finishes with a flexible floorplan

Just 55 minutes from Sydney, make this your creative getaway located in the majestic Hawkesbury region.