U.S. Inflation Slowed for Sixth Straight Month in December

Consumer-price index rose 6.5% last month from a year earlier

U.S. inflation eased in December for the sixth straight month following a mid-2022 peak as the Federal Reserve aggressively raised interest rates and the economy showed signs of cooling.

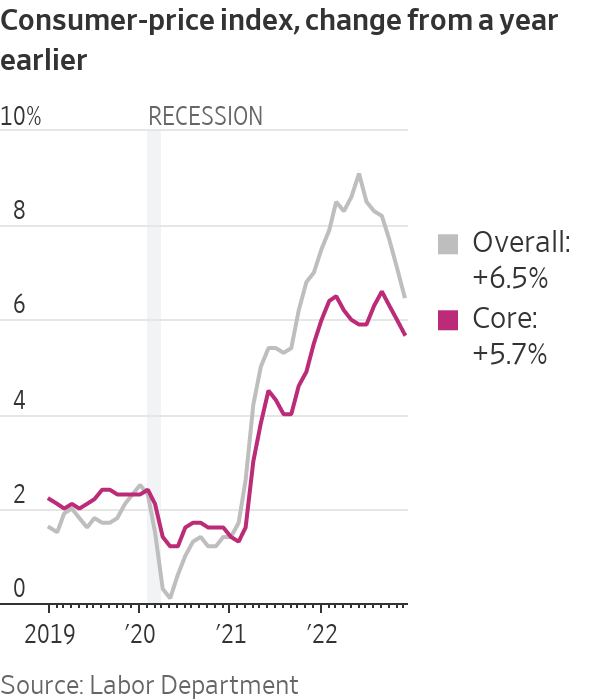

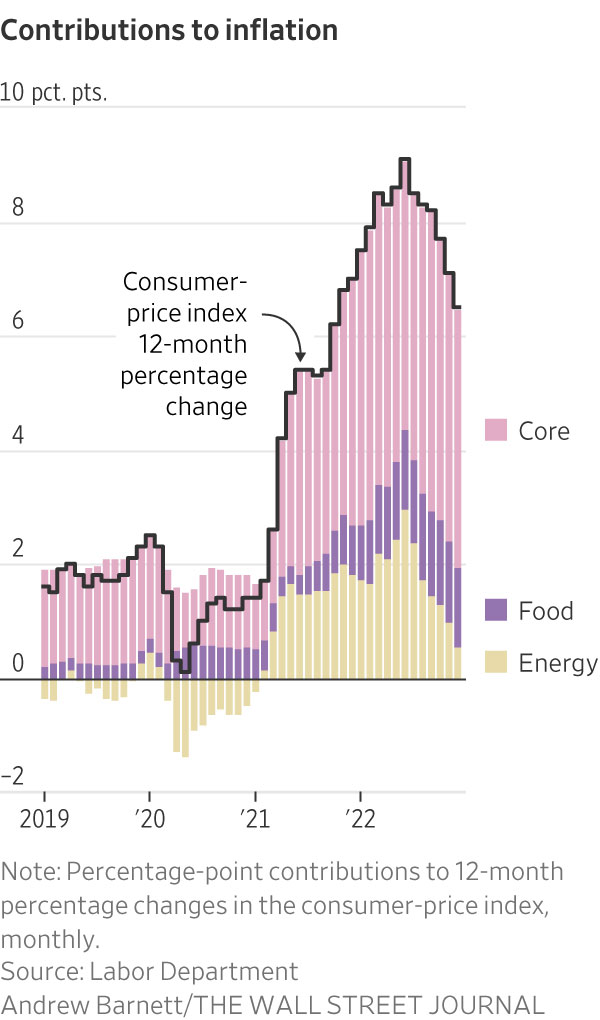

The consumer-price index, a measurement of what consumers pay for goods and services, rose 6.5% last month from a year earlier, down from 7.1% in November and well below a 9.1% peak in June.

Core CPI, which excludes volatile energy and food prices, climbed 5.7% in December from a year earlier, easing from a 6% gain in November. Many economists see increases in core CPI as a better signal of future inflation than the overall CPI. Core prices increased at a 3.1% annualised rate in the three months ended in December, the slowest pace in more than a year and down from 7.9% in June.

The figures added to signs that inflation is turning a corner following last year’s surge. They also likely keep the Fed on track to reduce the size of interest-rate increases to a quarter-percentage-point at their meeting that concludes on Feb. 1, down from a half-percentage point increase in December.

U.S. stocks climbed Thursday and investors bought U.S. Treasurys, lifting bond prices and weighing on yields. The S&P 500 added 0.3%, while the Dow Jones Industrial Average gained 0.6%, or 217 points. The technology-heavy Nasdaq Composite also rose 0.6%.

Easing inflation follows several signs that U.S. economic activity cooled in late 2022. U.S. imports and exports fell in November from October, while retail sales, manufacturing output and home sales all declined. Job and wage growth slowed in December, though the labor market remained tight with historically low claims for unemployment insurance at the start of the year.

“The December CPI report was welcome good news after a very bad patch for inflation,” said Bill Adams, chief economist at Comerica Bank. He said consumers are getting relief from lower gasoline prices and moderating food prices, as well as declining prices for other goods.

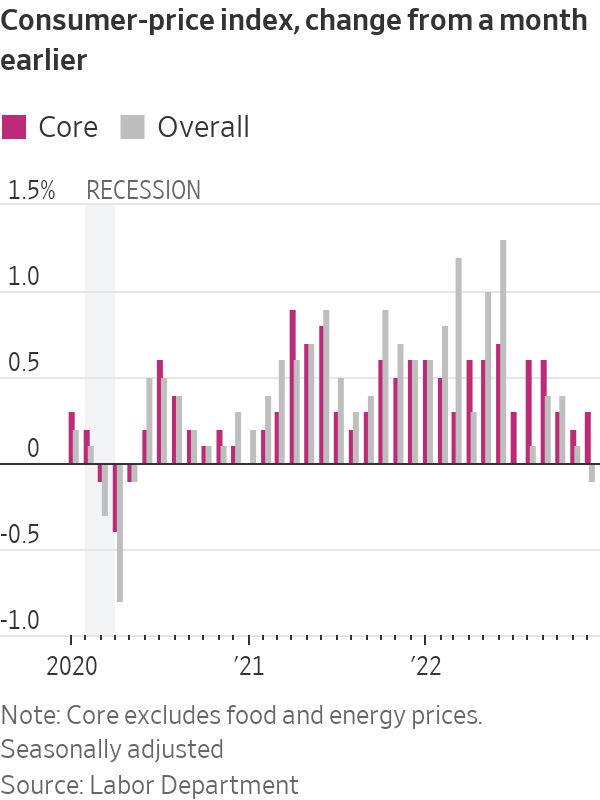

On a monthly basis, the CPI fell 0.1% in December, due to sharply falling energy prices. That compared with a gain of 0.1% in November and 0.4% in October. Food-price increases also slowed last month. Core CPI rose 0.3% in December, up from November’s 0.2% rise but down from 0.6% increases in August and September.

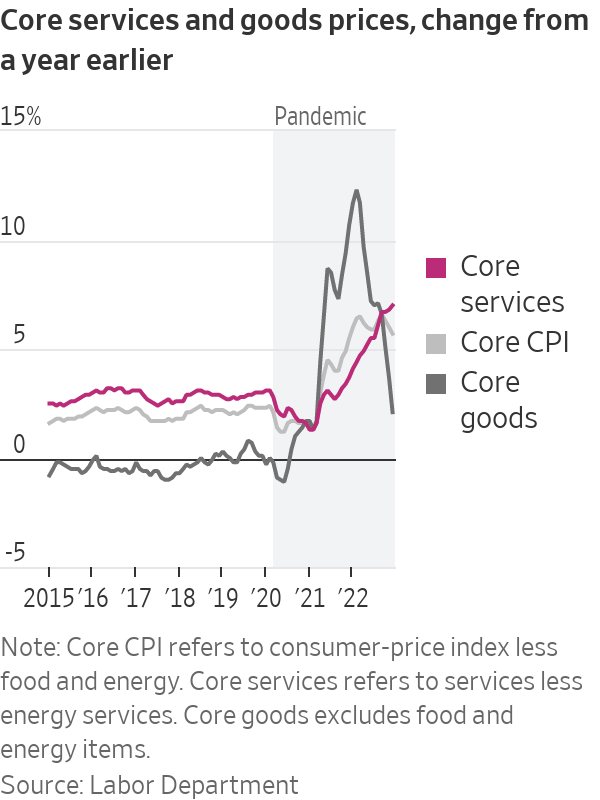

Goods prices, a key driver of inflation over the past year and a half, fell for the third straight month in December as prices fell for products such as autos, computers and sporting goods.

Improving supply chains and reduced demand have relieved price pressures on goods, but services prices continued to climb in part because of wage gains in a tight labour market.

Some economists worry that still-high wage growth could keep consumers flush with cash and companies eager to raise prices to compensate, holding inflation above the Fed’s 2% target.

“Taming services inflation will be the Fed’s biggest challenge this year,” said Ryan Sweet, chief U.S. economist at Oxford Economics.

Shelter prices rose 7.5% in December from a year earlier, the Labor Department said, and a broader measure of services prices that excludes utilities rose 7% during the same period. Both increases were the biggest since 1982.

Daycare and preschool prices rose 5.4% in December from a year earlier, the biggest increase since 2006, while those for home-health care increased 6.1% in the same period. Hospital services prices, meanwhile, jumped 1.5% in December from the prior month, the sharpest monthly increase since 2015.

Inflation remained high across the globe in November, though it abated during the month, the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development said Tuesday. Consumer prices across the Group of 20 largest economies—which contribute four-fifths of economic output worldwide—rose 9% from a year earlier in November, down from October’s 9.5% increase, the first drop in the G-20 inflation rate since August 2021.

Prices rose sharply in 2021 as the U.S. economy rebounded from the Covid-19 pandemic, powered by pent-up consumer spending that got a boost from low interest rates and government stimulus. Snarled supply chains fueled higher prices for many goods. Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in early 2022 also tightened supplies of energy and other commodities, further stoking inflation worldwide.

Inflation pressures on goods dissipated last summer as supply chains improved and energy prices fell. Shipping costs from China to the West Coast are near pre pandemic levels. Gasoline prices have declined, with the national average price of regular unleaded gasoline at $3.27 a gallon on Thursday, down about 50 cents a gallon from mid-November, according to OPIS, an energy-data and analytics provider. Gasoline prices peaked in mid-June at a record $5.02 a gallon.

“Logistics prices have also slowed materially, shipping costs are back to where they were pre-Covid,” said Jake Oubina, senior economist at Piper Sandler. “The alleviation on the cost side is creating the wherewithal to discount more aggressively as we head into 2023.”

The clearest impact of Fed tightening so far is in the housing market. Existing-home sales fell in November for a 10th straight month as high mortgage rates boosted buyers’ costs.

Ian Snowden, a 33-year-old tech salesman, said the shift to remote work after the pandemic hit allowed him to move to Asheville, N.C., where he has easy access to hiking, fishing and other outdoor activities.

The move proved expensive, though. After losing out to cash buyers in bids for existing homes, Mr. Snowden signed a contract in September 2021 to buy a newly constructed property. By the time his home was completed the following June, mortgage rates had doubled. On top of that, the construction company told him that he was on the hook for an extra $25,000 to offset unexpectedly high costs for concrete, labor and other items—or he could back out of the contract.

At that point, Mr. Snowden said, he was already selling his old house and had made plans to move, so he wasn’t going to back out. “So much was already in motion,” he said. Between the higher mortgage rates and the additional costs, the monthly mortgage payment increased $200, he said.

—Austen Hufford contributed to this article.

Copyright 2020, Dow Jones & Company, Inc. All Rights Reserved Worldwide. LEARN MORE

Copyright 2020, Dow Jones & Company, Inc. All Rights Reserved Worldwide. LEARN MORE

This stylish family home combines a classic palette and finishes with a flexible floorplan

Just 55 minutes from Sydney, make this your creative getaway located in the majestic Hawkesbury region.

Continued stagflation and cost of living pressures are causing couples to think twice about starting a family, new data has revealed, with long term impacts expected

Australia is in the midst of a ‘baby recession’ with preliminary estimates showing the number of births in 2023 fell by more than four percent to the lowest level since 2006, according to KPMG. The consultancy firm says this reflects the impact of cost-of-living pressures on the feasibility of younger Australians starting a family.

KPMG estimates that 289,100 babies were born in 2023. This compares to 300,684 babies in 2022 and 309,996 in 2021, according to the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS). KPMG urban economist Terry Rawnsley said weak economic growth often leads to a reduced number of births. In 2023, ABS data shows gross domestic product (GDP) fell to 1.5 percent. Despite the population growing by 2.5 percent in 2023, GDP on a per capita basis went into negative territory, down one percent over the 12 months.

“Birth rates provide insight into long-term population growth as well as the current confidence of Australian families,” said Mr Rawnsley. “We haven’t seen such a sharp drop in births in Australia since the period of economic stagflation in the 1970s, which coincided with the initial widespread adoption of the contraceptive pill.”

Mr Rawnsley said many Australian couples delayed starting a family while the pandemic played out in 2020. The number of births fell from 305,832 in 2019 to 294,369 in 2020. Then in 2021, strong employment and vast amounts of stimulus money, along with high household savings due to lockdowns, gave couples better financial means to have a baby. This led to a rebound in births.

However, the re-opening of the global economy in 2022 led to soaring inflation. By the start of 2023, the Australian consumer price index (CPI) had risen to its highest level since 1990 at 7.8 percent per annum. By that stage, the Reserve Bank had already commenced an aggressive rate-hiking strategy to fight inflation and had raised the cash rate every month between May and December 2022.

Five more rate hikes during 2023 put further pressure on couples with mortgages and put the brakes on family formation. “This combination of the pandemic and rapid economic changes explains the spike and subsequent sharp decline in birth rates we have observed over the past four years,” Mr Rawnsley said.

The impact of high costs of living on couples’ decision to have a baby is highlighted in births data for the capital cities. KPMG estimates there were 60,860 births in Sydney in 2023, down 8.6 percent from 2019. There were 56,270 births in Melbourne, down 7.3 percent. In Perth, there were 25,020 births, down 6 percent, while in Brisbane there were 30,250 births, down 4.3 percent. Canberra was the only capital city where there was no fall in the number of births in 2023 compared to 2019.

“CPI growth in Canberra has been slightly subdued compared to that in other major cities, and the economic outlook has remained strong,” Mr Rawnsley said. “This means families have not been hurting as much as those in other capital cities, and in turn, we’ve seen a stabilisation of births in the ACT.”

This stylish family home combines a classic palette and finishes with a flexible floorplan

Just 55 minutes from Sydney, make this your creative getaway located in the majestic Hawkesbury region.