Wall Street’s Next Big Play Is Garbage

Landfill firms are investing in trash-gas production and recycling technology

The green push by the U.S. and state governments is turning trash into treasure and boosting the firms that handle America’s garbage.

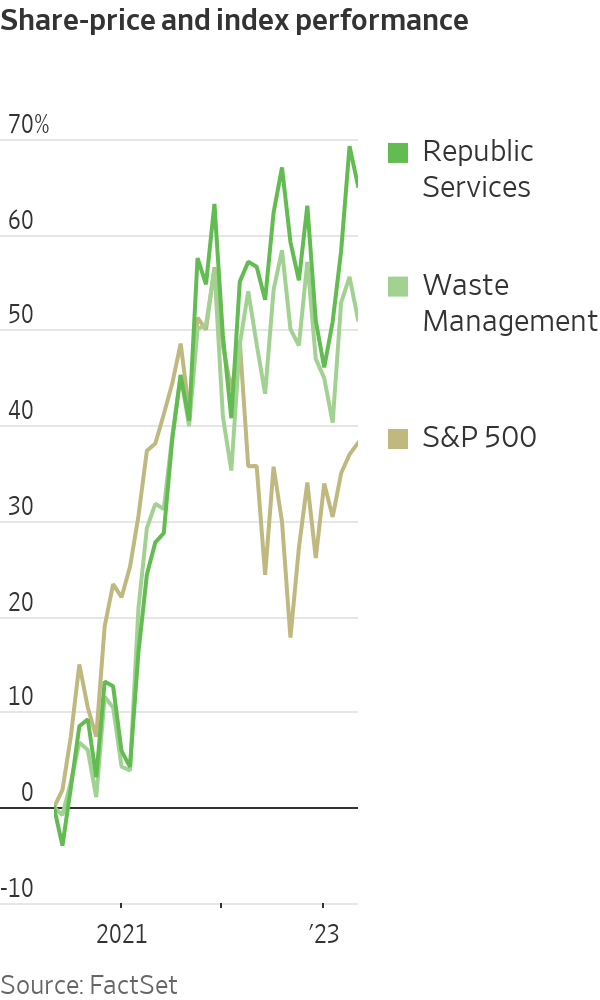

Shares of the biggest players in the U.S. trash business, Waste Management and Republic Services, have traded at record highs since President Biden signed the climate, tax and healthcare bill in August. A recent decline notwithstanding, the stocks are popular picks on Wall Street to ride the sustainability boom higher.

“They’re sitting in this extraordinary position,” said Michael Hoffman, an analyst at investment bank Stifel. “Garbage will be on the forefront.”

Efforts to reduce greenhouse-gas emissions and to reuse materials are making it more profitable to mine landfills for energy and sift through refuse for the hot commodities of the green economy, such as detergent bottles and cardboard boxes.

WM and Republic are building plants to isolate methane from the fumes emitted by rotting garbage and pipe it into the natural-gas grid to be burned in power plants, furnaces and kitchens. They are also equipping recycling facilities with the latest in automation to better sort and process materials for the consumer-goods companies that are under pressure to keep their packaging out of landfills and the ocean.

Landfill owners are forecasting hundreds of millions of dollars in additional profit from rising demand for recycled materials and tax incentives for making energy from emissions that would otherwise seep into the atmosphere.

“We’re blessed to be sitting right in the middle of a megatrend,” Republic Chief Executive Jon Vander Ark said. “We used to think about getting 5% top-line growth a year; now we’re in double-digit top-line growth mode.”

Republic, which has 206 active landfills, has a joint venture with a unit of BP to install gasworks at 43 of its dumps. The Phoenix firm has 65 landfill-gas plants. Some feed utility pipelines. Others generate electricity on site.

Republic is also spending about $275 million to build four polymer-processing facilities that will sort the plastic it collects kerbside and turn it into flakes for new bottles and jugs.

Vander Ark said consumer-product companies face minimum post-consumer-content mandates in California, Washington and other states, as well as their own sustainability goals. Republic’s first plastics plant is scheduled to open later this year in Las Vegas. Customers lined up.

“There’s fighting among customers about who gets what,” Vander Ark said.

Analysts say one risk is that adding exposure to volatile markets for commodities and renewable-fuel credits might spook investors interested in the steady and predictable profits involved in dumping garbage into landfills. Executives say the sustainability businesses are supplementary and moneymakers even when commodity prices are low, like now.

“Yes, there’s a year-over-year impact, but recycling is still profitable,” said Tara Hemmer, WM’s chief sustainability officer. “It still is one of our highest return-on-capital investments.”

WM, which operates more than 250 landfills, is in the second year of a four-year plan to spend $1.2 billion adding 20 trash-gas plants as well as $1 billion expanding and automating its recycling business.

The Houston company expects new and upgraded facilities to increase its recovery of reusable materials 25% by 2025. Having machines do the dirty work also cuts labor costs, executives say.

A lot of hard-to-fill jobs will be replaced by optical sorters, which use infrared cameras to spot valuable materials in the jumble and blow the desirable bits into separate bins with pinpoint puffs of air, Hemmer said.

“In the past we might have had mixed-paper bales that had cardboard embedded in them,” she said. “Now we’re able to pull more of that cardboard out, it goes in the cardboard bale, and the price point on cardboard is much higher than mixed paper.”

WM says the blended commodity value from its automated material recovery facilities is about 15% higher per ton. Not only do the machines amass more of the valuable stuff, the company says the material emerges cleaner and can fetch more than messy bales.

The recycling investments will add $240 million to its bottom line over the next four years, WM says. It has higher expectations for its gas business.

WM says it will boost landfill-gas output eightfold and generate more than $500 million in additional earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation and amortisation through 2026.

That profit forecast assumes two prices associated with every million British thermal units of gas. WM is counting on the actual fuel selling for $2.50, which is lately about the price of gas from geologic wells. Another $23.50 is anticipated from renewable-fuel credits, which is in line with recent trading, according to energy-information firm Platts.

The outlook doesn’t count the $250 million or more of tax credits WM expects for building new gas plants.

Last year’s climate bill sweetened the economics of trash gas. A federal proposal to offer additional credits for biogas projects that produce power for electric vehicles could make the incentives even stronger.

Waste-company executives and analysts say that many are worth building anyway and that the incentives make it economical to install gasworks at smaller, less-gassy landfills.

“Landfill gas is essentially the only scalable biofuel that doesn’t have a food-for-fuel trade-off,” said Goldman Sachs analyst Jerry Revich. “These projects don’t need any subsidies, but they will take the free money.”

Copyright 2020, Dow Jones & Company, Inc. All Rights Reserved Worldwide. LEARN MORE

Copyright 2020, Dow Jones & Company, Inc. All Rights Reserved Worldwide. LEARN MORE

This stylish family home combines a classic palette and finishes with a flexible floorplan

Just 55 minutes from Sydney, make this your creative getaway located in the majestic Hawkesbury region.

Continued stagflation and cost of living pressures are causing couples to think twice about starting a family, new data has revealed, with long term impacts expected

Australia is in the midst of a ‘baby recession’ with preliminary estimates showing the number of births in 2023 fell by more than four percent to the lowest level since 2006, according to KPMG. The consultancy firm says this reflects the impact of cost-of-living pressures on the feasibility of younger Australians starting a family.

KPMG estimates that 289,100 babies were born in 2023. This compares to 300,684 babies in 2022 and 309,996 in 2021, according to the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS). KPMG urban economist Terry Rawnsley said weak economic growth often leads to a reduced number of births. In 2023, ABS data shows gross domestic product (GDP) fell to 1.5 percent. Despite the population growing by 2.5 percent in 2023, GDP on a per capita basis went into negative territory, down one percent over the 12 months.

“Birth rates provide insight into long-term population growth as well as the current confidence of Australian families,” said Mr Rawnsley. “We haven’t seen such a sharp drop in births in Australia since the period of economic stagflation in the 1970s, which coincided with the initial widespread adoption of the contraceptive pill.”

Mr Rawnsley said many Australian couples delayed starting a family while the pandemic played out in 2020. The number of births fell from 305,832 in 2019 to 294,369 in 2020. Then in 2021, strong employment and vast amounts of stimulus money, along with high household savings due to lockdowns, gave couples better financial means to have a baby. This led to a rebound in births.

However, the re-opening of the global economy in 2022 led to soaring inflation. By the start of 2023, the Australian consumer price index (CPI) had risen to its highest level since 1990 at 7.8 percent per annum. By that stage, the Reserve Bank had already commenced an aggressive rate-hiking strategy to fight inflation and had raised the cash rate every month between May and December 2022.

Five more rate hikes during 2023 put further pressure on couples with mortgages and put the brakes on family formation. “This combination of the pandemic and rapid economic changes explains the spike and subsequent sharp decline in birth rates we have observed over the past four years,” Mr Rawnsley said.

The impact of high costs of living on couples’ decision to have a baby is highlighted in births data for the capital cities. KPMG estimates there were 60,860 births in Sydney in 2023, down 8.6 percent from 2019. There were 56,270 births in Melbourne, down 7.3 percent. In Perth, there were 25,020 births, down 6 percent, while in Brisbane there were 30,250 births, down 4.3 percent. Canberra was the only capital city where there was no fall in the number of births in 2023 compared to 2019.

“CPI growth in Canberra has been slightly subdued compared to that in other major cities, and the economic outlook has remained strong,” Mr Rawnsley said. “This means families have not been hurting as much as those in other capital cities, and in turn, we’ve seen a stabilisation of births in the ACT.”

This stylish family home combines a classic palette and finishes with a flexible floorplan

Just 55 minutes from Sydney, make this your creative getaway located in the majestic Hawkesbury region.