Why Americans Are Obsessed With These Ugly Sandals

Margot Fraser’s feet hurt. Then she found Birkenstocks and brought them to the U.S. Now the company is worth billions of dollars.

One of the iconic shots of the year’s biggest movie was Margot Robbie’s Barbie character in Birkenstocks.

She was only wearing them because of Margot Fraser.

This woman responsible for bringing the supremely comfy, seductively ugly German footwear to the U.S. was one of the most improbable business figures of her time.

She was an accidental entrepreneur who started distributing Birkenstocks from her California home in the 1960s, when nobody knew what they were or how orthopaedic sandals cured foot pain. The only places that would carry them were health-food stores, where each pair might as well have come with a jar of granola. She was a dressmaker with no clue about shoes, much less crunchy ones, but she grew the company from zero to hundreds of millions of dollars in sales. She would even come to be known as Mrs. Birkenstock.

The sandals that she introduced to Americans have become more popular and the business much bigger than Fraser could have predicted. This week, when Birkenstock went public, the company was valued at $8.6 billion.

It’s fitting that Birkenstock’s initial public offering comes on the heels of a summer ruled by the spending power of women because this is a company whose U.S. business has always been built around their needs.

That’s in large part because of Margot Fraser, the most important woman in the company’s history. She paid attention to women—and it paid off. They were her first customers. They were also her best customers. Birkenstock’s financial documents credit “the breakthrough of modern feminism” as a key driver of its business, and the company’s private-equity backers cite the products’ appeal to women as one of the reasons they invested. In fact, Birkenstock says 72% of its customers are female.

It’s a remarkably high number for a company that explicitly markets its products as unisex. Steve Jobs wore them. Sneaker geeks want them. They were designed by Karl Birkenstock, a son of Carl and grandson of Konrad, descendants of the man who started the family’s tradition of shoemaking 249 years ago. More recently, the private-equity firm and family office of Bernard Arnault, the billionaire chief executive of LVMH’s luxury empire, bought a controlling stake and took the company public.

Anyone can now own stock in BIRK because of its connection to one of the world’s richest men, but Birkenstock never would have been in this position without a pioneering woman.

“It is because of Margot and the foundation she built that the brand is enjoying the success that it is today,” the president of the company’s American division said when she died in 2017.

She was the first to admit that she was an unlikely footwear executive and had to learn how to run the business one step at a time.

“I didn’t know a thing about shoes,” she once said. “What I did know was that my feet were always hurting.”

But that was all she needed to know. She figured that millions of women across the country must have feet that were always hurting, too.

Fraser had a keen sense of the American consumer for someone who grew up in war-torn Germany. The principal of her elementary school in the 1930s taught her that “girls were capable of anything and should follow their dreams,” but not everyone in her life agreed. “My mother thought that was all ridiculous feminist stuff,” Fraser wrote in a book offering business advice. Her father wasn’t exactly Betty Friedan, either. When she told him she wanted to travel the world for business and show people that “not all Germans were bad,” he responded: “My dear, you could never do that as a woman.”

She went to dressmaking school and moved to the countryside to make clothing for farmers, who paid her in eggs and butter. It was the teenager’s first taste of entrepreneurship. When she couldn’t see a future in Germany after World War II, she decided to leave home in pursuit of her childhood dream, and she boarded a trans-Atlantic ship with $25 in her pocket.

But it was only when Fraser returned as a tourist nearly 15 years later that she discovered the shoes that would rescue her feet and transform her life.

She was living in the U.S. when she took a spa trip back to Germany in 1966 and came across “sandals that weren’t pretty to look at.” But after years of trying anything to fix her aching feet—even standing on a phone book and gripping it with her toes—she tried on her first Birkenstocks.

She was pain-free within months.

Fraser realised that her feet were always hurting because of her painful footwear. No amount of standing on phone books would have made a difference for women in constrictive heels with pointed toes. What did make the difference for Fraser were these sandals made with leather, cork and a footbed the Birkenstock men invented. They were following in the footsteps of Johannes Birkenstock, which date back to 1774, when the cobbler was mentioned in the church records of a village near Frankfurt. The company’s first sandals were released in 1963, not long before Fraser slipped them on.

They were so comfortable that she didn’t care if they were ugly. Birkenstocks provided value because they solved a problem. They were basically Hokas for hippies.

Fraser took the sandals back to the U.S. and wrote to the Birkenstock family asking if she could sell them to Americans. They said yes to the dressmaker. At first, it seemed unwise. The owners of local shoe stores wouldn’t talk to her, and doctors treated her like a threat to the podiatry business.

She was desperate when a friend mentioned that a group called the Health Food Association was hosting a national convention nearby, which is how she found herself in a San Francisco hotel pitching sandals to people who sold lentils.

She needed to find people who didn’t mind how their shoes looked. As it turns out, they were the kind of people who owned health-food stores. Because they spent all day on their feet, they chose function over fashion. Fraser knew there would be a market for Birkenstocks when she spotted a woman at the convention shuffling around in nylons while carrying shoes that she couldn’t wear.

“The woman tried on a pair,” she wrote, “and bought them despite her husband’s protests.”

Once she had a foothold, Fraser began working out of her Bay Area home in 1967, calling her distribution company Birkenstock Footprint Sandals. She later renamed it Birkenstock USA.

She couldn’t have picked a better time or place for Birkenstocks to come plodding into the U.S. They would have crossed the ocean eventually, but the sandals became a symbol of rebellion because they landed in the heart of the counterculture, when and where people were allergic to the mainstream and willing to wear their antiestablishment values on their feet. “It was this perfect moment,” said Andrea Schneider-Braunberger, the curator of Birkenstock’s historical archives. “The culture was ready for such modern, convention-breaking shoes.”

Fraser worked closely with the Birkenstock family and shared their complete obsession with Birkenstocks. They made the shoes and decisions for the entire company based on her feedback.

The name of the funny-looking sandal that caught her eye was the “Original Birkenstock-Footbed sandal,” but Fraser told her German partners that American women were never going to buy something called “Original Birkenstock-Footbed sandal.” They took her marketing advice and branded the single-strapped sandal the “Madrid.” It remains one of the company’s top sellers.

It took six years for Fraser to venture beyond health-food stores and move into actual footwear stores. But that timing also turned out to be advantageous. By then, people were ready to buy Birkenstocks, and she was better at selling them.

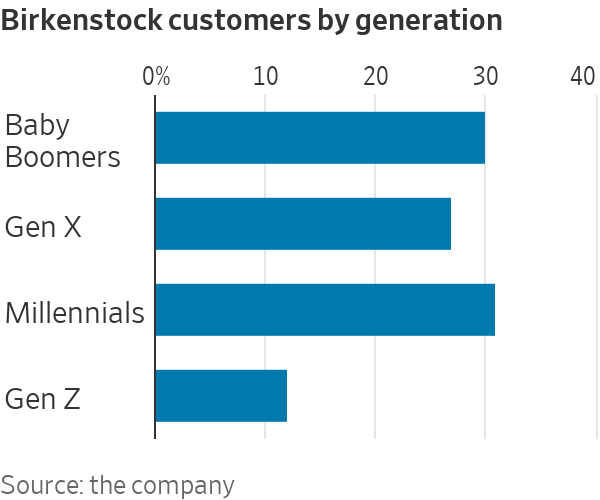

She knew they intrigued baby boomers who didn’t want to look like their mothers and fathers. As it happens, their children don’t mind looking like them. Now, boomers and millennials make up almost the exact same percentage of Birkenstock’s consumers, and the company’s Arizona sandals and Boston clogs can be found in high schools and retirement homes.

The business is also barely recognisable from when she sold Birkenstock USA to her employees and retired in 2002. It was later folded into the German parent company, which is run by Oliver Reichert, the first person outside the Birkenstock family to be the CEO. Arnault’s L Catterton invested in 2021 with eyes on this week’s IPO.

Birkenstock has expanded into sneakers, boots and sandals in wool, shearling and waterproof material. Its proudly frumpy sandals meant to free women from the norms of fashion have become posh enough for celebrities, models and collaborations with Manolo Blahnik. The people who once turned up their noses at them now put their feet in them. And the company’s dominant market is the U.S.

None of that would have been possible without Margot Fraser.

Neither would the final scene in “Barbie.”

To sell more sandals to more Americans, she was always begging her partners for more colours, so Fraser would have been delighted to see what’s on the feet of another woman named Margot.

She’s wearing a pair of pink Birkenstocks.

Copyright 2020, Dow Jones & Company, Inc. All Rights Reserved Worldwide. LEARN MORE

Copyright 2020, Dow Jones & Company, Inc. All Rights Reserved Worldwide. LEARN MORE

This stylish family home combines a classic palette and finishes with a flexible floorplan

Just 55 minutes from Sydney, make this your creative getaway located in the majestic Hawkesbury region.

Impact investing is becoming more mainstream as larger, institutional asset owners drive more money into the sector, according to the nonprofit Global Impact Investing Network in New York.

In the GIIN’s State of the Market 2024 report, published late last month, researchers found that assets allocated to impact-investing strategies by repeat survey responders grew by a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of 14% over the last five years.

These 71 responders to both the 2019 and 2024 surveys saw their total impact assets under management grow to US$249 billion this year from US$129 billion five years ago.

Medium- and large-size investors were largely responsible for the strong impact returns: Medium-size investors posted a median CAGR of 11% a year over the five-year period, and large-size investors posted a median CAGR of 14% a year.

Interestingly, the CAGR of assets held by small investors dropped by a median of 14% a year.

“When we drill down behind the compound annual growth of the assets that are being allocated to impact investing, it’s largely those larger investors that are actually driving it,” says Dean Hand, the GIIN’s chief research officer.

Overall, the GIIN surveyed 305 investors with a combined US$490 billion under management from 39 countries. Nearly three-quarters of the responders were investment managers, while 10% were foundations, and 3% were family offices. Development finance institutions, institutional asset owners, and companies represented most of the rest.

The majority of impact strategies are executed through private-equity, but public debt and equity have been the fastest-growing asset classes over the past five years, the report said. Public debt is growing at a CAGR of 32%, and public equity is growing at a CAGR of 19%. That compares to a CAGR of 17% for private equity and 7% for private debt.

According to the GIIN, the rise in public impact assets is being driven by larger investors, likely institutions.

Private equity has traditionally served as an ideal way to execute impact strategies, as it allows investors to select vehicles specifically designed to create a positive social or environmental impact by, for example, providing loans to smallholder farmers in Africa or by supporting fledging renewable energy technologies.

Future Returns: Preqin expects managers to rely on family offices, private banks, and individual investors for growth in the next six years

But today, institutional investors are looking across their portfolios—encompassing both private and public assets—to achieve their impact goals.

“Institutional asset owners are saying, ‘In the interests of our ultimate beneficiaries, we probably need to start driving these strategies across our assets,’” Hand says. Instead of carving out a dedicated impact strategy, these investors are taking “a holistic portfolio approach.”

An institutional manager may want to address issues such as climate change, healthcare costs, and local economic growth so it can support a better quality of life for its beneficiaries.

To achieve these goals, the manager could invest across a range of private debt, private equity, and real estate.

But the public markets offer opportunities, too. Using public debt, a manager could, for example, invest in green bonds, regional bank bonds, or healthcare social bonds. In public equity, it could invest in green-power storage technologies, minority-focused real-estate trusts, and in pharmaceutical and medical-care company stocks with the aim of influencing them to lower the costs of care, according to an example the GIIN lays out in a separate report on institutional strategies.

Influencing companies to act in the best interests of society and the environment is increasingly being done through such shareholder advocacy, either directly through ownership in individual stocks or through fund vehicles.

“They’re trying to move their portfolio companies to actually solving some of the challenges that exist,” Hand says.

Although the rate of growth in public strategies for impact is brisk, among survey respondents investments in public debt totaled only 12% of assets and just 7% in public equity. Private equity, however, grabs 43% of these investors’ assets.

Within private equity, Hand also discerns more evidence of maturity in the impact sector. That’s because more impact-oriented asset owners invest in mature and growth-stage companies, which are favored by larger asset owners that have more substantial assets to put to work.

The GIIN State of the Market report also found that impact asset owners are largely happy with both the financial performance and impact results of their holdings.

About three-quarters of those surveyed were seeking risk-adjusted, market-rate returns, although foundations were an exception as 68% sought below-market returns, the report said. Overall, 86% reported their investments were performing in line or above their expectations—even when their targets were not met—and 90% said the same for their impact returns.

Private-equity posted the strongest results, returning 17% on average, although that was less than the 19% targeted return. By contrast, public equity returned 11%, above a 10% target.

The fact some asset classes over performed and others underperformed, shows that “normal economic forces are at play in the market,” Hand says.

Although investors are satisfied with their impact performance, they are still dealing with a fragmented approach for measuring it, the report said. “Despite this, over two-thirds of investors are incorporating impact criteria into their investment governance documents, signalling a significant shift toward formalising impact considerations in decision-making processes,” it said.

Also, more investors are getting third-party verification of their results, which strengthens their accountability in the market.

“The satisfaction with performance is nice to see,” Hand says. “But we do need to see more about what’s happening in terms of investors being able to actually track both the impact performance in real terms as well as the financial performance in real terms.”

This stylish family home combines a classic palette and finishes with a flexible floorplan

Just 55 minutes from Sydney, make this your creative getaway located in the majestic Hawkesbury region.