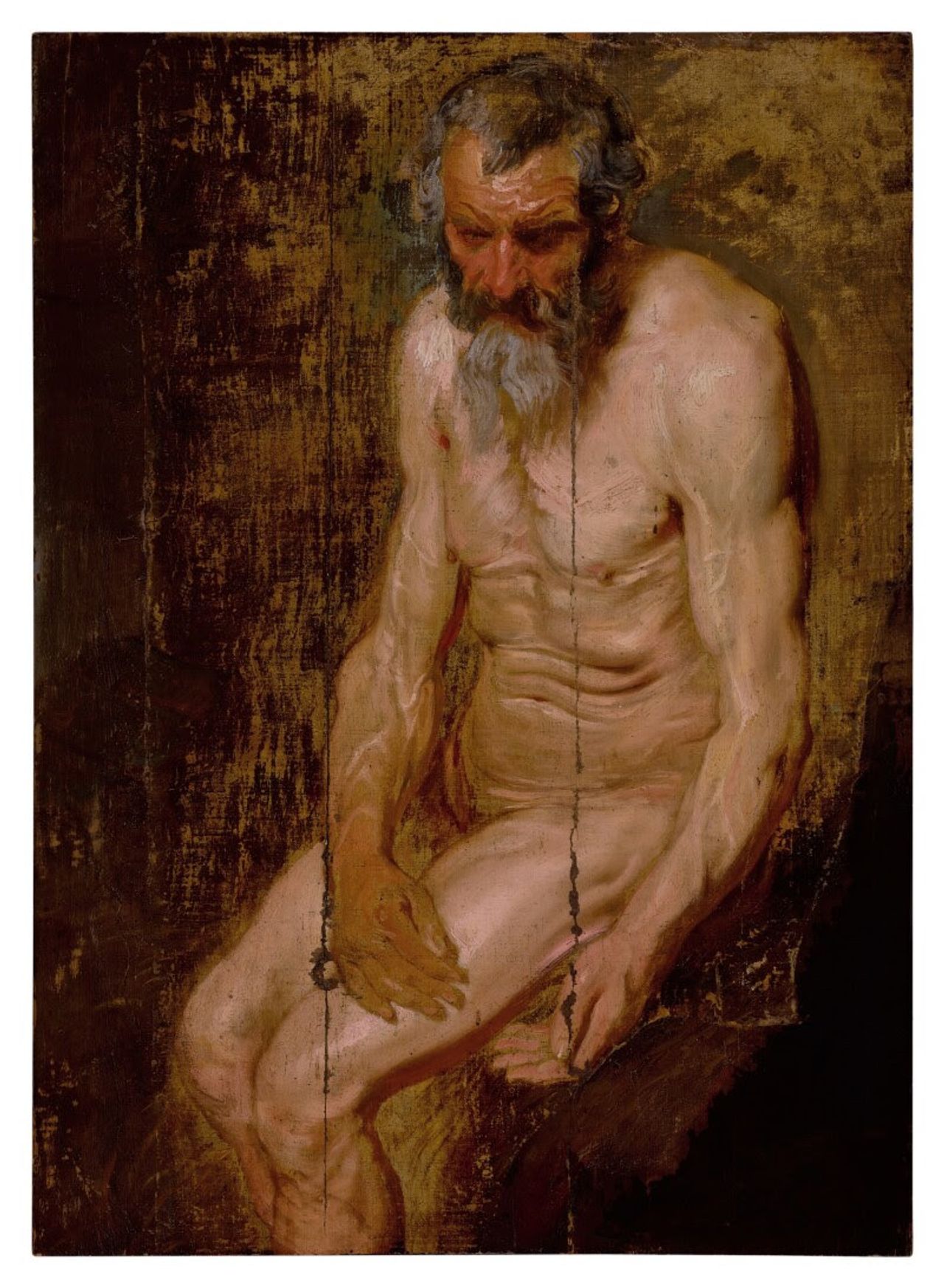

400-Year-Old Van Dyck Sketch Discovered in a New York Farm Shed Sells for $3 Million

A Sketch for Saint Jerome from 1615-18 by Anthony Van Dyck that was discovered in the late 20th century in a farm shed in Kinderhook, N.Y., fetched US$3.075 million at a Sotheby’s auction last week in New York.

Considered lost for centuries, the painting was purchased by the late collector Albert B. Roberts at an auction in 2002 for just US$600, according to Sotheby’s. Roberts then sought the help of art historian and Van Dyck scholar Susan J. Barnes, who confirmed the sketch was a “surprisingly well-preserved” work by Van Dyck.

Roberts died in August 2021 at the age of 89. A portion of proceeds from the sale will benefit his namesake foundation, which supports artists and other creatives.

“Not only is the story of its journey from a farm shed in Kinderhook to the rostrum at Sotheby’s irresistible, it is also a highly important early work by the teenage Van Dyck, completed while he was still under the tutelage of [Peter Paul] Rubens,” Christopher Apostle, Sotheby’s head of Old Master paintings in New York, said in a statement.

The auction house declined to disclose the identity of the buyer.

Last week’s Old Masters sale at Sotheby’s was headlined by a 1609 painting by Rubens, Salome, depicting the head of Saint John the Baptist. Offered from the collection of Mark Fisch, a real estate developer and a trustee of the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, and his ex-wife, Rachel Davidson, a former New Jersey judge, the masterpiece fetched US$26.9 million, the third-highest price for the artist at auction.

The 10 Baroque masterworks from Fisch Davidson collection brought in a total of US$49.6 million in a white-glove auction.

Sotheby’s Master Week sale—which is poised to break a record of US$100 million— continues throughout this week. One highlight will be a Kobe Bryant game-worn Lakers jersey, which will be offered on Wednesday with an estimate between US$5 million and US$7 million.

Copyright 2020, Dow Jones & Company, Inc. All Rights Reserved Worldwide. LEARN MORE

Copyright 2020, Dow Jones & Company, Inc. All Rights Reserved Worldwide. LEARN MORE

This stylish family home combines a classic palette and finishes with a flexible floorplan

Just 55 minutes from Sydney, make this your creative getaway located in the majestic Hawkesbury region.

Continued stagflation and cost of living pressures are causing couples to think twice about starting a family, new data has revealed, with long term impacts expected

Australia is in the midst of a ‘baby recession’ with preliminary estimates showing the number of births in 2023 fell by more than four percent to the lowest level since 2006, according to KPMG. The consultancy firm says this reflects the impact of cost-of-living pressures on the feasibility of younger Australians starting a family.

KPMG estimates that 289,100 babies were born in 2023. This compares to 300,684 babies in 2022 and 309,996 in 2021, according to the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS). KPMG urban economist Terry Rawnsley said weak economic growth often leads to a reduced number of births. In 2023, ABS data shows gross domestic product (GDP) fell to 1.5 percent. Despite the population growing by 2.5 percent in 2023, GDP on a per capita basis went into negative territory, down one percent over the 12 months.

“Birth rates provide insight into long-term population growth as well as the current confidence of Australian families,” said Mr Rawnsley. “We haven’t seen such a sharp drop in births in Australia since the period of economic stagflation in the 1970s, which coincided with the initial widespread adoption of the contraceptive pill.”

Mr Rawnsley said many Australian couples delayed starting a family while the pandemic played out in 2020. The number of births fell from 305,832 in 2019 to 294,369 in 2020. Then in 2021, strong employment and vast amounts of stimulus money, along with high household savings due to lockdowns, gave couples better financial means to have a baby. This led to a rebound in births.

However, the re-opening of the global economy in 2022 led to soaring inflation. By the start of 2023, the Australian consumer price index (CPI) had risen to its highest level since 1990 at 7.8 percent per annum. By that stage, the Reserve Bank had already commenced an aggressive rate-hiking strategy to fight inflation and had raised the cash rate every month between May and December 2022.

Five more rate hikes during 2023 put further pressure on couples with mortgages and put the brakes on family formation. “This combination of the pandemic and rapid economic changes explains the spike and subsequent sharp decline in birth rates we have observed over the past four years,” Mr Rawnsley said.

The impact of high costs of living on couples’ decision to have a baby is highlighted in births data for the capital cities. KPMG estimates there were 60,860 births in Sydney in 2023, down 8.6 percent from 2019. There were 56,270 births in Melbourne, down 7.3 percent. In Perth, there were 25,020 births, down 6 percent, while in Brisbane there were 30,250 births, down 4.3 percent. Canberra was the only capital city where there was no fall in the number of births in 2023 compared to 2019.

“CPI growth in Canberra has been slightly subdued compared to that in other major cities, and the economic outlook has remained strong,” Mr Rawnsley said. “This means families have not been hurting as much as those in other capital cities, and in turn, we’ve seen a stabilisation of births in the ACT.”

This stylish family home combines a classic palette and finishes with a flexible floorplan

Just 55 minutes from Sydney, make this your creative getaway located in the majestic Hawkesbury region.