The Sandwich Generation Is Stressed Out, Low on Money and Short on Time

As millennials start to hit middle age—and boomers near their 80s—the number of Americans caring for both older and younger generations is poised to surge

At 34, Kait Giordano is juggling her job, a newborn and two parents with dementia.

Just over a month into motherhood, she tends to her infant son and her live-in parents in the morning and afternoon, some days with the help of a rotating cast of paid companions at their Tucker, Ga., home. In the evenings, her husband, Tamrin, takes over while she colours hair.

They had already delayed starting a family when Kait’s father moved in a few years ago. Her mother moved in this year. “We chose to take this on,” she says. “We didn’t want to wait any longer.”

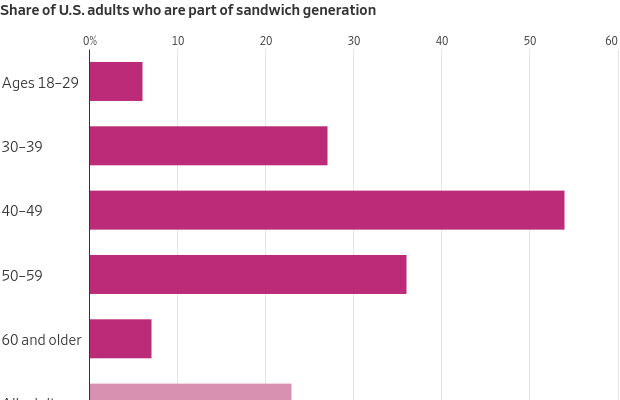

More Americans shoulder a double load of caring for their children and at least one adult , often a parent. The “sandwich generation” has grown to at least 11 million in the U.S., according to one estimate, and shifts in demographics, costs and work are making it a longer and tougher slog.

People are having children later, and they are living longer , often with care-intensive conditions such as dementia. That means many are taking care of elderly parents when their own kids are still young and require more intensive parenting—and for longer stretches of their lives than previous generations of sandwiched caregivers.

As the oldest millennials start to hit middle age —and baby boomers near their 80s—the number of Americans caring for older and younger family makes up a significant part of the electorate. Vice President Kamala Harris invoked the sandwich generation when she recently proposed expanding Medicare benefits to cover home healthcare.

“There are so many people in our country who are right in the middle,” the Democratic presidential candidate said on ABC’s “The View” this month. “It’s just almost impossible to do it all, especially if they work.”

Responding to the Harris proposal, former President Donald Trump ’s campaign said he would give priority to home-care benefits by shifting resources to at-home senior care and provide tax credits to support unpaid family caregivers.

The growing burden on this sandwich generation weakens careers and quality of life, and has ramifications for society at large. It is a drag on monthly budgets and long-term financial health.

A 40-something contributing $1,500 a month over five years to support an aging parent stands to lose more than $1 million in retirement savings, according to an analysis by Steph Wagner , national director of women and wealth at Northern Trust Wealth Management.

“It’s become incredibly expensive to manage the longevity that we’ve created,” says Bradley Schurman , an author and demographic strategist, who says that the demands of caring for older generations could push more people in midlife to retreat from the workforce, particularly women. “That’s a massive risk for the U.S. economy.”

Career goals on hold

Not too long ago, the typical sandwich caregiver was a woman in her late 40s with teenage kids and maybe a part-time job. Now, according to a 2023 AARP report, the average age of these caregivers is 44, and a growing share are men. Nearly a third are millennials and Gen Z. They are in the critical early-to-middle stages of their careers and three-quarters of them work full or part time.

Diana Fuller, 49, says being the go-to person for her 83-year-old mother’s care for more than four years has been stressful, even with her mother now living in a nearby, $10,000-a month memory-care centre in Charlotte., N.C. (Long-term-care insurance covers 75%; the rest is paid out of her mother’s savings.)

She has put on the back burner career goals such as ramping up the leg warmer business she started with her sister. She has missed moments such as her 9-year-old son’s school holiday concert last year because of her mother’s frequent hospital stays.

Her husband picks up a lot of the child care duties when her mom is in the hospital. Still, she says, “it often feels like everything is about to implode.”

The financial pressures are also growing for the sandwich generation. According to a Care.com survey of 2,000 parents, 60% of U.S. families spent 20% or more of their annual household income on child care last year, up from 51% of families in 2021. Meanwhile, the median cost of a home health aide climbed 10% last year to $75,500, data from long-term-care insurer Genworth Financial show.

Caregivers often risk paying for such costs in their own old age, financial advisers say. More than half reported in a 2023 New York Life survey that they had made a sacrifice to their own financial security to provide care for their parents on top of their children.

Long-distance care

Many in the sandwich generation say they feel torn between the needs of their kids and parents. Liam Davitt , a public-relations professional, and his wife, Lisa Fels Davitt , recently moved from their Washington, D.C., condo to suburban New Jersey so that their 7-year-old son could be closer to cousins and go to a good public school. (They had previously paid for private school.)

That meant moving away from his 84-year-old mother in an independent living community. The long distance has made helping her even with little things more complicated, such as troubleshooting glitches with her iPhone. He recently enlisted a nearby fraternity brother to help her assemble a new walker.

An avid runner, he says he finds himself taking care of himself—avoiding potentially ankle-twisting mud runs and keeping up with his doctors’ appointments, for example—out of fear he won’t be able to care for his younger and older family.

“If all of a sudden I’m less mobile, then I’m more of a burden on my own family” says Davitt. He is planning to move his mother closer by.

The Giordanos, in Georgia, have made adjustments, too. With their newborn keeping them busy, they installed cameras and door chimes to help monitor Kait’s parents.

Her parents enjoy pushing their grandson in the stroller around the house while supervised, she says. When Tamrin comes home from work, he gives his in-laws dinner and medications while holding the baby.

The couple isn’t sure when they’ll have another child, which would require paying for more help.

“We may have to wait,” Kait said. “We’re very much living in the moment.”

Copyright 2020, Dow Jones & Company, Inc. All Rights Reserved Worldwide. LEARN MORE

Copyright 2020, Dow Jones & Company, Inc. All Rights Reserved Worldwide. LEARN MORE

A long-standing cultural cruise and a new expedition-style offering will soon operate side by side in French Polynesia.

The pandemic-fuelled love affair with casual footwear is fading, with Bank of America warning the downturn shows no sign of easing.

The pandemic-fuelled love affair with casual footwear is fading, with Bank of America warning the downturn shows no sign of easing.

The boom in casual footware ushered in by the pandemic has ended, a potential problem for companies such as Adidas that benefited from the shift to less formal clothing, Bank of America says.

The casual footwear business has been on the ropes since mid-2023 as people began returning to office.

Analyst Thierry Cota wrote that while most downcycles have lasted one to two years over the past two decades or so, the current one is different.

It “shows no sign of abating” and there is “no turning point in sight,” he said.

Adidas and Nike alone account for almost 60% of revenue in the casual footwear industry, Cota estimated, so the sector’s slower growth could be especially painful for them as opposed to brands that have a stronger performance-shoe segment. Adidas may just have it worse than Nike.

Cota downgraded Adidas stock to Underperform from Buy on Tuesday and slashed his target for the stock price to €160 (about $187) from €213. He doesn’t have a rating for Nike stock.

Shares of Adidas listed on the German stock exchange fell 4.5% Tuesday to €162.25. Nike stock was down 1.2%.

Adidas didn’t immediately respond to a request for comment.

Cota sees trouble for Adidas both in the short and long term.

Adidas’ lifestyle segment, which includes the Gazelles and Sambas brands, has been one of the company’s fastest-growing business, but there are signs growth is waning.

Lifestyle sales increased at a 10% annual pace in Adidas’ third quarter, down from 13% in the second quarter.

The analyst now predicts Adidas’ organic sales will grow by a 5% annual rate starting in 2027, down from his prior forecast of 7.5%.

The slower revenue growth will likewise weigh on profitability, Cota said, predicting that margins on earnings before interest and taxes will decline back toward the company’s long-term average after several quarters of outperforming. That could result in a cut to earnings per share.

Adidas stock had a rough 2025. Shares shed 33% in the past 12 months, weighed down by investor concerns over how tariffs, slowing demand, and increased competition would affect revenue growth.

Nike stock fell 9% throughout the period, reflecting both the company’s struggles with demand and optimism over a turnaround plan CEO Elliott Hill rolled out in late 2024.

Investors’ confidence has faded following Nike’s December earnings report, which suggested that a sustained recovery is still several quarters away. Just how many remains anyone’s guess.

But if Adidas’ challenges continue, as Cota believes they will, it could open up some space for Nike to claw back any market share it lost to its rival.

Investors should keep in mind, however, that the field has grown increasingly crowded in the past five years. Upstarts such as On Holding and Hoka also present a formidable challenge to the sector’s legacy brands.

Shares of On and Deckers Outdoor , Hoka’s parent company, fell 11% and 48%, respectively, in 2025, but analysts are upbeat about both companies’ fundamentals as the new year begins.

The battle of the sneakers is just getting started.

Australia’s market is on the move again, and not always where you’d expect. We’ve found the surprise suburbs where prices are climbing fastest.

The megamansion was built for Tony Pritzker, heir to the Hyatt Hotel fortune and brother of Illinois Gov. JB Pritzker.