The Disappearing White-Collar Job

A once-in-a-generation convergence of technology and pressure to operate more efficiently has corporations saying many lost jobs may never return

For generations of Americans, a corporate job was a path to stable prosperity. No more.

The jobs lost in a months long cascade of white-collar layoffs triggered by over hiring and rising interest rates might never return, corporate executives and economists say. Companies are rethinking the value of many white-collar roles, in what some experts anticipate will be a permanent shift in labor demand that will disrupt the work life of millions of Americans whose jobs will be lost, diminished or revamped partly through the use of artificial intelligence.

“We may be at the peak of the need for knowledge workers,” said Atif Rafiq, a former chief digital officer at McDonald’s and Volvo. “We just need fewer people to do the same thing.”

Long after robots began taking manufacturing jobs, artificial intelligence is now coming for the higher-ups—accountants, software programmers, human-resources specialists and lawyers—and converging with unyielding pressure on companies to operate more efficiently.

Meta Platforms CEO Mark Zuckerberg told employees after the Facebook parent’s latest round of layoffs that many jobs aren’t coming back because new technologies will allow the company to operate more efficiently. International Business Machines CEO Arvind Krishna recently said the company could pause some hiring to see what kind of back-office work can be done with AI. Leaders in many industries say they expect the new technology will augment some existing roles, changing what people do on the job. AI could allow employees to better contribute to their companies by doing more meaningful work, said Mr. Rafiq, author of a new book on management.

For the year ended in March, the number of unemployed white-collar workers rose by roughly 150,000, according to an analysis from Employ America, a nonpartisan research group. That included workers in professional services, management, computer occupations, engineering, and scientists.

“I can’t think of any job where it’s like AI by itself,” said Rodney McMullen, chief executive of grocery chain Kroger, which has about 430,000 employees. “I can think of a lot of jobs that are being affected by AI.”

That underlying dynamic has been accelerated by the binge hiring of recent years. Company leaders say they have become saddled with bloated managerial layers that slow decision making. The retailer Gap said in April that its new round of corporate job cuts would trim what has become an inefficient corporate bureaucracy.

Lyft’s new CEO, David Risher, told investors this month that the ride-sharing company had cut the number of management layers from eight to five. Lyft said in April it would eliminate roughly 1,000 white-collar jobs in its latest round of layoffs. The flattened corporate structure means that Lyft “can innovate faster,” Mr. Risher said.

Jobs go through boom-and-bust cycles. In previous downturns, executives pledged to make streamlining efforts stick, only to replenish or grow their corporate ranks when business conditions improved. Many executives say the forces now at play suggest this time is different.

During past periods when higher interest rates pitched the U.S. economy into recession, job losses were often led by industries most sensitive to rate changes, such as manufacturing and construction. “It seems like we’re not seeing that right now. It could be the structure of the economy has changed,” said Preston Mui, an economist at Employ America, who has been studying white-collar job losses.

“A real question is: The Fed raises rates and softens the economy, where is that going to show up?” he said. The evidence is pointing to white-collar jobs, he said.

After 14 months of interest-rate increases by the Federal Reserve, job openings dropped to their lowest level in nearly two years in March, the most recent month of Labor Department data. Layoffs in the information sector were up 88% in March from a year earlier and up 55% in finance and insurance, the data show. For manufacturing, they were up 25% over the same period.

Companies are for the moment focused on keeping blue-collar employees—restaurant servers, warehouse workers, drivers and the like—who remain in short supply, according to economists and human-resources specialists. For C-suite executives under pressure from investors, that exposes middle managers and other white-collar workers to layoffs.

Whole Foods and Walt Disney announced layoffs in recent weeks that largely hit corporate staff while sparing such customer-service jobs as grocery clerk and hourly theme-park attendant. Retail workers, including salespeople and cashiers, were among the most in-demand roles in the first quarter of the year, according to the jobs site LinkedIn, along with nurses and drivers.

“Companies realise they over-hired in the middle,” said Nick Bunker, an economist at jobs site Indeed. “They’re paring things back.”

The number of employees working and the number of hours they worked in white-collar sectors such as professional services and medical and veterinary roles contracted in late April compared with January, according to data from Homebase, which provides software services to small businesses for scheduling hourly workers.

Sudden fall

Colton Pace, chief executive of Ownwell, a property-tax analysis company based in Austin, Texas, said he was filling more open roles with temporary contractors to give the startup flexibility in an uncertain economy. He also sees technology soon doing more company tasks.

“I want to be a little more cautious in how we hire,” Mr. Pace said. “In addition to that, it makes more sense because we’re not sure. Some of these roles will be automated away.”

A year ago, roughly 15% of the company was made up of contractors or seasonal workers. Those workers now make up a quarter of Ownwell’s roughly 85-person workforce. Mr. Pace said he could see AI and other tools eventually shouldering a greater share of the work in customer support, operations and sales.

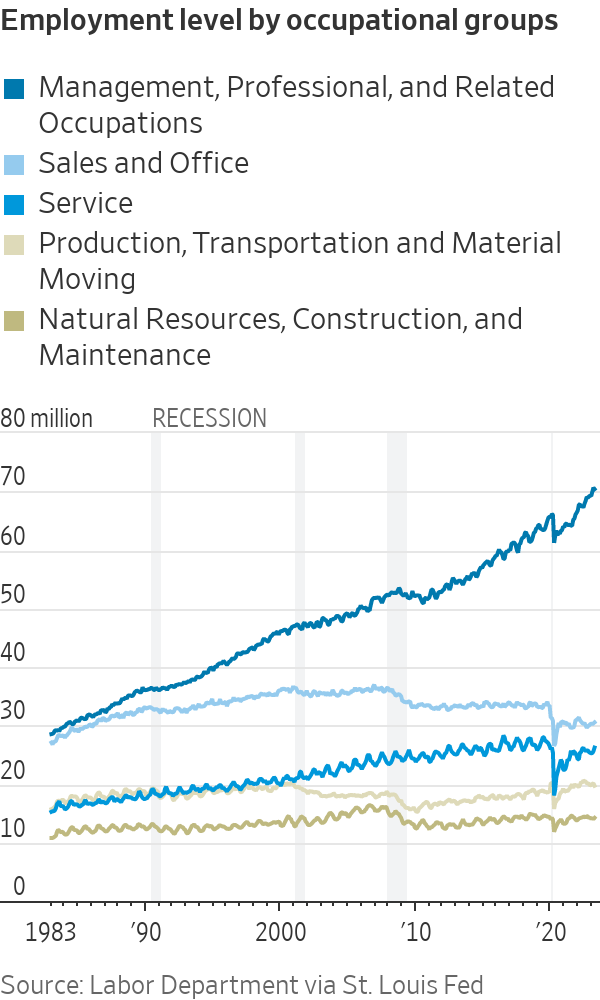

There is no firm definition of white-collar employee in government data. The term broadly applies to people who work in offices and have higher education, such as a bachelor’s degree or some college. In recent decades, hiring in management and professional jobs rapidly outpaced other categories. The number of employees in management and professional occupations increased nearly 150% in the past 40 years, and nearly 36% since the end of the 2007-09 recession, according to Labor Department data. By comparison, service occupations such as barbers, child care workers and casino employees have risen 72% since 1983, the earliest available data, and 3.5% since June 2009.

Over the years, higher demand for skilled workers and higher pay for college-educated workers widened the economic gap with blue-collar workers. Yet following the height of the Covid-19 pandemic, wages rose fastest among low-earners, reducing the college wage premium and reversing about a quarter of the rise in wage inequality since 1980, according to a study by economists including David Autor of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

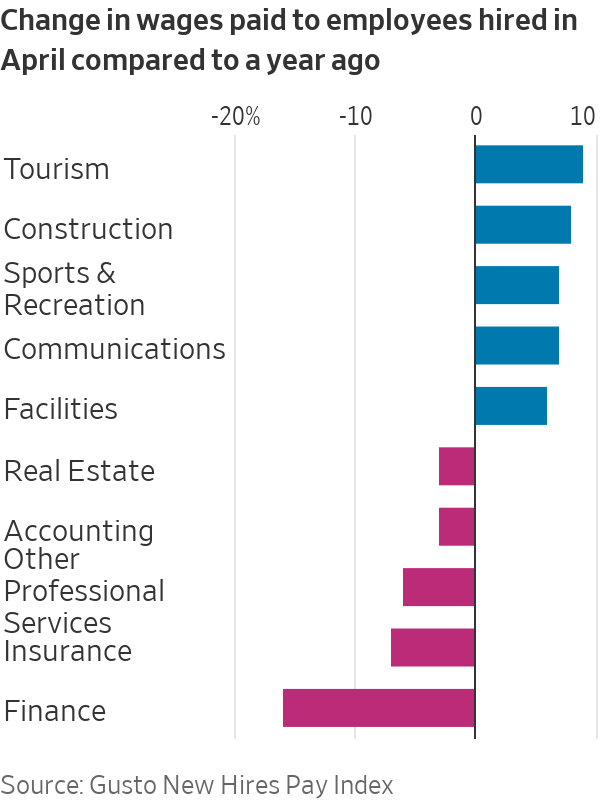

Payroll data from more than 300,000 small- and medium-size businesses showed that wages for new hires had generally declined in April from a year ago but fell most rapidly in white-collar professions, such as finance and insurance, according to Gusto, a payroll, benefits and human-resource management software maker. They rose most quickly in such services and blue-collar industries as tourism, construction and recreation, Gusto found.

Digital smarts

As companies look to cut costs, some employers have said middle managers will have to give up their teams and return to being just another worker. Others, including McDonald’s, have asked staffers to accept reduced compensation if they want to stay at the company.

Artificial intelligence also is expected to eliminate some positions entirely. Mr. Krishna, of IBM, has said in recent weeks that he could see 30% of IBM’s roughly 26,000 non-customer-facing roles being replaced by automation or AI over a five-year period.

An IBM spokesman said the company was still hiring for thousands of positions. “There is no blanket hiring ‘pause’ in place,” he said. “IBM is being deliberate and thoughtful in our hiring.”

The Labor Department projects that of the 20 occupations that will create the most jobs through 2031, about two-thirds will be blue-collar jobs that pay around $32,000 a year, including home-health and personal-care aides, restaurant cooks, fast-food workers, wait staff and freight movers.

The professions with the best prospects for growth that require a college degree include software developers, operations managers and registered nurses. Those jobs pay around $100,000 a year and are forecast to be better protected than other white-collar work from AI displacement.

Some employers are already figuring out exactly how many fewer white-collar workers they will need in the future. The business- and government-consulting firm Guidehouse in McLean, Va., which employs about 16,500 people, had expected to triple its head count in the coming years to reach its goal of roughly tripling its revenue to $10 billion, said CEO Scott McIntyre. Not anymore, he said.

Mr. McIntyre expects that with the help of AI and increased automation, Guidehouse may need to hire 40,000 people instead of 50,000 to reach its growth target. “The smarter you are with enabling technology and technology that creates productivity, the smarter you can be about hiring,” he said.

Copyright 2020, Dow Jones & Company, Inc. All Rights Reserved Worldwide. LEARN MORE

Copyright 2020, Dow Jones & Company, Inc. All Rights Reserved Worldwide. LEARN MORE

Pure Amazon has begun journeys deep into Peru’s Pacaya-Samiria National Reserve, combining contemporary design, Indigenous craftsmanship and intimate wildlife encounters in one of the richest ecosystems on Earth.

Australia’s housing market defies forecasts as prices surge past pandemic-era benchmarks.

Selloff in bitcoin and other digital tokens hits crypto-treasury companies.

The hottest crypto trade has turned cold. Some investors are saying “told you so,” while others are doubling down.

It was the move to make for much of the year: Sell shares or borrow money, then plough the cash into bitcoin, ether and other cryptocurrencies. Investors bid up shares of these “crypto-treasury” companies, seeing them as a way to turbocharge wagers on the volatile crypto market.

Michael Saylor pioneered the move in 2020 when he transformed a tiny software company, then called MicroStrategy , into a bitcoin whale now known as Strategy. But with bitcoin and ether prices now tumbling, so are shares in Strategy and its copycats. Strategy was worth around $128 billion at its peak in July; it is now worth about $70 billion.

The selloff is hitting big-name investors, including Peter Thiel, the famed venture capitalist who has backed multiple crypto-treasury companies, as well as individuals who followed evangelists into these stocks.

Saylor, for his part, has remained characteristically bullish, taking to social media to declare that bitcoin is on sale. Sceptics have been anticipating the pullback, given that crypto treasuries often trade at a premium to the underlying value of the tokens they hold.

“The whole concept makes no sense to me. You are just paying $2 for a one-dollar bill,” said Brent Donnelly, president of Spectra Markets. “Eventually those premiums will compress.”

When they first appeared, crypto-treasury companies also gave institutional investors who previously couldn’t easily access crypto a way to invest. Crypto exchange-traded funds that became available over the past two years now offer the same solution.

BitMine Immersion Technologies , a big ether-treasury company backed by Thiel and run by veteran Wall Street strategist Tom Lee , is down more than 30% over the past month.

ETHZilla , which transformed itself from a biotech company to an ether treasury and counts Thiel as an investor, is down 23% in a month.

Crypto prices rallied for much of the year, driven by the crypto-friendly Trump administration. The frenzy around crypto treasuries further boosted token prices. But the bullish run abruptly ended on Oct. 10, when President Trump’s surprise tariff announcement against China triggered a selloff.

A record-long government shutdown and uncertainty surrounding Federal Reserve monetary policy also have weighed on prices.

Bitcoin prices have fallen 15% in the past month. Strategy is off 26% over that same period, while Matthew Tuttle’s related ETF—MSTU—which aims for a return that is twice that of Strategy, has fallen 50%.

“Digital asset treasury companies are basically leveraged crypto assets, so when crypto falls, they will fall more,” Tuttle said. “Bitcoin has shown that it’s not going anywhere and that you get rewarded for buying the dips.”

At least one big-name investor is adjusting his portfolio after the tumble of these shares. Jim Chanos , who closed his hedge funds in 2023 but still trades his own money and advises clients, had been shorting Strategy and buying bitcoin, arguing that it made little sense for investors to pay up for Saylor’s company when they can buy bitcoin on their own. On Friday, he told clients it was time to unwind that trade.

Crypto-treasury stocks remain overpriced, he said in an interview on Sunday, partly because their shares retain a higher value than the crypto these companies hold, but the levels are no longer exorbitant. “The thesis has largely played out,” he wrote to clients.

Many of the companies that raised cash to buy cryptocurrencies are unlikely to face short-term crises as long as their crypto holdings retain value. Some have raised so much money that they are still sitting on a lot of cash they can use to buy crypto at lower prices or even acquire rivals.

But companies facing losses will find it challenging to sell new shares to buy more cryptocurrencies, analysts say, potentially putting pressure on crypto prices while raising questions about the business models of these companies.

“A lot of them are stuck,” said Matt Cole, the chief executive officer of Strive, a bitcoin-treasury company. Strive raised money earlier this year to buy bitcoin at an average price more than 10% above its current level.

Strive’s shares have tumbled 28% in the past month. He said Strive is well-positioned to “ride out the volatility” because it recently raised money with preferred shares instead of debt.

Cole Grinde, a 29-year-old investor in Seattle, purchased about $100,000 worth of BitMine at about $45 a share when it started stockpiling ether earlier this year. He has lost about $10,000 on the investment so far.

Nonetheless, Grinde, a beverage-industry salesman, says he’s increasing his stake. He sells BitMine options to help offset losses. He attributes his conviction in the company to the growing popularity of the Ethereum blockchain—the network that issues the ether token—and Lee’s influence.

“I think his network and his pizzazz have helped the stock skyrocket since he took over,” he said of Lee, who spent 15 years at JPMorgan Chase, is a managing partner at Fundstrat Global Advisors and a frequent business-television commentator.

An opulent Ryde home, packed with cinema, pool, sauna and more, is hitting the auction block with a $1 reserve.

On October 2, acclaimed chef Dan Arnold will host an exclusive evening, unveiling a Michelin-inspired menu in a rare masterclass of food, storytelling and flavour.