China Is Pressing Women to Have More Babies. Many Are Saying No.

The population, now around 1.4 billion, is likely to drop to around half a billion by 2100—and women are being blamed

Chinese women have had it. Their response to Beijing’s demands for more children? No.

Fed up with government harassment and wary of the sacrifices of child-rearing, many young women are putting themselves ahead of what Beijing and their families want. Their refusal has set off a crisis for the Communist Party, which desperately needs more babies to rejuvenate China’s ageing population.

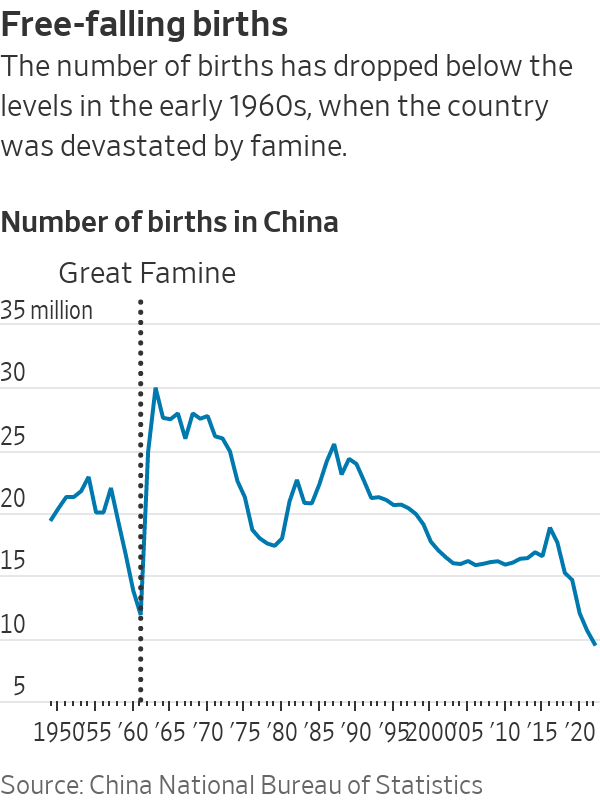

With the number of babies in free fall—fewer than 10 million were born in 2022, compared with around 16 million in 2012—China is headed toward a demographic collapse. China’s population, now around 1.4 billion, is likely to drop to just around half a billion by 2100, according to some projections. Women are taking the blame.

In October, Chinese Leader Xi Jinping urged the state-backed All-China Women’s Federation to “prevent and resolve risks in the women’s field,” according to an official account of the speech.

“It’s clear that he was not talking about risks faced by women but considering women as a major threat to social stability,” said Clyde Yicheng Wang, an assistant professor of politics at Washington and Lee University who studies Chinese government propaganda.

The State Council, China’s top government body, didn’t respond to questions about Beijing’s population policies.

Party lectures on “family values” are having little effect, even in rural parts of China.

Outside a mall in Quanjiao, a county in Anhui province, He Yanjing, a mother of two, said she has gotten several calls from community officials to encourage her to have a third child. She has no such plans. The preschool her son attended cut the number of classrooms in half because there aren’t enough children to fill them, she said.

Her friend, Feng Chenchen, the mother of a 3-year-old girl, said relatives are pressuring her to have more children, hoping she has a baby boy.

“Having had one child, I think I’ve done my duty,” Feng said. A second child, she said, would be too expensive. She said she tells relatives, “I can have another kid as long as you give me 300,000 yuan,” around $41,000.

Many young people in China, disheartened by a weak economy and high unemployment, seek alternatives to their parents’ lives. Many women view the prescribed formula of marriage and children as a raw deal.

Molly Chen, 28 years old, said the demands of caring for ageing relatives and her job as an exhibition designer in Shenzhen leave no room for kids or a husband. All she wants to do in her free moments is read or scroll through pet videos.

Chen followed the story of Su Min, a retiree who video-blogged about her solo road trip around China to escape a bad marriage. Chen said that the story, as well as online videos that women post about their lives, have deepened her impression that many men choose wives mostly as caretakers—for children, husbands and both sets of aging parents.

She lamented that she doesn’t have time even for a pet. “I can’t afford to take care of anything else outside of my parents and work,” Chen said.

Shrinkage

When Beijing said it would abolish its 35-year-old one-child policy in 2015, officials expected a baby boom. Instead, they got a baby bust.

New maternity wards were built only to close a few years later. Sales of baby-care products, including formula and diapers, have dropped. Businesses that focused on babies now target seniors.

New preschools built to make child-rearing more affordable struggle to fill classrooms and many have closed. In 2022, the number of preschools in China fell 2%, the first decline in 15 years.

Demographers and researchers predict that data will show Chinese births dipping below 9 million in 2023. The United Nations forecasts 23 million births in India, which in 2023 passed China as the world’s most populous country. The U.S. will have around 3.7 million babies born in 2023, the U.N. estimated.

The one-child policy brought much of China’s demographic gloom: There are fewer young people than in the past, including millions fewer women of childbearing age every year. Those women are increasingly reluctant to marry and have children, accelerating the population decline.

In China, 6.8 million couples registered marriages in 2022, compared with 13 million in 2013. The country’s total fertility rate in 2022—the average number of babies a woman has in her lifetime—is approaching one birth per woman, or 1.09. In 2020, it was 1.30, well below the 2.1 needed to keep a population stable.

The campaign for a “birth-friendly culture” has taken on the tone of an urgent national mission, with government-organised matchmaking events and a program encouraging military families to have more babies.

“Soldiers win battles. When it comes to giving birth to second or third children and implementing the national fertility policy, we are also taking the lead and charging to the front,” Zeng Jian, a top obstetrician-gynaecologist at a military hospital in Tianjin, told state media in 2022.

In August, residents of the western city of Xi’an said they received an automated greeting from a government number during the Qixi Festival, the Chinese equivalent of Valentine’s Day: “Wishing you sweet love and marriage at an appropriate age. Let’s extend the Chinese bloodline.”

The message drew a backlash on social media. “My mother-in-law doesn’t even push me to have a second child,” one person wrote. “I guess next, arranged marriages will come back,” another commented.

Beijing leans more to encouragement than the kind of coercion that marked the one-child policy. Local governments offer cash incentives for couples having a second or third child. A county in Zhejiang province gives a $137 cash bonus to every couple getting married before age 25.

In 2021, the city of Luanzhou asked unmarried people to sign up for a government-sponsored dating initiative that uses big data to find matches citywide. A district in the city of Handan provides a one-stop wedding-planning service.

Hide and seek

The shift means some women have gone from trying to dodge punishment for having too many children to being hounded to have more.

A decade ago, a woman surnamed Zhang was in a cat-and-mouse game with authorities after she decided to have a second child. She asked that her first name not be used.

While pregnant, she left her job to stay out of public view, fearful officials would pressure her to have an abortion, she said. After giving birth, in 2014, she stayed with relatives for a year. When she returned home, local family-planning officials fined her and her husband around $10,000. She said she was forced to have an intrauterine device implanted to prevent pregnancy. Authorities required her to have it checked every three months.

Months later, the Chinese government announced the one-child policy would be scrapped. For a while, authorities still demanded Zhang have her IUD checked.

She now gets text messages from officials encouraging her to have more children. She deletes them in anger. “I wish they would stop tossing us around,” she said, “and leave us ordinary people alone.”

There has been a tightening of licenses for clinics offering medical procedures to block pregnancies. In 1991, the height of the one-child policy, 6 million tubal ligations and 2 million vasectomies were performed. In 2020, there were 190,000 tubal ligations and 2,600 vasectomies.

On social media, people complain that getting a vasectomy appointment is as difficult as winning the lottery.

Officials have also tried to dial back abortions, a key tool for officials during the one-child policy. They have fallen by more than a third—from more than 14 million in 1991 to just under 9 million in 2020. China has since stopped releasing data on vasectomies, tubal ligations and abortions.

Pressurised populace

Wang Feng, a sociology professor at the University of California, Irvine, said there have been two conflicting shifts in Chinese society: a rising awareness of women’s rights and increasingly patriarchal policies.

For the first time in a quarter-century, no women are among the top two dozen officials on the Politburo. Since Xi took power in 2012, China has fallen 38 places in the World Economic Forum’s Global Gender Gap Report to No. 107 in the 2023 ranking of 146 nations.

In the Mao era, the party promised to end Confucian traditions that discriminated against women. Xi has instead stressed Confucian values, including the filial duty to have children. Families also pressure women into traditional roles.

Sophy Ouyang, 40, has known since middle school she didn’t want to marry and have children. Ouyang studied computer science, one of the few women in her village to pursue advanced schooling, and works as a software engineer in Canada.

Ouyang said that throughout her 20s, her family leaned on her to marry. Her mother said that if she had known Ouyang wouldn’t have children, she would have stopped her from getting a higher education.

Ouyang cut off contact with her family more than a decade ago. She has blocked her parents, aunts and uncles on social-media apps. “If I’m a bit more gentle with them,” she said, “they will take advantage.”

The Chinese government, which sees feminism as a nefarious ideology backed by foreign forces, has detained women’s-rights activists and erased their social-media accounts in a years long crackdown.

Even so, women have become more vocal online about their experiences relating to relationships, families and work. Their posts show a personal form of feminism that is harder for authorities to police.

Simona Dai, 31, started a podcast entitled “Oh! Mama” about birth and marriage after she learned that her mother had an abortion when she was eight-and-a-half months pregnant with a girl in the early 1990s.

Dai got married when she was 26 and said she had to endure her husband’s chauvinistic views, especially during the pandemic, when they argued about household chores. She became adamant about not having children, despite pressure from the couple’s families.

She has since applied to end her marriage. “If I didn’t divorce, I might have to have a baby,” she said.

A national debate over the treatment of women erupted in early 2022, when the video of a woman—a mother of eight, kept in a shed with a chain around her neck—sparked a social-media storm. The woman’s plight resonated with Chinese women who saw a connection to their own roles.

In recent years, Beijing has raised its guard against similar instances of social-media outrage.

A woman who worked at a branch of the All-China Women’s Federation in Guangzhou from 2020 to 2021 said the branch focused on preventing gender-related topics from going viral. She said it paid more to a tech company to police social-media comments than its budget for women’s advocacy.

During training, she said, employees were warned of serious repercussions if women’s issues in Guangzhou drew unwanted social-media attention. The women’s federation didn’t respond to requests for comment.

China’s cyberspace watchdog, which polices material seen as harmful to Chinese internet users, said in December that it was targeting content “spreading wrong views on marriage.”

Some women who decided years ago against marriage and children consider themselves lucky.

Ouyang, the software engineer in Canada, said, “I feel like I’ve completely dodged a bullet.”

—Jonathan Cheng and Grace Zhu contributed to this article.

Copyright 2020, Dow Jones & Company, Inc. All Rights Reserved Worldwide. LEARN MORE

Copyright 2020, Dow Jones & Company, Inc. All Rights Reserved Worldwide. LEARN MORE

This stylish family home combines a classic palette and finishes with a flexible floorplan

Just 55 minutes from Sydney, make this your creative getaway located in the majestic Hawkesbury region.

When will Berkshire Hathaway stop selling Bank of America stock?

Berkshire began liquidating its big stake in the banking company in mid-July—and has already unloaded about 15% of its interest. The selling has been fairly aggressive and has totaled about $6 billion. (Berkshire still holds 883 million shares, an 11.3% interest worth $35 billion based on its most recent filing on Aug. 30.)

The selling has prompted speculation about when CEO Warren Buffett, who oversees Berkshire’s $300 billion equity portfolio, will stop. The sales have depressed Bank of America stock, which has underperformed peers since Berkshire began its sell program. The stock closed down 0.9% Thursday at $40.14.

It’s possible that Berkshire will stop selling when the stake drops to 700 million shares. Taxes and history would be the reasons why.

Berkshire accumulated its Bank of America stake in two stages—and at vastly different prices. Berkshire’s initial stake came in 2017 , when it swapped $5 billion of Bank of America preferred stock for 700 million shares of common stock via warrants it received as part of the original preferred investment in 2011.

Berkshire got a sweet deal in that 2011 transaction. At the time, Bank of America was looking for a Buffett imprimatur—and the bank’s stock price was weak and under $10 a share.

Berkshire paid about $7 a share for that initial stake of 700 million common shares. The rest of the Berkshire stake, more than 300 million shares, was mostly purchased in 2018 at around $30 a share.

With Bank of America stock currently trading around $40, Berkshire faces a high tax burden from selling shares from the original stake of 700 million shares, given the low cost basis, and a much lighter tax hit from unloading the rest. Berkshire is subject to corporate taxes—an estimated 25% including local taxes—on gains on any sales of stock. The tax bite is stark.

Berkshire might own $2 to $3 a share in taxes on sales of high-cost stock and $8 a share on low-cost stock purchased for $7 a share.

New York tax expert Robert Willens says corporations, like individuals, can specify the particular lots when they sell stock with multiple cost levels.

“If stock is held in the custody of a broker, an adequate identification is made if the taxpayer specifies to the broker having custody of the stock the particular stock to be sold and, within a reasonable time thereafter, confirmation of such specification is set forth in a written document from the broker,” Willens told Barron’s in an email.

He assumes that Berkshire will identify the high-cost Bank of America stock for the recent sales to minimize its tax liability.

If sellers don’t specify, they generally are subject to “first in, first out,” or FIFO, accounting, meaning that the stock bought first would be subject to any tax on gains.

Buffett tends to be tax-averse—and that may prompt him to keep the original stake of 700 million shares. He could also mull any loyalty he may feel toward Bank of America CEO Brian Moynihan , whom Buffett has praised in the past.

Another reason for Berkshire to hold Bank of America is that it’s the company’s only big equity holding among traditional banks after selling shares of U.S. Bancorp , Bank of New York Mellon , JPMorgan Chase , and Wells Fargo in recent years.

Buffett, however, often eliminates stock holdings after he begins selling them down, as he did with the other bank stocks. Berkshire does retain a smaller stake of about $3 billion in Citigroup.

There could be a new filing on sales of Bank of America stock by Berkshire on Thursday evening. It has been three business days since the last one.

Berkshire must file within two business days of any sales of Bank of America stock since it owns more than 10%. The conglomerate will need to get its stake under about 777 million shares, about 100 million below the current level, before it can avoid the two-day filing rule.

It should be said that taxes haven’t deterred Buffett from selling over half of Berkshire’s stake in Apple this year—an estimated $85 billion or more of stock. Barron’s has estimated that Berkshire may owe $15 billion on the bulk of the sales that occurred in the second quarter.

Berkshire now holds 400 million shares of Apple and Barron’s has argued that Buffett may be finished reducing the Apple stake at that round number, which is the same number of shares that Berkshire has held in Coca-Cola for more than two decades.

Buffett may like round numbers—and 700 million could be just the right figure for Bank of America.

This stylish family home combines a classic palette and finishes with a flexible floorplan

Just 55 minutes from Sydney, make this your creative getaway located in the majestic Hawkesbury region.