As Greedflation Starts to Fade, Wageflation Creeps In

Softer demand, more supply and rising labor costs all take the air out of profit margins

When inflation took off in 2021 in the U.S., so did corporate profits, leading to accusations of “greedflation” and calls in some corners for price controls. This year, Europe is going through the same debate amid soaring food prices.

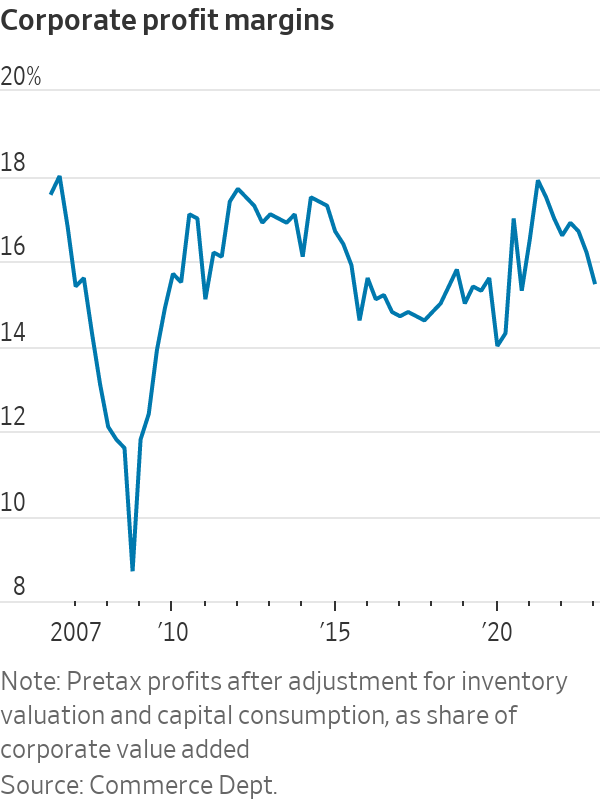

Judging by recent developments, inflation driven by corporations flexing their power to jack up prices more than costs—greedflation, as some called it—is on its way out. Pretax margins, which widened sharply in 2021 and 2022, were roughly back to pre pandemic levels in the first quarter of 2023, according to revised government data released last week. Margins in six of the S&P 500’s 11 sectors were lower in the second quarter than four years earlier, according to FactSet.

Narrowing profit margins, though, doesn’t necessarily mean an end to inflation. Wages are now growing faster than prices. While that doesn’t provoke the same outrage as soaring profits, it’s just as problematic for getting inflation down.

The circumstances of 2021 and 2022 made for a seller’s paradise. As the economy reopened, newly vaccinated consumers rushed to spend pent-up savings and stimulus cash. That demand collided with supply held down by pandemic disruptions and the inability of meeting so much demand with existing capacity.

The result: pretax margins shot from 15.6% in the fourth quarter of 2019 to 17.9% in the second quarter of 2021. That’s based on the Commerce Department’s measure of total value added by corporate businesses. This measure separates total costs into labor, profits, and non labour costs such as depreciation, interest and excise taxes, while excluding inputs, such as energy.

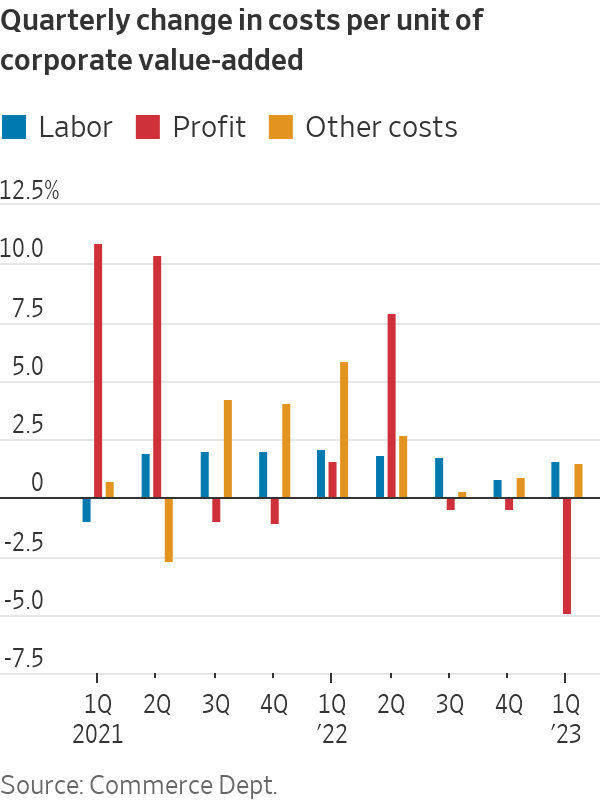

In the year through the second quarter of 2021, those companies’ prices rose 4.3%. At the same time, the cost of labour per unit of output fell 2.3%, because though wages were rising in that time, output per worker (productivity) was rising faster. Profit per unit of output rose a whopping 40%.

Greedflation is a catchy phrase, but not of much analytical value. Businesses always set prices to maximise profits. Raising them too much risks competitors ramping up supply to take market share.

But in 2021 and most of 2022 many companies couldn’t expand supply because of shortages of materials, labour or transport capacity. In the past when demand for vehicles rose, manufacturers effortlessly boosted output. This time, a shortage of semiconductors curtailed production and manufacturers responded to strong demand by slashing incentives and raising prices. General Motors sold fewer vehicles in both 2021 and 2022 than in 2019 but in both years made about 50% more profit. Companies weren’t the only beneficiaries: so was anyone with a used car to sell.

While greed is timeless, companies conceivably may have more power to translate greed into prices because of declining competition. The Biden administration, for example, blamed soaring meat prices in part on consolidation among meatpackers. But that wouldn’t have translated into such high prices without so much demand from locked-down consumers and the industry enduring production interruptions and labour shortages due to Covid-19, drought, avian flu and shrunken herds.

In recent quarters demand has softened. Adjusted for inflation, consumer spending was flat in three of the past four months. Tyson Foods lost money in the second quarter as soft demand pulled down prices for pork and beef while feed and labour expenses rose.

Supply, meanwhile, seems to be improving, at least for goods. In a report this week, economists at Goldman Sachs said global shipments of automotive semiconductor chips and U.S. auto production in the past few months are finally above pre pandemic levels. As a result, automotive inventories and incentives are both on the rise. In May the average new car buyer paid $410 below sticker price, compared with $637 above a year earlier, according to Cox Automotive.

Demand for services is holding up better than for goods, and services supply is still constrained, in particular by labour shortages. One reason air travel is so expensive is that airline capacity this year is about 14% below pre pandemic trend levels, Delta Air Lines recently told shareholders.

As airlines add flights they stretch staff, aircraft and air-traffic controllers to capacity, leaving them vulnerable to the slightest disruption. After thunderstorms triggered hundreds of flight cancellations in recent weeks, United Airlines said it might reduce flights out of its Newark, N.J. hub to create a buffer.

Airlines also reflect a broader reality: Whatever pricing power business still commands is increasingly eaten up by labor costs. Pilot shortages caused by pandemic retirements have given unions bargaining leverage, with many seeking to replicate a 34%, four-year increase Delta gave its pilots this year.

Workers are slowly recapturing more of the economic pie. In the first quarter of 2023, wages and salaries rose to 49.3% of corporate value added, higher than in 2019. Labor costs per unit of sales rose 6% in the year through the first quarter, ahead of prices, which were up 5.3% in the same period. Profits per unit of output rose just 1.6%.

The trend of wages rising faster than prices has continued in recent months. That’s welcome relief for workers but poses a set of difficult tradeoffs: Either profit margins will have to narrow further, which businesses will resist; high inflation will have to continue, which the Federal Reserve is fighting; or productivity will have to boom, of which there is no sign yet. If none of those things happen, then wageflation, like greedflation, will have to go away.

Copyright 2020, Dow Jones & Company, Inc. All Rights Reserved Worldwide. LEARN MORE

Copyright 2020, Dow Jones & Company, Inc. All Rights Reserved Worldwide. LEARN MORE

This stylish family home combines a classic palette and finishes with a flexible floorplan

Just 55 minutes from Sydney, make this your creative getaway located in the majestic Hawkesbury region.

Continued stagflation and cost of living pressures are causing couples to think twice about starting a family, new data has revealed, with long term impacts expected

Australia is in the midst of a ‘baby recession’ with preliminary estimates showing the number of births in 2023 fell by more than four percent to the lowest level since 2006, according to KPMG. The consultancy firm says this reflects the impact of cost-of-living pressures on the feasibility of younger Australians starting a family.

KPMG estimates that 289,100 babies were born in 2023. This compares to 300,684 babies in 2022 and 309,996 in 2021, according to the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS). KPMG urban economist Terry Rawnsley said weak economic growth often leads to a reduced number of births. In 2023, ABS data shows gross domestic product (GDP) fell to 1.5 percent. Despite the population growing by 2.5 percent in 2023, GDP on a per capita basis went into negative territory, down one percent over the 12 months.

“Birth rates provide insight into long-term population growth as well as the current confidence of Australian families,” said Mr Rawnsley. “We haven’t seen such a sharp drop in births in Australia since the period of economic stagflation in the 1970s, which coincided with the initial widespread adoption of the contraceptive pill.”

Mr Rawnsley said many Australian couples delayed starting a family while the pandemic played out in 2020. The number of births fell from 305,832 in 2019 to 294,369 in 2020. Then in 2021, strong employment and vast amounts of stimulus money, along with high household savings due to lockdowns, gave couples better financial means to have a baby. This led to a rebound in births.

However, the re-opening of the global economy in 2022 led to soaring inflation. By the start of 2023, the Australian consumer price index (CPI) had risen to its highest level since 1990 at 7.8 percent per annum. By that stage, the Reserve Bank had already commenced an aggressive rate-hiking strategy to fight inflation and had raised the cash rate every month between May and December 2022.

Five more rate hikes during 2023 put further pressure on couples with mortgages and put the brakes on family formation. “This combination of the pandemic and rapid economic changes explains the spike and subsequent sharp decline in birth rates we have observed over the past four years,” Mr Rawnsley said.

The impact of high costs of living on couples’ decision to have a baby is highlighted in births data for the capital cities. KPMG estimates there were 60,860 births in Sydney in 2023, down 8.6 percent from 2019. There were 56,270 births in Melbourne, down 7.3 percent. In Perth, there were 25,020 births, down 6 percent, while in Brisbane there were 30,250 births, down 4.3 percent. Canberra was the only capital city where there was no fall in the number of births in 2023 compared to 2019.

“CPI growth in Canberra has been slightly subdued compared to that in other major cities, and the economic outlook has remained strong,” Mr Rawnsley said. “This means families have not been hurting as much as those in other capital cities, and in turn, we’ve seen a stabilisation of births in the ACT.”

This stylish family home combines a classic palette and finishes with a flexible floorplan

Just 55 minutes from Sydney, make this your creative getaway located in the majestic Hawkesbury region.