Big Tech Stops Doing Stupid Stuff

This year it might be smart to invest in companies that think a little smaller

The era of moonshots is (mostly) over. This year tech companies are taking a more earthly approach.

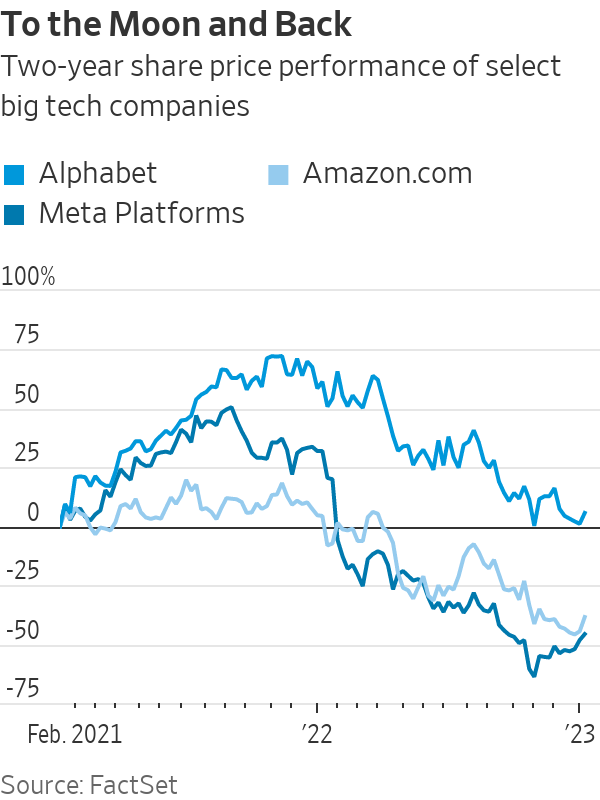

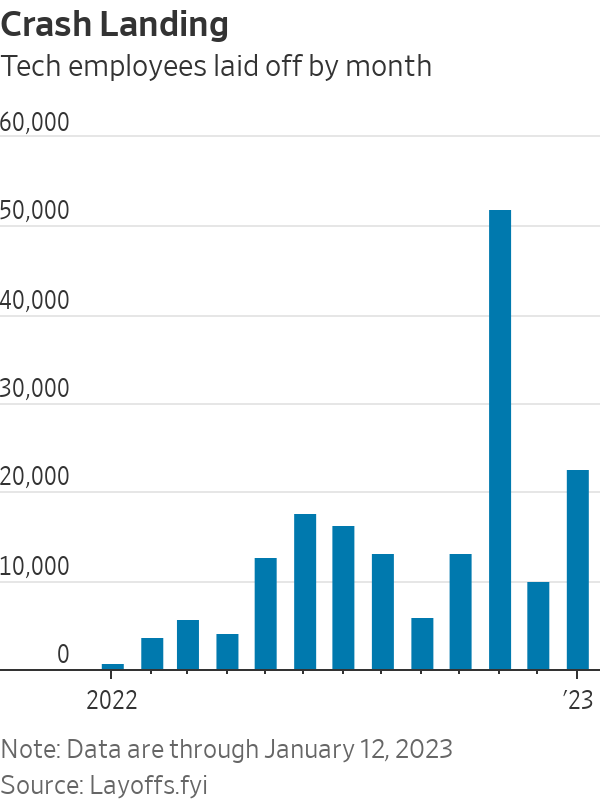

Stock charts both explain the change in boardroom sentiment and tell the story following an epic Covid-fuelled rise and fall. The tech-heavy Nasdaq fell 33% last year—its worst performance since 2008. Big tech, which spent the past several years spending on big dreams, is starting to think smaller. Last year more than 1,000 tech companies laid off employees, resulting in over 150,000 lost jobs, a tally by layoffs.fyi shows. It is an eye- popping number that could actually get worse: More than 23,000 tech workers have already been let go this year as of Jan. 13, the same tracker shows.

Many of these workers were newly hired under the mistaken assumption that booming pandemic demand would become the new normal. But a good percentage were legacy employees working on projects that, given today’s market environment, range from fiscally irresponsible to projects that fall well outside their parent company’s wheelhouse.

Meta Platforms and Amazon.com are the most high-profile examples, having cut a combined 29,000 workers so far. Meta is still reeling from an online advertising slump and the many billions of dollars that Chief Executive Officer Mark Zuckerberg is throwing at a new virtual world dubbed the metaverse. Amazon is coping with a retail slowdown in part by scaling back spending in unprofitable business areas such as its Alexa-controlled electronics products.

Meta Chief Technology Officer Andrew Bosworth said in an internal memo late last year that his company had “solved too many problems by adding headcount,” according to a recent newsletter published by the Verge. He reportedly added that headcount comes with overhead, which “makes everything slower.”

Despite its much-touted virtual ambitions, Meta said in a blog post last month that it is still devoting 80% of its total investment dollars to improving its own legacy business. In the Verge’s recent interview, Mr. Bosworth acknowledged that Meta is “changing our investment strategy” to the extent that some projects have to demonstrate value sooner to justify their high burn.

The ax also seems to be falling at the original moonshot factory: The Wall Street Journal reported that Google-parent Alphabet is laying off more than 200 employees at its Verily Life Sciences unit, plus another 40 at its robotics software company, Intrinsic. Both are part of Alphabet’s Other Bets segment, which racked up $5.9 billion in operating losses over the past four quarters while generating barely $1 billion in revenue.

Those cuts are unlikely to be the last at the Google parent, which added more than 30,000 new employees in the first nine months of 2022, even as its own advertising business started slowing.

Smaller tech companies are feeling the burn too. Redfin CEO Glenn Kelman told the Journal recently that if he could jump back in time 18 months, he would advise companies looking for profits to just “stop doing stupid stuff.”

He speaks from experience: The real-estate brokerage laid off 13% of its staff and shut down its automated home-flipping business late last year after deeming the operation too risky and expensive to continue. That followed a second quarter in which its so-called iBuying business had swelled to account for over 40% of its overall revenue. Channeling an old playbook for the new year, Mr. Kelman said in his company’s third-quarter report that Redfin “will have more cash and sell more properties” by focusing on its online audience and on better brokerage services.

Competitor Zillow gave up on its own iBuying business a year earlier than Redfin for similar reasons. It has since refocused on finding better ways to help its customers buy and sell other people’s homes. It is now using artificial intelligence to do such things as helping apartment hunters view available listings on New York City buildings they pass by and helping sellers generate floor plans for online listings based on photos. Zillow is also bundling its technology into an updated product to bolster traditional agents’ businesses.

A sector that has long worked to disrupt is now focusing on enhancing what already exists. In ride-share, Uber Technologies has now added taxi bookings to its platform in many cities, essentially feeding business to a competitor (but not without taking a small cut, of course). In Britain, Uber users can also book trains, buses and rental cars through its app. With Uber Explore, users across several cities can even book restaurant reservations and experiences.

Reinventing the wheel is so last year. The best tech investments of 2023 might be companies content to spend their coin greasing it.

Copyright 2020, Dow Jones & Company, Inc. All Rights Reserved Worldwide. LEARN MORE

Copyright 2020, Dow Jones & Company, Inc. All Rights Reserved Worldwide. LEARN MORE

This stylish family home combines a classic palette and finishes with a flexible floorplan

Just 55 minutes from Sydney, make this your creative getaway located in the majestic Hawkesbury region.

Continued stagflation and cost of living pressures are causing couples to think twice about starting a family, new data has revealed, with long term impacts expected

Australia is in the midst of a ‘baby recession’ with preliminary estimates showing the number of births in 2023 fell by more than four percent to the lowest level since 2006, according to KPMG. The consultancy firm says this reflects the impact of cost-of-living pressures on the feasibility of younger Australians starting a family.

KPMG estimates that 289,100 babies were born in 2023. This compares to 300,684 babies in 2022 and 309,996 in 2021, according to the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS). KPMG urban economist Terry Rawnsley said weak economic growth often leads to a reduced number of births. In 2023, ABS data shows gross domestic product (GDP) fell to 1.5 percent. Despite the population growing by 2.5 percent in 2023, GDP on a per capita basis went into negative territory, down one percent over the 12 months.

“Birth rates provide insight into long-term population growth as well as the current confidence of Australian families,” said Mr Rawnsley. “We haven’t seen such a sharp drop in births in Australia since the period of economic stagflation in the 1970s, which coincided with the initial widespread adoption of the contraceptive pill.”

Mr Rawnsley said many Australian couples delayed starting a family while the pandemic played out in 2020. The number of births fell from 305,832 in 2019 to 294,369 in 2020. Then in 2021, strong employment and vast amounts of stimulus money, along with high household savings due to lockdowns, gave couples better financial means to have a baby. This led to a rebound in births.

However, the re-opening of the global economy in 2022 led to soaring inflation. By the start of 2023, the Australian consumer price index (CPI) had risen to its highest level since 1990 at 7.8 percent per annum. By that stage, the Reserve Bank had already commenced an aggressive rate-hiking strategy to fight inflation and had raised the cash rate every month between May and December 2022.

Five more rate hikes during 2023 put further pressure on couples with mortgages and put the brakes on family formation. “This combination of the pandemic and rapid economic changes explains the spike and subsequent sharp decline in birth rates we have observed over the past four years,” Mr Rawnsley said.

The impact of high costs of living on couples’ decision to have a baby is highlighted in births data for the capital cities. KPMG estimates there were 60,860 births in Sydney in 2023, down 8.6 percent from 2019. There were 56,270 births in Melbourne, down 7.3 percent. In Perth, there were 25,020 births, down 6 percent, while in Brisbane there were 30,250 births, down 4.3 percent. Canberra was the only capital city where there was no fall in the number of births in 2023 compared to 2019.

“CPI growth in Canberra has been slightly subdued compared to that in other major cities, and the economic outlook has remained strong,” Mr Rawnsley said. “This means families have not been hurting as much as those in other capital cities, and in turn, we’ve seen a stabilisation of births in the ACT.”

This stylish family home combines a classic palette and finishes with a flexible floorplan

Just 55 minutes from Sydney, make this your creative getaway located in the majestic Hawkesbury region.